An immense struggle between the workers’ movement and big-business leaders

Introduction by Manny Thain

The working-class forces were led by the pioneers of Irish trade unionism and socialism, Jim Larkin and James Connolly. Alongside of them stood thousands of activists and their families whose heroism laid down the foundations of the workers’ movement in Ireland.

They faced an all-out offensive from the bosses, behind William Martin Murphy, owner of the Dublin United Tramways Company, at the centre of the struggle, boss of Independent Newspapers and many other companies and business interests. Murphy and co were determined to smash the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), founded by Larkin in 1909.

By August 1913, Murphy had brought together nearly 400 employers. They demanded that all workers sign an undertaking not to join the ITGWU or any trade union. Those who refused were sacked. This was at a time of severe economic crisis.

Larkin called out the workers at the Dublin Tramways Company on 26 August. In the subsequent months, Larkin and countless others would face arrest, imprisonment and brutal police repression.

By 22 September, 25,000 workers were locked out by a succession of companies. The conditions of working-class people deteriorated, highlighted by the plight of starving children.

By November, James Connolly was at the head of the trade unionists’ Irish Citizen Army. Dublin port was closed down by strike action. Jim Larkin embarked on a tour to build support from the British workers’ movement. Despite huge rank-and-file solidarity, however, leaders of the TUC organised to block official action. Against all the odds, the struggle in Dublin continued up to the end of February 1914.

To commemorate the 1913 centenary the Socialist Party in Ireland has published a new assessment of this heroic struggle. Let Us Rise not only examines the events of 1913, it also argues that the struggle is extremely relevant to the situation in Ireland today. Facing a brutal assault on living and working conditions, in the form of savage government-driven austerity, workers in Ireland have no alternative but to fight back.

In the examples of Jim Larkin, James Connolly, the thousands of rank-and-file activists, and determined, mass united working-class action, the Dublin lockout can shine a bright light on the way forward for the workers’ movement today. But it can only do so if the lessons of that struggle are fully absorbed, and if the trade union movement gets off its knees.

’Let Us Rise’ is an important contribution to drawing those lessons. And we print below an extract from the concluding chapter, written by JOE HIGGINS, Socialist Party TD (member of the Irish parliament), responding to attempts by union leaders today to rewrite the history of the Dublin lockout for their own purposes.

There is a huge amount to celebrate about the 1913 Dublin Lockout. The ability of the men and women to conduct a mass struggle against a cartel of big-business interests with unlimited resources for more than six months and the fighting methods used helped establish a tradition of industrial militancy that was essential to win better living standards and rights in the decades that followed.

The events of 1913 were a revolt against the brutal conditions of capitalism. Unfortunately, we still have the same system today, now wracked by potentially the worst crisis in its history, where rights and conditions are being savaged with no end in sight. A majority of people in Ireland are opposed to the draconian austerity imposed since 2008 by two different governments. The establishment parties decided that the European financial system and its big bankers and bondholders should be bailed out from the financial crash resulting from decades of liberalisation, privatisation and unbridled speculation and profiteering.

In celebrating 1913, the Socialist Party wants to give an accurate representation of the events, as many others, including some trade union leaders today, have reasons for distorting what happened. It is important to put the record straight, and to take up comments made by Jack O’Connor, general president of the Services Industrial Professional and Technical Union (SIPTU), on 30 January this year, in a speech to mark the 66th anniversary of the death of Jim Larkin, one of the main leaders of the Lockout.

During the Lockout, the sacrifices made and the fighting spirit and dignity displayed by the workers throw into sharp relief the mouse-like timidity of the main trade union leaders of the present day. Yet even they have to celebrate Larkin and 1913. On the one hand, they try to reflect the glory of this historic struggle as their own reputations continue to slump among working-class people because of their failure to fight or provide any alternative to austerity. On the other hand, they also must subvert the real meaning of 1913 and what Larkin stood for in order to try to camouflage their dismal role today.

On 9 February this year, 50,000 to 60,000 people marched in different locations around the country on a day of action called by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU). In ‘normal’ times this would be a significant turnout. However, given that opposition to austerity is growing, the turnout was only half what the ICTU was aiming for and indicates that it has lost its authority among broad sections of workers.

For the rally at the end of the Dublin march, the ICTU had a huge screen erected on Merrion Square. Powerful images of Larkin addressing workers were displayed. The cynical hypocrisy of this was evident as David Begg, general secretary of the ICTU, in a brief speech, advanced no plans for real action to fight austerity. Insult was added to injury when this was followed only by singers and comedy acts. Perhaps because they would know me as a long time Socialist Party public representative, I was approached by group after group of workers registering their utter disgust at the ICTU.

