How 18 million people brought down Thatcher

The different outcomes of these two titanic battles came down to the character of their leaderships, and the differing strategies and tactics, as well as organisation, which were deployed. In the first, the trade union leadership mobilised the legions of the trade movement in the epic nine days of the general strike. Victory was in the grasp of the working class; its overwhelming power was displayed and yet defeat ensued. There was no such mobilisation of trade union power or of real, official involvement in the poll tax struggle by the trade unions. Ironically, it was for this very reason – the absence of leadership from, indeed outright sabotage by, the official Labour and trade union tops with Kinnock at their head – that this struggle was victorious.

It remains an incontestable historical fact that it was neither the official leadership of the labour movement nor small left groups – without a feel for the real pulse and movement of the working class – that provided the leadership for the decisive poll tax victory. It was, instead, the vilified and persecuted forces of genuine Marxism gathered around the newspaper ‘Militant’ which played the crucial role.

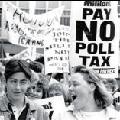

The Battle to defeat the poll tax, photo Steve Gardiner

The battle of Liverpool City Council

This battle had been prepared by the whole preceding period, which had seen both sides testing out their forces in struggle, particularly in the Liverpool campaign of 1983-87. The poll tax victory would not have been possible without the events in Liverpool, an important dress rehearsal for the clash over the poll tax. Liverpool City Council, backed by a mass movement, including city-wide general strikes of public-sector workers, first of all humbled then defeated Thatcher, forcing her to retreat and grant concessions in 1984. This was at a time when numerous other councils, claiming to stand on the ‘left’, were joined in common struggle with Liverpool. However, these former ‘left’ leaders of Labour councils such as Ken Livingstone and David Blunkett eventually capitulated, leaving Liverpool and Lambeth councils isolated by the summer of 1985. Nevertheless, the heroic Liverpool struggle was lodged in the consciousness of particularly the most politically aware sections of the labour movement and the working class. Eric Heffer, the late left-wing Labour MP for Liverpool Walton, in a favourable review of our book, ‘Liverpool: The City that Dared to Fight’, that sums up the experiences of the struggle, wrote: “It [the Liverpool struggle] was ‘politics put to the test’ and contrary to what some would say, it was a test that the Liverpool councillors and party members passed”. [Militant 884, 19 February 1988.]

At the launch of this book in London. I commented on its relevance to the forthcoming struggle on the poll tax: “The vast majority [of British people] are opposed to the tax, but the Labour leaders have made it clear that the struggle is to be restricted to parliament. But the history of this government is that they do not listen to parliamentary speeches. Only when a mass struggle is mobilised, as it was in Liverpool, can the labour movement force the ‘Iron Lady’ to retreat. Scottish councils [where the poll tax was introduced a year earlier than England and Wales] have the same choice as in Liverpool. Either they can get the odium of implementing the poll tax or, like Liverpool, say ’no’, refuse to collect it and call a one-day general strike. Otherwise, they might as well resign their positions. There is an explosive situation developing on the housing estates. The government has made a big error.” [Militant 883, 12 February 1988.]

The Battle to defeat the Poll Tax, photo by Phil Maxwell

Thatcher’s big mistake

We recognised right from the outset that Thatcher had made a fundamental mistake. She had abandoned her ‘salami tactics’ of taking on one section of the labour movement while seeking to mollify others, shown in the Tory government’s tactics used against the miners, the print workers at Wapping and, of course, against Liverpool. This time, she had decided to take on the vast majority of the British people all at once, so to speak. One month after the Tory general election victory of 1987, Militant carried a front-page headline on 7 July: ‘Tory Poll Tax Robbery’. One result of the 1987 election was to reduce the Scottish Tory representation at Westminster so that all their MPs could get into two taxis! Thatcher planned her revenge by introducing the poll tax first of all in Scotland. We pointed out in our newspaper: “The Thatcher family in Dulwich will save £2,300 per year… an average family in Suffolk will pay an extra £640.”

But our response was not just on the level of propaganda; we actively prepared above all in Scotland, where the poll tax was first introduced. Thatcher boasted at this stage the poll tax was to be the “flagship” of her government. We wrote in Militant [29 July 1988]: “The Titanic was the ‘flagship’ of the British Merchant Navy and considered unsinkable until it hit an Atlantic iceberg! Now the Tories are on a collision course with a far more formidable obstacle – the embittered and mobilised Scottish working class, and only just behind them their English and Welsh counterparts! With clear leadership the labour movement can sink the Tory flagship without trace. When the flagship goes down, the Admiral either goes down with it or is sacked.”

