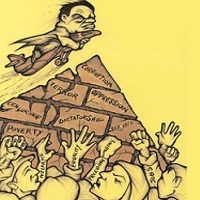

Authoritarian regimes in Middle East fear for their rotten rule

Following hot on the heels of revolutionary events in Tunisia, the Egyptian masses took to the streets during 18 tumultuous days. Now, all the authoritarian regimes in the Middle East and beyond fear for their rotten rule. This is, however, only the beginning of the revolution in Egypt. PETER TAAFFE assesses the current critical situation and possible developments.

IN RESPONSE TO the 1936 French mass strikes and sit-downs in the factories, from ‘distant Norway’, Leon Trotsky wrote: “Never has the radio been so precious as during these days”. How much more so – with the array of modern global communications – can we agree with those sentiments in relation to today’s Egyptian revolution! Millions and billions have had a grandstand view of the splendid unfolding of this drama. All other ‘distractions’ have been put in the shade: football matches between Egypt’s top teams were cancelled, perhaps the ultimate indicator of the effect of revolution!

We have written previously (see The Socialist, 10 February) that, even in a spontaneous revolutionary movement, the guarantee for a successful outcome in overthrowing the ‘ancien régime’ can often be found in the element of leadership present in the insurrection, and which has been prepared by the revolutionary forces in the previous period. This was clearly missing in what commentators dubbed the ‘leaderless revolution’. Yet such was the immensity – the human flood – and determination of the masses who occupied not just Cairo but all the cities of Egypt – six million on the day of Hosni Mubarak’s speech on TV, according to the Independent’s correspondent, Robert Fisk – that Mubarak’s act of defiance crumbled as he fled to his lair at Sharm el Sheikh.

A number of factors were responsible in finally prompting the generals to oust Mubarak. Undoubtedly, one was the occupation of Tahrir Square. It was bad enough for the regime that it was forced to tolerate the mass occupation of the square for a tumultuous 18 days – which represented an element of dual power where the street challenged the state machine. But when it began to grow in size and power after Mubarak’s infamous TV performance on Thursday 10 February, the generals took fright.

The biggest crowd ever gathered in the square. Ominously, some began to move towards the presidential palace, the TV stations, defence ministries and other centres of the regime’s power. This conjured up visions of a Serbian-type development, with mass occupations of the TV, etc, and all that flowed from this. Worse, with the prospect of a Tunisian-type storming and occupation of vital strategic interests of the regime, we now know that Robert Gates, US Defence Secretary, urgently contacted the Egyptian generals during the vital hours of Thursday night and Friday morning demanding Mubarak’s immediate removal. Even more threatening was the decisive emergence of the working class through important strikes – even factory occupations – which represents a new and decisive turn in the Egyptian revolution.

Element of surprise

THIS EARTHSHAKING 18-DAY convulsive revolutionary development – not the last word that will be spoken by the masses in Egypt by any means – took all layers of bourgeois public opinion and ‘opinion formers’ by surprise. The Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI) was not amongst those who were incapable of foreseeing these developments. In recent world relations documents, prepared for the tenth world congress of the CWI that met in December, we foreshadowed the removal of Mubarak (see: www.socialistworld.net).

This was not the case even with the most ‘informed’ commentators. Robert Fisk, whose reports for the Independent newspaper have best illustrated the revolutionary events, honestly confesses now, “I was wrong” to dismiss the likelihood of a revolt against the Egyptian regime. (15 February)

In a very informed piece in a recent issue of the London Review of Books, an observer speaks of the impression he drew from a visit to Cairo last year. There was, he writes, a widespread “myth of Egyptian passivity”. He reported an Egyptian journalist saying: “We are all just waiting for someone to do the job for us”. Another popular Egyptian sociologist also remarked that “Egyptians are not a revolutionary nation”, and he concurs that “few would have disagreed” with these sentiments.