Jim Larkin

Jim Larkin Subverting Larkin’s legacy

Jack O’Connor was formerly an official with the Federated Workers Union of Ireland (FWUI). It and the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) were the two unions that Jim Larkin founded. In 1990 they united to form SIPTU, by far the biggest union in the state. While O’Connor complimented Larkin, even speaking positively about his Marxist analysis, the speech was an attempt to abuse Larkin’s legacy to justify the inaction or, more accurately, monstrous betrayal of the general trade union leadership today.

Standing alongside Larkin’s grave in Glasnevin, Jack O’Connor said: “They [left-wing critics of the trade union leaders] assume that Jim Larkin, were he alive today, would lead the charge. They conveniently forget that Larkin did not start the great Dublin Lockout, and that, in fact, he counselled members against voting for strike action on 25 August 1913. Larkin also called for binding arbitration during the course of the dispute to end the employers’ offensive. Of course, once war was declared, Jim Larkin fought to win with every morsel of his being… But the reality was that, no less than any leader, and he was a brilliant leader, he would not choose to lead vulnerable men and women and their families into a head-on collision with overwhelmingly superior forces…

“We were not prepared to lead tens of thousands of workers into an enormous confrontation in which they would be depicted as a minority of one-sixth of the workforce jeopardising the interests of the other five-sixths”.

The reality is that, since mid-August 1913, Larkin had been trying to spread the boycotting of newspapers owned by William Martin Murphy, who was at the forefront of the assault on workers’ conditions and their organisations. Since July, Larkin and the ITGWU had been engaged in efforts to recruit workers at the Dublin United Tramways Company (DUTC), which Murphy also owned, in preparation for action. Larkin was aware that Murphy was preparing, too, but caution regarding the DUTC was mainly because he wanted to try to ensure the support of the workers at the DUTC power station in Ringsend before taking action.

On 25 August, Larkin did caution tramway workers who were straining for a fight but, at the end of the meetings that very night, he called the tramway workers out on strike, effective the following morning.

The significance of his support for the ‘conciliation board’ and arbitration, as a basis for negotiation, is also overstated by Jack O’Connor. The proposals were that the ITGWU would give an undertaking not to use sympathetic strike action against employers who were willing to refer disputes to a conciliation board made up of employers and the unions. It was also proposed that Murphy would have to withdraw the employers’ form which demanded people leave the ITGWU and disassociate themselves from it, and that all workers locked out would be reinstated.

Conditions were very difficult for the workers and their families. A truce on those or similar terms would have undermined the momentum of the bosses and made their aim of smashing the ITGWU difficult to achieve. There is no question that Jim Larkin or James Connolly, the other giant who helped form the modern trade union movement in this country, had any illusions in conciliation boards or binding arbitration, but judged them tactically beneficial in the particular circumstances at the time. It was indicative of this reality that the bosses made it clear they would not accept any such initiatives.

Jim Larkin would not propose strike action at the drop of a hat, but he did believe that workers withdrawing their labour, and using their powerful position in industry and commerce to undermine a boss’s profits and the system, was the only real way to win concessions from capitalists.

Implying that Larkin would acquiesce in the face of brutal austerity and accept the draconian destruction of workers’ living standards and jobs – as the present day trade union leadership does – flies in the face of everything we know about his role in 1913. We should reject with contempt this effort to weave the legacy of Larkin and 1913 into a tapestry of justification for the betrayals of the present day.

The power of the working class

I believe Jim Larkin would also dispute the assessment that the forces pitched against the working class were, or are, “overwhelmingly superior”. Larkin believed that, if organised, the working class is the most powerful force in society. But, even if it is in a specific instance weaker, once war was declared Larkin would fight “to win with every morsel of his being”, as Jack O’Connor himself admits.

I reject O’Connor’s estimation that the trade union movement of today is incapable of waging a serious struggle that could win out over the forces of austerity. The ICTU website claims that over 830,000 workers are in ICTU-affiliated unions, more than 600,000 of them in the South. Those members plus their families mean that the trade union movement has enormous potential power, the like of which Jim Larkin could only have dreamt of.