The battle to defeat the Poll Tax, photo by Dave Sinclair

These prophetic words were to be borne out four years later. With the poll tax, Thatcher achieved what the Labour and trade union leaders had failed to do in the previous nine years: she had united and generalised the struggles of the working class against her government. Previously, she had been very careful not to take on the whole of the working class or to open up an offensive on two fronts. But the poll tax affected young and old, employed and unemployed, the sick and disabled, council tenants and house owners, as well as the black and Asian populations. All except the rich and upper middle class were to be hit by the poll tax.

Equally, the fatal error that she and her ministers made was to mistake the supine position of the Labour leaders for an accurate reflection of the mood on the ground. We were still wedded to the idea, at this stage, that the official labour movement could be won over to take effective action against the poll tax. This was despite the vicious witch-hunt that had been launched against Militant’s leading figures – the five members of the Editorial Board had been expelled from the Labour Party in 1983 – and the persecution of the Liverpool Militants from 1985 onwards, both by the Labour leadership and the state. We had also not abandoned hope that the struggles of the working class would act to transform the Labour Party in a leftward direction. It has to be admitted that even at this stage of the late 1980s, this hope was misplaced. The scorched earth policy of Labour’s right – orchestrated by Kinnock’s local apparatchik in Liverpool and ‘flame thrower’ Peter Kilfoyle – demonstrated that Labour was, in fact, irredeemable at that stage. (New Labour subsequently moved so far to the right that, merely by standing still, Kilfoyle has been transformed into a ‘left’ today!)

It would have been better – as some of us suggested at the time – for Militant to have launched an independent organisation in 1987, at the time of the witch-hunt in Liverpool, rather than five years later in Scotland. Politically, Militant would have been better prepared to benefit from its leadership of the poll tax struggle. Also, with the bigger numbers that such a stand would have resulted in, we would have been more able to withstand the hostile political gales resulting from the collapse of Stalinism and, with it, the planned economy in the 1990s. It seems incredible to recall now that at the very time when Marxists in particular, but also others on the left of the Labour Party, were seeking to harness the indignation of the poll tax to confront the government, the Labour leadership spent all its efforts expelling its most combative and prominent fighters. Tommy Sheridan – who headed the struggle in Scotland and was a well-known Militant supporter at the time – was expelled from the Labour Party, and later imprisoned, as was the heroic, late Terry Fields MP; Dave Nellist MP was ‘merely’ expelled, all for offering effective leadership to the most oppressed, who were worst effected by the imposition of the tax.

Can’t pay, won’t pay

Notwithstanding this persecution, Militant was unswerving in identifying the poll tax battle as the key struggle from 1987 onwards and drew all the necessary political and organisational inferences from this. The Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP), after initially dabbling in Glasgow in the first stirrings against the poll tax, effectively withdrew from the field of battle. Under the direction of its leader, the late Tony Cliff, it decided that the main demand of the poll tax movement from its inception – again under the influence of the suggestions of Militant, “Can’t pay, won’t pay” – was impractical: “The non-payment campaign does not exist. Not paying the poll tax is like getting on a bus and not paying your fare; all that will happen is you’ll get thrown off”! [Tony Cliff in a speech to Newcastle Polytechnic Socialist Worker Student Society, May 1989, quoted by Peter Taaffe, Socialism and Left Unity, p16.] They were only repeating their mistaken stance during the miners’ strike where they concluded early that it was “unwinnable” because of an alleged “downturn” in the class struggle! By the time of the Liverpool battle, they had become downright hostile to Militant and its leadership role in crucial struggles. Their infamous front-page headline from Socialist Worker “Sold down the Mersey” was their way of greeting the victory of the Liverpool workers. This contrasted starkly with the widely recognised view in the city and nationally throughout the labour movement that Thatcher had suffered a severe setback. As an organisation, the SWP played no central role in the poll tax struggle other than later claiming, usually out of earshot of Militant supporters, that they were, in fact, leaders of this battle! Individual members of their party and others did participate – some even being fined or imprisoned – but this was a tiny minority of their forces.