On the surface, the molecular change in the mood of the masses was not obvious, particularly to superficial commentators without roots in the population, particularly the downtrodden workers and poor farmers. Actually, all the ingredients for revolution had been prepared beforehand, with a split in the ruling class, the middle class in opposition, and the workers and poor showing their colossal discontent with the worsening of their conditions, rising prices and the aggravation of mass unemployment. This was shown in the previous strike waves amongst the workers (see the CWI website) which convulsed Egypt and shook the ruling class at the time.

Moreover, there is a history of open opposition and rebellion to Egyptian regimes. The 25th January, when the revolution really took off, is itself the day on which an infamous massacre of demonstrators by British troops was carried out in Cairo – ironically, of police, who are universally hated in this revolution. There were also the revolutions against the royalty in 1952, and bread riots against both Anwar El Sadat – who preceded Mubarak – and Mubarak himself. The spark to ignite this current revolution undoubtedly came from Tunis. This was symbolised in the triumphal placard after Mubarak had exited: “A tale of two cities: Tunis and Cairo”.

A soft coup

THE JOY OF the Egyptian workers was unconcealed. One commented on the day that Mubarak fled: “We built the pyramids. Today is the fourth pyramid”. (Financial Times) At the same time, the consciousness that the revolution had not fully triumphed – full democratic rights remain to be implemented, and are in doubt so long as military rule is not dismantled – was evident in the views of many of the revolutionary fighters. One commented correctly that “we cannot stop with half a revolution”. In fact, a kind of ‘soft coup’ in the aftermath of Mubarak’s departure has effectively been carried out by the generals. The main elements of the Mubarak regime – landlordism and capitalism – have not yet disappeared.

The army reflects the social composition of Egypt itself. Conscripts make up about 40% of the army. They have been radicalised by the revolution, but so have significant layers of the officer corps, particularly the junior officers. During the 18 days, they remained sympathetic but mostly passive towards the revolution and the revolutionaries.

The generals, therefore, will attempt to restore strict military discipline. They are conscious, as Fisk commented, that the soldiers refused, when Mubarak gave orders for the tanks in Tahrir Square to open fire on 30 January, as fighter jets strafed Cairo in an attempt to cower the demonstrators. Tank commanders were seen turning off their headphones in defiance, many of them having contact with their families who demanded of them that they do not fire on the people. The increasingly democratic sentiment, itself reflecting the radicalisation of the middle layers of society, represents a mortal threat to the tops of the army.

Both the army elite and those they guard – big business and landlordism – believe that the masses’ job ‘is done’. They must now go back to sleep! Yet in the Observer newspaper, one defiant participant declared: “The revolution isn’t over yet”. Others commented: “We don’t want the military… They are not democratic”. An indication of the depth of the change that has been wrought was that even the former pillars of Mubarak, such as the government newspaper Al-Ahram, declared (of course, after Mubarak had safely fled Cairo): “The people ousted the regime… Egyptians had been celebrating until morning, with victory in the first popular revolution in their history”.

There are some illusions amongst the masses in the army as a kind of guarantor of the revolution. This is reinforced by those like Mohamed ElBaradei, who declared after Mubarak’s defiant speech that the army should take control in order to prevent an “explosion” in the country. This sums up the fear of the liberal capitalists of anything which threatens the economic and social foundations of capitalist Egypt. The capitalists understand that, ultimately, the army – despite its record of military rule over 60 years – is the guardian of ‘private property’, the wealth of the ruling class. Moreover, WikiLeaks has shown from diplomatic messages that Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, still the army commander-in-chief, wielded “significant influence [in Mubarak’s cabinet where he] opposed both economic and political reform that he perceives is eroding central government power”. Shashank Joshi, an analyst from the Royal United Services Institute, also comments that Field Marshall Tantawi “embodies the reactionary forces still embedded at the heart of the regime that may have shed its figurehead but not its essence”. (BBC website)

The threat of counter-revolution

FACED WITH THE choice of the status quo and a real revolution, particularly the socialist revolution, the ruling classes, including the army, will always choose the first option and accommodate themselves to reaction as the ‘lesser evil’. An Irish revolutionary, Henry Joy McCracken, once said: “The rich always betray the poor”. This is particularly true for the rotten landlords and capitalists which predominate in the neo-colonial countries.