To suit his argument, Jack O’Connor narrows the focus to public-sector workers and the original Croke Park deal of June 2010, which introduced harsh public-sector cutbacks. He then says how difficult it would have been for public-sector workers, one-sixth of the workforce, to take action that inevitably would have affected everyone, implying such action would have been deeply unpopular. Yet, austerity isn’t just a public-sector issue. All workers are affected by cuts. Wages are being attacked in the private sector and more cuts to public-sector wages will re-enforce a race to the bottom for all.

Instead of retreating in the face of the establishment’s attempt to divide public and private-sector workers, the unions could and still should organise united action of all workers, building towards a general strike to force an end to austerity. Jack O’Connor also feels that he and other union leaders, as well as Labour Party politicians, are playing a progressive role by accepting austerity deals and programmes that supposedly soften the blows being struck and that workers should be grateful for this. In reality, these union leaders are assisting the government and bosses to achieve all that they want.

In the class struggle, weakness invites aggression. The concessions given in the original Croke Park deal didn’t halt the slide but just whetted the appetite of the super-rich for more. This failed approach led directly to the additional devastating cuts contained in the Croke Park 2 and Haddington Road deals.

The overwhelming rejection of Croke Park 2 in April demonstrated the deep discontent with austerity and the approach of the main unions. The subsequent acceptance by some unions of the Haddington Road deal was only achieved by demoralising workers into not voting a second time, as they had no confidence that these ‘leaders’ would do anything.

If the trade unions had fought austerity and forced a change of policy, people’s economic position now would be significantly better and the working class would be a more cohesive force capable of fighting back.

A political issue

Jack O’Connor’s attempt to recruit Jim Larkin in the service of the ICTU leadership and the Labour Party is cynical revisionism. Larkin’s fighting approach was rooted in instinctive intolerance of injustice but, crucially, was also informed by his political outlook.

He understood that the working class produces the wealth in society; that under capitalism there is an irreconcilable struggle over the ownership of wealth and capital; and that the only way a secure future can be developed for the majority is on the basis of social ownership of the economy in a democratic socialist society. For Larkin, there was always a purpose in working-class struggle because the capitalist class always has something to give but, most importantly, because organised mass struggle is the way to break with capitalist exploitation altogether, which was the prime goal.

For the dominant trade union leaders today struggle is something from the past or to be threatened in holiday speeches, but not acted upon. In fact, for them, struggle must be resisted as it undermines the chance for successful negotiation and compromise. They ignore the brutal reality of capitalism and refuse to recognise that it has no solution to this crisis, that the crisis is organic to the system itself.

Jack O’Connor talks of legal protection, collective bargaining and voting for the Labour Party in greater numbers, as if these constitute a decisive way forward. He says: “Undoubtedly, Larkin would have scolded the Labour Party… but he would not have succumbed to the simplistic folly of blaming Labour for the problem, which perfectly plays to the agenda of those on the right of the political spectrum…

“Jim Larkin would have faced up to the challenge of the inconvenient truth that 60% of those who went out to vote in the last election voted for those who guaranteed the better off that they would not have to pay a wealth tax or a higher rate of tax on their incomes. He would have framed the challenge in terms of the need to convince sufficient numbers of those who voted for these parties to shift their allegiance to some combination on the left that represented their true interests”.

It is incredible to assert that Larkin would not hold the Labour Party to strict account for its implementation of austerity to bail out big bankers and bondholders. Jack O’Connor attacks working-class people who did not vote Labour in the 2011 general election, implying that a Labour government would have stood up to the markets and the troika.

The reality is that Labour inspired no confidence that it would represent a fundamental break from the political and economic establishment, or be anything different to the Blair/Brown governments in Britain. Yet the electoral annihilation of Fianna Fáil and the Green Party represented a massive rejection of austerity and should have been the signal for the labour movement to launch a major offensive and to outline a radical alternative.

Jack O’Connor

Jack O’Connor What happened after 1913?

Jack O’Connor’s view of history is as distorted as his view of the present. He says: “The battles fought out on the streets of Dublin between August 1913 and January 1914… were the nearest thing we ever had in this country to a contest between the values of labour in Ireland and the outlook that would shape the country for the next century.

“Ultimately, the battle was won by William Martin Murphy and his allies despite the heroic resistance of the working people of this city and we have been living with the consequences of the victory of that wealthy elite ever since… It has led us to an economic crisis which threatens our very existence as a sovereign state for the third time in 60 years”.

The Lockout can only really be described as a defeat in the immediate sense of the specific battle and its immediate aftermath. In a broader sense, the Lockout had an important positive effect on the activists who came after it. Within three years, the workers’ movement began to recover.