They also claimed that the so-called ‘Trafalgar Square riot’ – which we will comment on later – was decisive in defeating the poll tax. In this, they were at one with right-wing capitalist commentators who covered up the crucial importance of the non-payment campaign. Important though the ‘riot’ was, it was more symptomatic of the mood against the tax that existed. It was mass non-payment, suggested and organised by Militant and its allies, which was the real reason that compelled Thatcher and her successors to retreat and ditch the tax. Similarly, anarchist groups, who occasionally latched onto and viciously attacked the organised anti-poll tax movement, if it had been left to them would not have defeated Thatcher. The poll tax struggle was objectively determined by the character of the all-embracing attack of Thatcher on the vast majority of the working class and even the British people as a whole.

Superficial capitalist commentators see mass resistance arising from the ‘fiendish plotting’ of a handful of ‘agitators’. This is the view of the historian Robert Service, for instance, and others in ascribing ‘conspiratorial’ methods to the Bolsheviks in the October 1917 revolution in Russia and the role of revolutionaries in general in all revolutions! William Shakespeare, through Owen Glendower in Henry the Fourth Part One, can declare: “I can call spirits from the vasty deep.” Hotspur replies: “Why, so can I, or so can any man; But will they come when you do call for them?” The mere incantation of ‘revolution’ will not result in its materialisation.

Revolution and counter-revolution for that matter are only possible when the underlying developments have prepared the preconditions for the social eruptions characterised by such an event. Even then, it can only come to fruition – as the history of both the successful socialist overturn in Russia and their defeat elsewhere demonstrate – if the movement possesses the organisation, the necessary leadership and clear objectives – strategy and tactics – to ensure victory. The poll tax did represent an element, at least, of ‘revolution’ in the sense of a mass movement – one of the greatest in history, certainly in Britain – which effectively overturned the government and underlined the power of the masses once they move into action. Struggle was inevitable given the character and the scale of the attacks. The choice, however, was between an organised mass struggle as a means of ensuring victory or an inchoate scattered movement from below with less chance of defeating the government.

A similar dilemma confronts the working class and the labour movement today on the issue of the unprecedented attacks being prepared to slash public expenditure. The main political parties in Britain – whoever wins the next general election – will seek to slash the £200 billion government deficit through savage cuts in jobs, services and the pay of public sector workers. There will inevitably be resistance to the cuts that are being proposed. But the same dilemma confronts this upcoming struggle as the poll tax battle 20 years ago.

Scotland takes the lead

Everyone seemed to be opposed to the poll tax. Many even initially embraced the demand “Can’t pay, won’t pay”, including some sections of the ‘official’ movement – the trade unions, Labour MPs, etc. But once there was a question of proceeding from words to deeds then one by one these forces peeled away. Even ‘left’ Labour MPs refused to join millions in not paying the tax. This undoubtedly initially discouraged some workers from struggling. At the outset of the battle there was indignation at the tax but little confidence that Thatcher could be stopped. Campaigners were met on the streets with the refrain: “She [Thatcher] defeated General Galtieri in the Falklands War, crushed the miners and the printers. What chance have you got of defeating this tax?” These ideas were countered with facts, figures and arguments. But sometimes the “propaganda of the deed” is needed –not in the anarchist/terrorist sense of terroristic action against individual capitalists – but of mass action. It was necessary to demonstrate the colossal subterranean revolt brewing on this issue precisely through deeds and heroic deeds at that, particularly in Scotland first.

Singling out Scotland for implementation of the tax a year early was perceived by the mass of the Scottish people as a ‘colonial’ punishment for daring to defy her. Tory Secretary of State for Scotland Malcolm Rifkind, in relation to the Tory government’s power over Scotland, was widely quoted as invoking Hillaire Belloc’s poem: “Whatever happens we have got the Gatling gun and they have not.” He denied that he had said this but the Scottish people remained unconvinced, which reinforced their determination to oppose the tax. At that time, it was a kind of popular axiom that there were certain ‘don’t dos’ for governments. Never take on Mike Tyson (the seemingly invincible world heavyweight boxing champion of the time) and never take head on the Scottish working class!