In the first period, the representatives of the old regime are compelled to accommodate themselves to the new power. For instance, in the Russian revolution in 1917 – not only in August, when he attempted a crushing counter-revolutionary coup, but even soon after the February revolution, the reactionary General Kornilov schemed against the coalition of alleged workers’ representatives, the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries, and the capitalist parties. Kornilov offered the provisional government troops to put down the workers in Petrograd and crush their newly acquired rights, particularly the workers’ and soldiers’ councils (soviets).

This is a warning of what can happen if the revolution and the gains of the working class are rolled back. So also is the example of Chile in the 1970s. General Pinochet – the head of the army under the radical socialist government of Salvador Allende – used his position to prepare the coup which drowned the Chilean workers’ movement in blood. Revolution, unless carried through to a conclusion with the establishment of socialism, inevitably ‘provokes’ counter-revolutionary attempts on behalf of the remnants of the old regime.

So it was in the magnificent Spanish revolution with the attempt to seize power in 1932 by the reactionary José Sanjurjo. This was defeated because the revolution was not yet a spent force. But when they considered it opportune, reaction once again attempted to strike back. After the failure of the Asturian commune of 1934, which resulted in the ‘two black years’ (bieno negro), this prepared the way for another and even mightier revolutionary wave when the Popular Front was hoisted to power on the backs of the Spanish masses.

A golden opportunity to carry through a revolution was once more given – then, again, in May 1937 – but was squandered because of the false policies of the leaders of the workers’ organisations who formed a coalition – a strike-breaking conspiracy – with the liberal capitalists which rescued Spanish capitalism and prevented the socialist revolution.

A similar problem emerged in the Portuguese revolution which overthrew Marcello Caetano in 1974. To begin with, right-wing generals disguised their views. Then, in March 1975, General Spinola (the first formal leader of the revolutionary government) launched a military coup which was ignominiously defeated and actually ignited a revolutionary wave, resulting in 75% of the economy taken into state hands.

Military manoeuvres

A SIMILAR SCENARIO could open up in Egypt over time. It is not just the trappings of the Mubarak clique which should be removed but also the socio-economic power upon which it rested. The army tops are bound by a thousand ties to landlordism and capitalism. The head of the army, Tantawi, is one of the biggest owners of industry – in fact a series of industries – in Egypt. The Egyptian army is very similar to the Pakistani military elite in this regard: both own significant sections of industry and merge with the capitalist elite.

How can this officer caste be expected to demonstrate unswerving sympathy and support for the revolution? After the first stage, which has contained a big element of a political revolution – the removal of Mubarak without yet touching the economic and social foundations of his regime – they are seeking to manoeuvre to adapt to the revolutionary winds when they are in full force. But, once the working class decisively enters the political arena – as it has done magnificently in recent days through a series of strikes and occupations which go beyond the issues of wages and conditions by demanding, for example, the removal of corrupt management – the attitude of the officer caste undergoes a profound change. Combative strikes and demonstrations have broken out amongst workers in private and state manufacturing industries, as well as by ambulance drivers, transport workers, journalists and even the police, begging for ‘forgiveness’ over their past crimes.

Contrary to the impression given, not all sections of the army were ‘neutral’ or sympathetic to the revolution. Horrifying tales have emerged about army torture chambers in the Sinai and elsewhere in which brutal beatings and executions have taken place against opponents of Mubarak even during the revolution. Moreover, demonstrators have been arbitrarily picked up from the streets and subjected to similar treatment.

At the same time, there were significant sections of the officers who sympathised and joined the revolution. This, together with the example of the junior officers marching in the mass demonstrations, indicates that, at least at the lower level, the army has been infected by the virus of revolution.