Inspired by events like the Russian revolution, a mass movement exploded after 1917. It included a successful general strike against conscription in 1918, a soviet in Limerick in 1919, a virtual soviet in Belfast in the same year, another general strike in 1920, major electoral successes for Labour, and a huge interest in left and socialist ideas.

A major factor driving the desire for national freedom from British imperialism had been the desire for fundamental change in the social and economic conditions of the masses. In the North, however, a struggle for independence could only have obtained mass support across both communities if the labour movement had adopted a sensitive approach, not only to the particular oppression of people from a Catholic background but, crucially, also to the fears of the Protestant working class that independence could lead to industrial decline and poverty, as well as ‘Rome rule’ and discrimination. It would have had to explain that the prospect of a socialist transformation would benefit the whole working class, from all backgrounds.

This process towards social revolution was undermined when the leaders of the labour and trade union movement agreed to the ‘Labour must wait’ dictat in advance of the general election of 1918, and allowed Sinn Féin to take the lead in political events. During the class revolt and profound radicalisation that swept the country from 1917 to 1922, the potential for social revolution against capitalism reached its highest point in Ireland. It was in fear of this and its effects on the working class in Britain that British imperialism chose to partition the country, using sectarianism and divide-and-rule tactics to try to derail the socialist threat.

The urgent need to change course

By arguing that the outcome of the Lockout set in train negative consequences that sealed the fate of the working class, Jack O’Connor is also absolving the leaders of the labour movement of their responsibility in squandering other important opportunities to decisively change this state.

These include the huge movement against the unfair income tax levied on ordinary workers. The movement exploded in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with 200,000 workers marching in Dublin on 20 March 1979, mobilised by the Dublin Council of Trade Unions. Then, on 22 January 1980, 350,000 workers marched in Dublin – over 700,000 throughout the country – the biggest demonstration of organised labour ever in this country. Yet the trade union leadership refused to turn it into a real challenge to the system.

During the 1982-87 Fine Gael/Labour coalition the trade union leadership again blocked struggle against savage cuts. When Charles Haughey’s Fianna Fáil came back into power in 1987, with the intent of imposing even worse austerity, the unions were forced to reflect the anger, including a one-off public-sector strike. There was also some action by teachers and nurses. By the end of year, however, the trade union leaders had signed up to ‘social partnership’ which ruled out the possibility of any serious industrial action.

The main trade union leaders and senior officials are completely disconnected from the harsh realities of life that ordinary workers are experiencing. Jack O’Connor’s basic salary is around €115,000 a year, roughly three times the average industrial wage, never mind the average wage. I also understand that Shay Cody, general secretary of IMPACT, the other particularly pro-government/partnership union, has a basic salary of around €160,000 a year. (Irish Independent, 23 September 2012)

What would James Connolly, Jim Larkin and the men and women of 1913 make of such wages and leaders? In 1913 Larkin regularly took no pay to save the union’s funds for the struggle. Just as the working class has the potential to be the greatest force in society, if organised, it also has the power to take the trade unions back, and this must be taken up immediately.

The anniversary of the great Lockout is provoking widespread discussion. The steely commitment of the force of nature that was Jim Larkin, the example of the courageous and organisational giant that was James Connolly, and the endless heroism of the working-class men and women who surrounded them, will inspire workers and young people to learn the rich lessons from their struggle and to become active in the movement. Now is the time to transform the unions into the instruments of real solidarity and class struggle for which they were established – and to build support for genuine socialist change in Ireland and internationally.

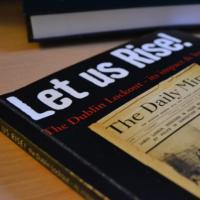

Let Us Rise!

The Dublin Lockout, its impact and legacy

Various authors

Published by Ashford Press, 2013

Available from Socialist Books, £5 (plus £1 p&p)

Chapters include:

The Gathering Storm: the lockout in its wider national and international context.

Class War in Dublin: the events as they unfolded.

No More the Slaves of Slaves: the key role played by women.

Solidarity Across the Sea: workers’ support internationally – and the betrayal of the British TUC.

More than a Taste of Power: the revolutionary struggles in Ireland 1917 to 1922.

Larkin and the Unions Today: a response by Joe Higgins to attempts by union leaders to rewrite the history of the Dublin lockout for their own purposes.

Be the first to comment