It was Trotsky who remarked that in the veins of the British working class ran Scottish, Irish and Welsh blood, which gave it a revolutionary temper at critical moments in history. In other words, because of historical circumstances – suffering in the extreme at the hands of the British capitalists – revolutionary feeling was greater in Scotland, Ireland and Wales than it was, perhaps, in England. Even the police and civil guard of the notorious dictatorial regime of General Franco in Spain had received a first-hand lesson of what would result from ignoring this maxim. Used to beating up and attacking Spanish workers campaigning for their rights, the police decided to attack Glasgow Rangers supporters after a match in Madrid. This was one of their biggest mistakes. Unprecedented scenes unfolded with the police, after initially attacking the supporters and arousing their fury, forced to turn on their heels and beat a retreat!

Thatcher, however, ploughed on regardless. A labour movement campaign was launched in Edinburgh in December 1987 initiated by Militant supporters. Soon after this, steps were taken in the West of Scotland, particularly in areas like Pollok, where Tommy Sheridan lived himself at that stage. In particular, the organisation of anti-poll tax unions was undertaken which led to the idea, promoted by Militant, of a West of Scotland anti-poll tax federation. But before this step had been taken there had been serious discussions, both in Scotland and in the rest of Britain in Militant’s ranks, about the programme and organisational steps to be taken to maximise the greatest possible resistance to the poll tax. In April 1988, a one-day conference with delegates from every area of Scotland where Militant had support and influence was organised, attended by myself on behalf of the national leadership. This meeting clarified important tactical issues and gave the green light to Militant supporters in Scotland to concentrate on the poll tax as the key issue to link the struggle and the battle that was likely to develop on an all-British scale later. Militant summed up the situation in a centre-page article [29 July 1988]: “The Thatcher juggernaut is at the gates of Glasgow and Edinburgh. She intends to roll it over the ‘whitened bones’ of the Scottish labour movement and then trample over the English and Welsh working class.”

The April 1988 Scottish conference of Militant took the decision to organise anti-poll tax unions throughout Scotland to systematically press for a programme, the central demand of which would be “non-payment” of the tax. At each stage the fighting approach of Militant contrasted sharply with that of the leadership of the Scottish labour movement. There were, however, great hopes, because of the unpopularity of the measure, in persuading the movement, the trade unions and the Labour Party, to come in behind the struggle. One MP at the Labour Party conference in Scotland the month before had declared: “There is an army waiting to be led down the road of non-payment.” However, even then he could not resist comparing Neil Kinnock to “a general leading his troops into battle carrying a white flag”. [Militant, 888, 18 March 1988.]

On the day that this conference had opened, an opinion poll had showed that 42% of the Scottish people favoured an illegal non-payment campaign against the poll tax. Amongst Labour voters the figure was as high as 57%. Yet the speech to conference by Kinnock was so poor that the Glasgow Herald wrote that it was “universally rated as a disaster”. The conference voted two to one for a resolution opposing illegality. It was at total variance with the mood of the vast majority of delegates, particularly from the constituency parties. However, the trade union tops cast their block votes in favour of the party’s Scottish leadership. Even then it was decided to reconvene the conference in the autumn to reconsider the non-payment option.

This gave an opportunity to the advocates of non-payment to mobilise working people in action in favour of this demand. Consequently, massive meetings on Scottish housing estates showed that the workers expected the Labour leaders to take a lead. Tommy Sheridan was elected as secretary of the Pollok Anti-Poll Tax Union and reminded a mass meeting of the 47 Liverpool councillors who were prepared to stand firm and defy Tory law. “We need them here in Pollok,” was the audience’s response. [Militant 893, 22 April 1988.]

A defining moment in the campaign in Scotland was when Tommy Sheridan was addressing an anti-poll tax meeting and Michael, now Lord, Forsyth, then a Tory MP in Scotland, entered the fray. He was in ‘evening dress’, having come from a function in his constituency. Verbal exchanges took place, which were terminated when Tommy declared: “Tell your boss [Thatcher] we [pointing to the meeting] are going to defeat her tax, her and her government.” Forsyth, shaken, turned as white as a sheet but did not respond. However, he is back today calling for savage cuts in state spending. He should receive the same warning now as he did 21 years ago from the mass anti-poll tax movement!