At the same time, there will be growing opposition to the rich army elite at the base, including amongst the junior officers. Why should the army tops be the ones who alone decide on how the army as a whole should act in the course of the revolution? Not just the working class but the ranks of the army, too, need the means to express their views and suggest relevant action for society as a whole. It is true that, at this stage, the Egyptian army is not at the level of, for instance, the Portuguese army at the time of the 1974 revolution.

That army had been enormously radicalised by Portuguese imperialism’s war against the liberation movements in Mozambique and Angola. As a result, formerly right-wing officers were radicalised, came into opposition to the Caetano regime, with some seeking links with the organisations of the working class. As a result, they were open to the ideas of socialism, which deepened in the process of the Portuguese revolution itself. Similar situations have occurred in the neo-colonial world on occasions, for instance, in the Philippines.

But the officer caste in Egypt is bound hand and foot to the interests of the possessing classes. Moreover, under different US presidents, it has become an integral part of US imperialism’s ‘security’ framework for the Middle East. Mubarak was propped up essentially by the colossal tribute paid by US imperialism to Egypt, which amounted to $1.5 billion annually. A big portion of this, if not the majority, was doled out to the military, particularly to the summits.

However, in the aftermath of the immortal 18 days and their lasting repercussions, opposition and questioning of the army leadership have been fermenting amongst the lower ranks. This will grow and come into collision with the army tops. It is therefore necessary for the revolutionary forces to raise the question of fraternisation with the rank and file, to raise the slogan of linking the movements of the workers and the poor farmers together with the base of the army – through the organisation of committees of soldiers with democratic rights to propose changes in the army and in society.

Yawning class chasm

ALONGSIDE THIS, AND more crucially, is the overriding need now to build on recent important working-class struggles by beginning to construct workers’ committees in the factories and poor neighbourhoods, linked together on local, regional and national levels.

From the very base of society, amongst the most exploited and downtrodden workers and poor, a revolution naturally invokes sympathy and support. Even the ‘outcasts’ – normally almost unnoticed – have been drawn into the maelstrom of events. This is as true of the Egyptian revolution as those that have gone before. The homeless children of Cairo, as Fisk described, have been caught up in the revolutionary events. In heartbreaking accounts of these unfortunate victims of the system, numbering a colossal 50,000 in Cairo, Fisk describes how these children were caught up on the sides of both counter-revolution and revolution in the battles that unfolded. The demonstrators in the square in particular took many of them under their wing, gave them food and provided sleeping arrangements. This gives a glimpse of the solidarity towards the victims of landlordism and capitalism which the revolution has evoked.

Above all, the revolution provided an opportunity for the working class to advance its own demands of an industrial, economic but also political character. After all, it was the economic factors and the discontent which resulted from this which were the main driving forces of the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions. The deterioration in real wages, combined with astronomical price rises, particularly staples like food, drove the revolution on, affecting the middle class but, particularly, pushing those workers, the urban and rural poor, ‘over the edge’. According to official statistics, in a population of 80-85 million, 40% live in poverty, 44% of the labour force is illiterate or semi-literate, and a crushing 54% work in the ‘informal sector’.

A widespread and yawning chasm between the rich and poor has widened enormously under the impact of the world economic crisis. This was illustrated by workers who spoke to the Independent on Sunday about their wages and living conditions. Some payslips of weekly wages amounted to 400 Egyptian pounds a month (£42). A hospital anaesthetist commented that his gross pay was 700 Egyptian pounds a month (just £70). From this princely sum, this worker had to find £11 in taxes and £15 for electricity.

Seeking to mollify the workers who were rising in support of the revolution, Mubarak graciously granted to six million state employees a 15% increase in their salary – just before he departed the scene. This was merely a 15% increase in the basic salary, which amounted to no more than 20% of the total wages. Demands for a living wage, a shorter working week and all the other demands of the working class, including health and safety, should be reflected in a fighting programme for the struggles of the working class in the next period.

