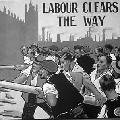

The British Labour Party was formed over 100 years ago to provide an independent political voice for working-class people. Ed Doveton describes this struggle, which is paralleled by today’s campaign for a new mass workers’ party. First published in Socialism Today

THE LABOUR PARTY was founded in 1900, first as the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) then as Labour Party in 1906. It emerged as a broad-based organisation reflecting the diverse range of existing organisations already developed by working people under capitalism. It encompassed the varied working-class political trends: the newly organised, militant, unskilled workers; the more traditional skilled workers; those involved in the co-operative movement; and others focused on issues such as education. Within its ranks were socialists, Marxists and reformists, such as those in the Fabian Society. The Labour Party in that sense became an arena within which the political arguments for socialism, and the differing policies and tactics to achieve it, were debated. It was seen by the working class as a tool with which it could fight for change, as a class.

A long period of struggle had preceded the foundation of the Labour Party, centred on the idea of establishing independent political representation of the working class, separate from the existing capitalist parties. In the 1890s, the major obstacles to the new workers’ party were two-fold. Firstly, the organisational support given by the traditional trade unions to the Liberal Party. Secondly, the mass electoral support for the Liberals and Tories by those working class men who did have the vote.

In an ironic twist of history, the situation in the 1890s has similarities 100 years later in our present day politics. Once again, socialists and class-conscious trade unionists have begun struggling for the creation of a new workers’ party. This time, however, the major obstacle is not from the Liberal Party but from New Labour. This party has become a clone of the capitalist parties it was set up to replace!

In the 1890s, the major trade unions saw the Liberal Party as the political party which would best represent their interests, although the unions were not formally affiliated to it. National and local union officials were often Liberal Party members and were wined and dined by the Liberal hierarchy. Trade unionists would put forward a version of Liberal ideology: that the economy of ‘the country’ was important and that the interests of capital and labour could often be the same.

This attachment of trade union officialdom to the Liberal Party began 40 years earlier in 1867, during the culmination of a mass working-class movement demanding the right to vote. The years 1866 and 1867 had witnessed large demonstrations all over the country and a mass rally in London which ended with a riot in Hyde Park. The establishment parties were fearful of a growing mood that hinted at revolution. To stem the tide, they quickly passed legislation giving the vote to millions of urban working-class males. The victory was incomplete, not least the exclusion of women and rural workers. But, in the ensuing general election, the Liberal Party moved quickly to absorb the trade union leadership in a successful attempt to capture sections of the new working-class voters.

The Liberal grip

THROUGHOUT THE following three decades the links between the unions and the Liberal Party remained solid. Over this period, the Liberals were seen by many as the ‘natural party’ for the working class. Some workers became Liberal councillors and in mining areas, where the working class vote was overwhelming, trade unionists actually became Liberal MPs (becoming known as the Lib-Lab MPs). Trade union leaders would argue that their relationship with the Liberal Party was beneficial, and would point to minor pieces of legislation, passed by Liberal governments, that helped the working class or the trade unions directly. The term used by these working-class Liberals was ‘labour representation’. This concept was expressed year after year during the 1880s and early 1890s at the TUC annual conference, as the TUC parliamentary committee reported on its work with the Liberal establishment.

Within this convivial partnership there were constant tensions. A relationship between a capitalist party like the Liberals and the working class is full of contradictions. When it came down to a direct decision about favouring profits and capitalism against working-class interests, it was always the former which was supported. Often employers headed the local Liberal Party establishment or, at a national level, the Liberal Party would simply ignore calls for more deep-seated reforms, such as the demand for the eight-hour day. The antagonism was also expressed in an attempt by the Liberal Party to keep out the undesirable working class from representing the party as councillors or MPs, not dissimilar to the control on these positions by the contemporary New Labour machine, which regards socialists as an alien species which should not belong to the party.

Some of these tensions would eventually spread into TUC conferences. As early as 1887, the president opened the conference by arguing: "One thing is certain, this labour movement is the inevitable outcome of the present condition of capital and labour; and seeing that capital has used its position in the House of Commons so effectively for its own ends, is it not the strongest policy of labour now that it has voting strength to improve its surroundings?" This speech set the tone of a debate to set up a new workers’ party headed by the then young delegate, Kier Hardie, representing the Ayrshire miners in Scotland. But the idea was soon squashed by a series of delegates, who were Liberal Party members. They put forward the argument, often repeated, that a new party would split the Liberal vote and let the Tories in. The voters were not ready for a new party of labour and it would be much better to keep with the Liberal Party. Hardie was ferociously attacked by the Liberal MP, C Fenwick (delegate of the Northumberland miners), because he dared raise the anti-working class record of a Liberal parliamentary candidate recently supported by leading Liberal trade unionists at a by-election in Northwich.