In July 1988, 350 delegates representing thousands of workers in 105 anti-poll tax groups, mostly from community councils and tenants’ associations, agreed to set up the Strathclyde Anti-Poll Tax Federation. This conference called unanimously for a mass campaign of non-payment and for Labour councillors to refuse to pursue non-payers. It also called for the Scottish TUC to step up their campaign and organise a 24-hour general strike. Tommy Sheridan was elected unopposed as secretary of the Federation and promised vigorous leadership from the newly elected committee.

Even at the national Labour Party conference in October 1988, to the horror of the leadership, Militant supporters called for defiance of the poll tax. This came not just from Scotland but also from other parts of Britain. Alec Thraves, the delegate from Swansea, parodying Neil Kinnock’s infamous 1985 conference attack on Liverpool councillors, said that if Labour did not organise a successful campaign of non-payment “we will see the grotesque chaos of Labour councils, yes Labour councils, scuttling round in taxis handing out eviction notices to people who can’t afford the poll tax.” A Labour right-winger at this conference stated to a woman who could not afford to pay the tax: “If you can’t pay I am sure the courts will be lenient with you!”

Battle joined throughout Britain

In 1989, one million Scots were not paying the poll tax. Even the capitalist press like Scotland on Sunday had estimated that 800,000 Scots were not paying out of 3.9 million who should. This was indeed a very good mass demonstration of the ‘propaganda of the deed’! But not a whisper of this campaign appeared in the press outside of Scotland. By a thousand different channels, however, the information seeped through, particularly through leaflets and information supplied by the anti-poll tax unions. In answer to the above refrain about Thatcher being “unbeatable”, this was soon dispelled when campaigners informed them that a million had been organised not to pay the poll tax in Scotland. This campaign, even before it had reached the rest of Britain, had demonstrated the power of mass action, so long as it was organised and led by a leadership with a clear strategy and tactics. The rest of Britain would come to the aid of the poll tax battlers in Scotland, leaving the official trade union and Labour leaderships suspended in mid-air.

London supporters, mostly organised by Militant, raised the finances for a ‘Red Train’ to ‘speed to the front line’ in Scotland. Militant [24 March 1989] described the atmosphere: “‘The Anti-Poll Tax Express’, said Euston Station’s huge illuminated train information board… All 600 seats are taken – the train is packed. Many are school students, a good number of black youth; three women from an estate in Deptford who had decided to go just the night before; trade unionists and Young Socialists… singing and chanting lasts the whole journey: no chance of any sleep!… I can hear bagpipes. What’s the time? 4.20 am – we’re there! The piper passes the window flanked by two comrades with red flags. It’s our early morning call!… The Scottish comrades welcome us – we’re having a rally right here in the station.” There was a phenomenal turn out from Merseyside as 1,000 travelled from the area to this demonstration – repayment for the solidarity that Scotland had shown for their struggle. Twenty thousand took to streets of Glasgow against Thatcher’s iniquitous tax. The determination to defeat the poll tax was shown by a Welsh worker who gave up two tickets for the Wales v England rugby match: “The match is only for 80 minutes but the poll tax could last the rest of my life.” Weather-wise, it was a terrible day in Glasgow, with the rain lashing down from early morning till well after the demonstration finished.

This was followed by a massive demonstration in Manchester, nominally organised by the TUC, but effectively taken over by anti-poll tax demonstrators. The one million refusing to pay the tax in Scotland were used to prepare a colossal campaign in England and Wales. The first London demonstration of just 200 was organised in Waltham Forest, with even a contingent of Leyton Orient football fans marching against the tax. Lone voices in parliament such as Dave Nellist and Terry Fields sought to warn the government of what was coming. Dave declared in July 1989: “I give a clear warning to the Secretary of State that millions of people in England and Wales will not be able to pay the poll tax and that millions more will be unwilling to… Just under two years ago the Tory Reform Group described the poll tax as ‘fair only in the sense that the Black Death was fair, striking at young and old, rich and poor, employed and unemployed alike.’… That description was wrong in one basic respect. At least the rich catch the plague – the rich will not catch the poll tax.” [Militant 956, 11 August 1989.]