The call for an independent organisation of trade unions is vital. The state-backed trade unions are a sham. They imitate those that existed in the Stalinist states. Mubarak implemented a host of measures emanating from Stalinism, to which he and the Egyptian state were linked at one stage (he is a fluent Russian speaker). The lackeys and corrupt place-seekers in these organisations must be replaced with genuine, fighting trade union and workers’ representatives.

Independent workers’ organisation

AT THE SAME time, the incipient trade union movements in Egypt should turn their backs on the western-based tame trade union leaders who wish to ensnare them into accommodating Egyptian landlordism and capitalism. Such union leaders in the west invariably bend the knee to capital. The Egyptian masses did not rise up against Mubarak just for economic reasons. The logic of their struggle means that they must fight for the abolition of the system which has enslaved them, linking this to democracy. The acquisition of democratic rights is essential, including the vital ones of the right to strike and form unions.

But the working class needs its own organisations for struggle, both in the factories and in society in general. It is necessary that they have a powerful, independent voice in this tumultuous period, just as their Russian counterparts did in 1905 and 1917. The ruling classes will strive to create a ‘parliament’ in their own image, with their own representatives dominating. The masses must have ‘their parliament’ – workers’ and farmers’ councils – while fighting for a democratic constituent assembly.

There is a crying necessity, therefore, for a genuine trade union confederation of Egyptian workers. At the same time, this must be linked to the creation of an independent, flexible and democratic political expression for the organised working class. The equivalent of the mass committees, which were created in the Russian revolution and have featured in other similar movements in history, is vital for the working class of Egypt today. When, in the first Russian revolution of 1905, such committees were improvised, they were merely strike committees. None of the workers’ political representatives imagined that they would be broadened out into mass organs of struggle and, eventually, after the October 1917 revolution, into organs of power for the victorious working class. The demand for mass workers’ committees is not applicable in all situations as some on the left imagine. But it is legitimate to raise this demand in revolutionary periods, which is obviously the case in Egypt.

It is appropriate to form mass councils of action when there is a fundamental change in the situation, when revolution begins to unfold and the masses pour onto the scene. Kept in the dark night of 60 years of military rule, the Egyptian masses will be testing out all means to express their views and action to change their lives. This is not the situation yet in every part of the Middle East. But this demand does apply to Egypt at this stage and in the next period. The whole situation suggests the creation of such committees, which should also involve neighbourhood committees, small-business people, etc.

A revolutionary constituent assembly

ALREADY THE STRIKES have taken on not only economic and industrial characteristics but are, at bottom, political as well. This is shown in the strikes and occupations in some factories. Undoubtedly, these developments are of an incipient character. Nevertheless, they are symptomatic of how the Egyptian workers view the situation. A revolution is, above all, a great teacher of the masses, who learn more and with greater rapidity than in normal periods. A French revolutionary figure once said that, in the five years of the 18th-century revolutions, the French people had acquired more experience than in the previous six centuries! The 18 days in January and February were a period of educating and steeling the Egyptian workers in the processes of revolution and counter-revolution.

In order to sustain this, however, the working class needs to draw all the necessary conclusions. It is absolutely necessary to begin the process of creating mass committees today. At the same time, democratic demands and slogans arising from this assume a crucial character. The working class must fight to express its own independent position in society, jealously fighting for and guarding its independent existence, especially from ‘well-meaning’ but fatally flawed liberal capitalists.

It must also champion, in fact, be the best advocates of, a democratic programme and democratic rights. This is the only way that the working class can put itself at the head of the downtrodden sections of society – the farmers, urban poor and sections of the middle class – who see the gaining of democratic rights as the most urgent task in the situation which obtains in Egypt today. Democratic slogans, such as a free press – including the nationalisation of printing press facilities accessible to all trends of opinion, particularly the working class – and the right of free assembly are necessary.