The striking turning point

A CHANGE CAME in 1889, in what would later be seen as a turning point. This was the victory of newly organised trade unionists in the gas workers’ dispute, leading to the formation of the National Union of Gasworkers and General Labours. Later that same year came the London dock strike, which also saw the setting up of a new union. These disputes brought previously unorganised workers into the trade union movement, led by men who were socialists and who supported the demand for a new workers’ party.

By the 1893 TUC conference, one of these leaders, Ben Tillett, was moving a motion for a separate fund to support independent labour candidates and an elected committee to administer these funds. It included a worked out process to select candidates who pledged to support the policies of the trade unions. James MacDonald, later an early leader of the Labour Party, put forward an amendment, (passed by 137 votes to 97) calling for all such candidates to "support the principle of collective ownership and control of all the means of production and distribution". It was the first move in the creation of what would eventually become the Labour Party. But, in the manoeuvrings of the conference, Liberal Party members ensured that this resolution became a dead letter. This was signalled in the defeat of a further resolution by Hardie calling on labour members of parliament to sit in opposition to the Liberals.

Over the next few years, socialists and militant trade unionists attempted to put flesh on the bones of this resolution, while Liberal trade unionists attempted to block its effectiveness. A critical issue centred on finance. The Liberal Party trade unionists prevented the funds of the unions they controlled from being used to support working-class candidates standing independently of the Liberal Party. Unlike today, when MPs make themselves rich by gaining a parliamentary seat, being an MP was a non-paying job. Only the rich could afford to sit in parliament. So it was necessary for trade unions to find the money for the election campaign and to pay a salary should the candidate be elected. By blocking funds, the Liberal trade unionists could hold up the creation of a new workers’ party.

Equally, the Liberals curtailed further debate on this issue in the TUC, defeating resolutions and proposals at the 1894, 1895 and 1896 congresses. In 1895, the congress president, councillor Jenkins, a Liberal president of Cardiff trades council and a delegate from the Shipwrights’ Society, used his opening speech to carry out a full frontal attack on the Independent Labour Party (ILP) for standing candidates in the 1895 general election. He even attempted a slur that, because independent labour candidates undermined Liberal Party votes, the ILP was funded by the Tories.

Catalysts of change

BUT THE TIDE of history was about to turn against the Liberals. Conflict between labour and capital was intensifying as the economic upturn of the early 1890s took a dip towards the end of the decade. Additionally, British manufactures were experiencing sharpened competition from the expanding economies of the USA and Germany. As a squeeze on profits developed the bosses turned to reduce wages and attack the power of the trade union movement to defend its members’ interests. Although the Tories were in power, having won the 1895 and 1900 general elections, the Liberal Party was reluctant to commit itself to reversing the attacks on the labour movement. Many Liberal Party members were also employers, the very people carrying out some of these attacks.

At the same time, throughout the 1890s in one local area after another, small but determined groups of socialists were beginning to influence the organised movement, enabling them to replace Liberal trade unionists with socialist representatives in a few places. This activity by socialists on the ground, combined with the numerical growth of the new unions such as the gasworkers and dockers, helped to transform the situation. This process, alongside the alienation of some of the more traditional unions from the Liberal Party in the late 1890s, began shifting the ground of support within the TUC.

The eventual formation of what would become the Labour Party was not automatic. There was a dialectical relationship between the general economic forces creating conflict between labour and capital, the old and new unions, and the conscious intervention of socialists acting as a catalyst of change. As the famous phrase of Karl Marx states, "man makes his own history, although not in circumstances of his own choosing". But within this it is necessary that man does indeed ‘make his own history’.

Historians often cite two legal judgments as being critical in the development of the Labour Party: Taff Vale (1900-01), and Osborne (1909). Both were strident attacks on trade unions. In reality, these judgments rapidly increased a trend which was already underway, rather than sparked the creation of the Labour Party itself. Setting up the LRC had been agreed a year before the Taff Vale judgment, at the 1899 TUC conference. This laid the foundation for what would become the Labour Party, and brought to an end the period of the pre-birth of the new workers’ party.

The next two decades would see the growth and spread of the new party in working-class communities, reflected in unions, local councils and, increasingly, parliamentary seats. But, as with the previous decade, success would not be automatic. The working-class voter was still wedded to the habits of the past and remained attached to the capitalist Liberal Party. Many of the old Liberal trade unionists were still influential and continued to claim that the Liberal Party was the party for workers. They cited as evidence the fact that large numbers of workers still voted Liberal, mistaking voting habits for a zodiac sign determining the character of the party.

Looking back at this history of the Liberal Party, which by its policies and ideology supported the interests of capitalism, we might wonder how little has changed today. The New Labour government and Labour-controlled councils act like ruthless employers, affecting millions of public-sector workers, who have endured low pay, effective pay cuts through below inflation pay awards, alongside real and threatened job losses. Labour stands by as employers close down businesses and sack workers. At the same time, the government gives away billions of pounds to prop up the banks. Its stated intent is restoring the profits of firms while demanding that the working class picks up the bill. It is this context that poses once again the need for a party which can represent the interests of working-class people. Conscious socialists should be fighting to achieve this objective.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Be the first to comment