Crucial for the battle on an all-Britain scale was the organisation of the conference on 25 November 1989 of the All-Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation. Tommy Sheridan greeted 2,000 delegates to a body that was to play a decisive role in the history of the working-class movement and, indeed, in British history, as events the next year would demonstrate. There was much discussion in our ranks over what proposals would be best to put forward on the structure. Such was the decisive influence of Militant in the anti-poll tax unions that it would have been entirely possible for us to gain a ‘clean sweep’, and take all positions on the national committee. We decided against this, in order to give the movement as broad a base as possible, to facilitate the drawing in of all genuine forces who were prepared to struggle in action against the tax. Therefore it was agreed that we would pursue the policy of the united front by involving non-Militant supporters on the national committee. This was the case in Yorkshire, London and in the South West.

But still the Labour leadership resisted concrete action, centring all ‘their’ hopes – but not those of the working class – on a general election to kick out the Tories. One incident at the Labour Party conference in October 1989 indicated how far the Labour Party conference was from the mass of ordinary working-class people. Christine McVicar from Glasgow Shettleston Labour Party was seen by millions on TV news bulletins when she tore up her poll tax payment book at the conference rostrum. This was not just an individual gesture. She was moving a resolution calling for Labour to back the mass campaign of non-payment. She defiantly declared to the conference: “Without the Tolpuddle trade unionists and the Suffragettes breaking the law, we wouldn’t be here at this conference… I’m ripping up my poll tax book not as an individual but as part of a mass campaign of non-payment.” [Militant 964, 13 October 1989.] She was met with cheers from the socialist elements in the conference, and by jeers from right-wing Labour MPs and others. At this conference Militant was still able to attract 200 delegates to its public meeting – despite the mass expulsions. However, the right consolidated its hold in November with the removal of the last direct representative of the Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS) from its National Executive Committee, Hannah Sell. This then led to the winding up of the LPYS.

A prairie fire of protest

This was a dress rehearsal for the dramatic events of 1990. In history – at least as far as the pro-capitalist historians are concerned – 1989 and 1990, and subsequent years, were marked by the collapse of Stalinism and with it, unfortunately, the destruction of the remaining elements of the planned economy. This was then used, as we have consistently pointed out, to launch an ideological campaign, which allegedly ‘destroyed’ the ideas of socialism, struggle and solidarity – indeed, the very idea of the class struggle itself. But the real history of these years is not just that. In fact, 1990 was a tumultuous year of mass struggle and the early 1990s saw big public sector strikes in Belgium and elsewhere. With 1990 only weeks old, Militant [19 January 1990] carried the front-page headline “Smash the poll tax” with the call of the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation for “a mass demo on 31 March”. Thirty-five million people were to receive their poll tax bills in England and Wales on 1 April. The campaign was given a boost by the Tory Economist magazine which stated: “Imagine a country where more than one in ten of the adult population is refusing to pay a tax. Welcome to Scotland 1990.” In fact this organ of big business grossly underestimated the true level of non-payment in Scotland, which was as high as one in three in Glasgow alone. The Economist went on: “Today’s drama in Glasgow may be repeated tomorrow in Liverpool. How long before the Tories start to pine nostalgically for the much derided rates (previous form of local taxation Ed.)?”

The first months of the year saw a prairie fire of mass demonstrations sweep through formerly sleepy towns and villages in the south of England. Two thousand people denounced the Tory MP for Maidenhead as the “Ceausescu of Maidenhead” for supporting the tax. Debbie Clark and John Ewers wrote in Militant [2 March 1990] “It was like a scene from the Romanian Revolution – except this was taking place in the Gloucestershire town of Stroud.” In Hackney, 2,000 gathered outside the town hall. Hundreds lobbied Southwark council. 2,000 gathered outside Lambeth Town Hall, hundreds outside Waltham Forest and Haringey councils. Practically every area of the South was affected in one way or another by poll tax demonstrations and protests in February and March.