But the most important demand of a general character is for a democratic parliament, a constituent assembly. The regime has announced that elections will take place in six months. In recent days, it implied this could be as early as in the next two months. It is quite clear that the possessing classes, even when they are prepared to concede some democratic rights, are not in favour of real, honest democracy accessible to all. No trust in the generals or the ‘higher-ups’ to construct a genuinely democratic Egypt! In the last few days, the generals have appeared in their true colours by calling for the end of strikes, which ‘cause chaos’. This is their price for dangling the prospect of limited ‘democratic reform’.

In answer to this, workers should demand that, alongside the independent workers’ and poor farmers’ councils, the overall democratic programme should be crowned by the call for a constituent assembly, which can only be revolutionary in character given what will take place in the context of the unfolding revolution. Moreover, such a body can only be convened if it represents the majority, the toilers in the towns and countryside. Committees to ensure that the elections are properly organised, that votes are not bought as in the past, will be absolutely essential.

We differ completely from all pro-capitalist formations that have also raised the question of a ‘constituent assembly’ in a general way. The working class has no interest in a regime in which the president has the ultimate say. This was the regime of Mubarak, Sadat and, before him, even Gamal Abdel Nasser. The working classes were elbowed aside as were the poor masses. We are against a second chamber which is invariably used as a check against the more radical demands of the working class and poor. One chamber in democratic elections to a revolutionary constituent assembly should be the watchword of the Egyptian masses.

Such a demand, taken up in a mass campaign by the revolutionary forces would, have an enormous effect in the charged situation in Egypt. It will be furthered by the creation of a new mass workers’ party which would give a voice to the forgotten and voiceless masses. The working class should fight for class independence, particularly from false friends who emanate from the ‘liberal’ wing of Egyptian capitalism.

International repercussions

THE EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION was not just an event for the country itself, but was a Middle Eastern and world phenomenon. The Egyptian masses have shaken to the foundations the imperialist powers who believed they held all the reins in their hands. One placard held up in the post-Mubarak celebrations summed up the regional effects of the revolution: ‘Two down, 20 to go’. First, Tunisia and now the Egyptian revolution. Of course, they will not be automatically replicated in every detail or at the same rhythm throughout the region.

There is not one stable regime in the region, as the CWI commented last October. The most reactionary regimes in the Gulf states, the semi-feudal potentates, are trembling before the magnificent movement of the Egyptian workers. Already in Jordan, the echoes of these movements have been reflected in mass demonstrations, as they have in Algeria and in Morocco, with 18% graduate unemployment and where mass movements cannot be ruled out. In Yemen, the president has promised to vacate office. However, his attempt to hold on to power for two more years is untenable. He could be toppled by a mass movement in the next period.

The balance of forces has decisively changed in the region. One of the most frightened regimes is undoubtedly what appeared to be the ‘strongest’, Israel. Hitherto, the Israeli ruling class was backed up by the Mubarak regime through the shameful embargo imposed on the starving, miserable Palestinian masses of Gaza. At the same time, the Suez canal is being used as a vital economic and strategic military factor for bolstering Israel. Most nauseating is the posture of those like Tony Blair and Hillary Clinton, US Secretary of State, towards their ‘personal friend’ Mubarak and his successors. Blair, as is widely known, used the facilities in Mubarak’s holiday homes.

The Israeli working class, which recently has come into collision with its own government, will also have been affected by the Egyptian revolution. A democratic socialist Egypt would initiate close collaboration between the working class in both countries, leading to a real and lasting peace through a socialist confederation of the Middle East.

A medium- and long-term consequence of the events in Egypt could be the opening up of the scenario of another war. But the most important ‘war’ to be fought in the region is the class war. Clearly, a new page in history has been opened up in the region and the world, particularly for the working class. All the forces striving for a socialist world – the Socialist Party and Committee for a Workers’ International – salute the Egyptian working class and fervently hope and expect that that this opens up a new favourable chapter in the movement of the working class throughout the world.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | ||||||

Be the first to comment