Militant was then identified by the capitalist press as the “enemy within” because of its splendid role in the poll tax struggle. Rupert Murdoch’s ‘Times’ and ‘Sun’ really plumbed the depths. The Sun compared us to football hooligans: “The Militant tendency is Labour’s own Inter-City Firm.” [Militant, 984, 16 March 1990.] To his eternal shame, Neil Kinnock repeated some of the wilder Tory claims. Tony Benn correctly concluded: “The Labour Party is more frightened of the anti-poll tax campaign than of the poll tax itself.” [Tony Benn, The End of an Era – Diaries 1980-1990, pp585-6.] Bristol, Norwich, Maidenhead, Weston-Super-Mare, Exeter, Gillingham and Birmingham saw demonstrations. However, this was all ascribed to professional protesters moving around Britain. Poll tax minister Chris Patten said they were all “rent-a-crowd outsiders, bussed in from Militant places like Stroud”! [Militant, 983, 9 March 1990.] But this did not convince all commentators. Robert Harris commented in the Sunday Times [11 March 1990]: “I doubt whether the ordinary voter, watching the violence on television, says: ‘Look at those horrible communists, Mabel. We must vote for Mrs Thatcher as the only person who can deliver us from these ruffians.’ The voter is more likely to say: ‘Look at the latest bloody mess that woman has landed us in.’” Harris was not to maintain this objectivity. He has evolved into a writer of best-selling fiction, but has accompanied this with uninformed spiteful attacks on Trotsky and Trotskyists in general. He recently compared Trotsky to an insufferable student: “Imagine the most obnoxious, middle-class student radical one has ever met – bitter, sneering, arrogant, selfish…”! [Sunday Times, 18 October 2009.] It takes one to know one! He was more accurate as a commentator 20 years ago than he is today.

Kinnock also condemned the advocates of mass non-payment of the poll tax as “Toy Town revolutionaries”, a phrase lifted from the Sun. In contrast, Tony Benn demanded an amnesty for all those who refused to pay. Kinnock condemned him as condoning “law breaking” with the clear implication that non-payers would be pursued through the courts by ‘Labour’ councils. But it was Labour MPs, even some on the ‘left’, who were not sufficiently resolute in supporting the millions who could not afford to pay, that were met with public hostility. Diane Abbott and Brian Sedgemore, Hackney’s two Labour MPs at the time, were confronted by a heckler in a public meeting: “We elected you and we can unelect you, unless you stand with us who are not paying.” [Militant 984, 16 March 1990.] A show of hands was called for and everyone in the room voted that they would not be paying with the exception of the two MPs on the platform!

The SWP had moved from lukewarm and passive support for the anti-poll tax campaign to opposition to the strategy of ‘non-payment’. Just prior to the 31 March demonstration, they declared in Socialist Worker [24 March 1990]: “The government calculates that a passive non-payment campaign can be whittled down eventually to a level it can manage… Activists should recognise a majority of workers are likely to feel they have no choice but to pay. Many will fear the consequences of court proceedings and falling into debt. Some will fear the loss of their jobs if they are fined.” Some commentators in the capitalist press were to the ‘left’ of the SWP. Victor Keegan wrote in the Guardian: “Judging by experience of Scotland and opinion polls in England and Wales the number refusing to pay will run into millions. Since enforcement on such a scale is impossible, this will not only bring the law into disrepute, but will generate a fresh backlash against the tax by those who are currently paying up.” [Militant, 986, 30 March 1990.] The SWP even argued that without the backing of the trade union leadership the campaign could not succeed!

The 31 March demo and Thatcher’s demise

This set the scene for the mass demonstrations of 31 March 1990. Scotland’s demonstration passed off peacefully, which was not the case in London. Responsibility for this has to be firmly placed on the shoulders of the government and the police. The demonstration became the lightning rod for all the discontented elements in society thirsting for revenge against Thatcher: the homeless, unemployed youth, the oppressed and destitute, miners as well as printers, and others who had felt Thatcher’s boot on their back. However, the march was completely peaceful, like a carnival at the outset. By the time the head of the march reached Trafalgar Square there had only been one arrest. The Square was soon full to its capacity and the back of the march had still to leave Kennington Park!

A handful of anarchists, joined by SWP members, were involved in clashes with the police but the overwhelming majority in what was then the biggest demonstration in British history (only since exceeded by the 2003 anti-war march) accepted the decision of the Federation for a huge but peaceful and democratic demonstration. The 31 March demonstration ‘riot’ was one of the most important events in labour history in the twentieth century. By itself it did not finish off the poll tax or Thatcher, as the SWP and others have claimed. The honour for fulfilling this belongs to the eventual 18 million-strong army of non-payers who were welded into an unbeatable force. But these mighty demonstrations were the visible and dramatic expression, both to the British ruling class and to the world, of the scale of opposition to the poll tax and the burning hatred of Thatcher and her government. It marked the beginning of the end of Thatcher herself. She declared in her memoirs: “For the first time a government had declared that anyone who could reasonably afford to do so should at least pay something towards the upkeep of facilities and the provision of the services from which they benefited. A whole class of people – an ‘underclass’ if you will – had been dragged back into the ranks of responsible society and asked to become not just dependants but citizens. The violent riots of 31 March in and around Trafalgar Square was their and the Left’s response. And the eventual abandonment of the charge represented one of the greatest victories for these people ever conceded by a Conservative Government.” [Margaret Thatcher: The Downing Street Years, page 661]

Following the actions of the police, who had deliberately provoked and attacked the demonstrators, Militant and the organisers of the demonstration were accused of being ‘anti-democratic’. Ultra-left sectarians and anarchists on the other wing accused Militant supporters of “collaborating with the police”. This was totally false. Tommy Sheridan and the other leaders were overwhelmingly re-elected to head the All-Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation. A nineteen-year old who had gone on a demonstration for the first time, more accurately reflected the mood: “I hope that in 20 years time I can look back and be proud to have been the child of world revolution and tell my children: ‘I was there, I saw it all happen, I saw Thatcher fall!’” [Militant 988, 13 April 1990.] He will still be waiting for the first part of his prediction to be borne out but Thatcher did indeed fall and it was not because of the TUC or the official Labour leadership. Four days after the epic mass demonstration, the TUC held a rally against the poll tax; in a hall holding 3,000 people, 800 were admitted, mostly union officials. The march to the hall was abandoned because only ten people turned out!

There could not have been a greater contrast between mass organisations and demonstrations led by Marxists and the impotence of the official trade union and Labour leadership. However, the 31 March demonstration alone did not compel the government or Thatcher to immediately retreat. It took a protracted non-payment campaign with 18 million people refusing to pay to achieve this. This was accompanied by some strikes, such as that of civil servants in Glasgow. The first flashpoint in the English poll tax courts came on the Isle of Wight. The court threw out 1,800 summonses for non-payment! Alison Hill concluded: “Based on this experience, I cannot see how successful court hearings can be held anywhere.” [Militant 996, 8 June 1990.] In effect, a protracted social ‘guerrilla’ campaign unfolded. The Guardian admitted that non-payment was running at “40-50% in several large towns and cities”. In London it was much higher. A correspondent commented: “I knew Thatcher was done for when I read that according to official figures a third of the people of Tunbridge Wells aren’t paying!” Jeffrey Archer, at the time not in disgrace, ruminated in public: “If we could go back I don’t suppose many of us would have brought in the Community Charge. It was a bad mistake.” [Militant 997, 15 June 1990.]

In the teeth of the campaign of mass non-payment, Thatcher was forced from office and her heirs in the Major government ripped up the poll tax. But that was not before brutal methods were used to try and impose the tax. This went from the use of sheriff officers in Scotland and bailiffs in England and Wales – massively resisted, led by Militant supporters– and the jailing of the leaders, as we have already reported. Although officially declared dead, the poll tax had not yet been buried completely. Indeed, eight months after the end of the poll tax, the pursuit of non-payers for arrears was continuing. One hundred and seventeen people had been jailed by November 1991 by 40 councils. Shamefully, 26 of these were Labour-controlled, including Burnley, which had actually imprisoned 23. At least ten pensioners received sentences totalling 366 days and ten women had been jailed. Amongst those jailed was Janet Gibson – partner of one of the leaders of the 2009 Lindsey strike – from Hull who refused to pay her poll tax and went to jail for two weeks. The knot of history – broken by the collapse of Stalinism – is being retied in current battles. Other Militants who were jailed included Eric Segal, Ruby and Jim Haddow and Anne Ursell in Kent, Mike O’Connell in London and many other heroic figures, with supporters of Militant and non-Militant workers resisting the tax by going to prison in defence of their class. £5 billion was owed to local councils from accumulated poll tax arrears.

The ending of the poll tax, officially, had actually led to more people refusing to pay. Without this struggle, the poll tax would still probably be in existence. It was the mass uprising, led by conscious socialists and Marxists, which led to its defeat and that of Thatcher. We must learn all the lessons for today in order to prepare for the tumultuous battles to come.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

Be the first to comment