A new book offers important insights into the role played by Middle Eastern states in the rise of brutal reactionary forces such as Islamic State. What’s missing, however, is an assessment of the potential of the mass movements in the region.

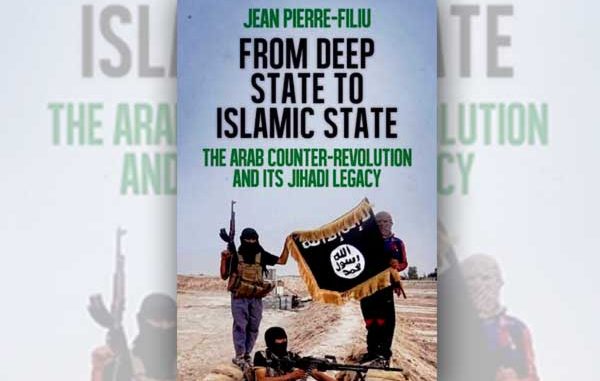

’From Deep State to Islamic State’

By Jean-Pierre Filiu

Published by Hurst (2015), £15-99

Jean-Pierre Filiu’s book comes in handy for all those who want to learn more about the background to the earth-shattering transformations and turmoil that the Middle East has been going through recently. It is rich in facts, details and anecdotes, erecting a dark but realistic picture of the machinations of the region’s ruling elites, their military intelligence systems, and their entrenched patronage networks which have worked to sideline and crush all forces that stand in their way. This book provides a good historical appraisal of the counter-revolutionary machines that have been running at full capacity in the last five years, following the first spark of the so-called Arab Spring, set off by the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, in December 2010.

Filiu starts by going back to the Turkish roots of the expression ‘deep state’. The Susurluk scandal in 1996, which exposed the underground connections between the Turkish far-right, criminal gangs and security forces, and their tight collaboration in the struggle against the pro-Kurdish PKK guerrillas, came as an electroshock to ordinary people. It represented a watershed in Turkey’s politics, in effect clearing the way for the rise of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), which portrayed itself as a clean political entity ready to have a showdown with this much feared deep state. This had some similarities with the Mani Pulite (Clean Hands) scandal in early 1990s Italy, which paved the road towards the ascension of Silvio Berlusconi. As Filiu puts it, however, the AKP’s upswing from 2001 onwards became only a “petty manoeuvre to replace one unruly repressive machine with a docile one more to his [Erdoğan’s] own liking”. Unruly, repressive, and utterly corrupt too, as indicated by the series of scandals which have marked the AKP’s rule in the last few years.

As his book was released before the summer, Filiu could not have known about Erdoğan’s military assault against the PKK and the Kurdish people in the south east of Turkey. Nor could he know about the savage bombing attack that killed over 100 workers, left and pro-Kurdish activists in Ankara on October 10. But if anything, it shows that the ‘peace process’, which Filiu describes as the only “formidable achievement” of Erdoğan’s rein, is in tatters, like the rest of the AKP policies.

The CWI, however, long ago warned of the possibility of a return to a situation of open armed conflict, as none of the fundamental problems underlying the national question in Turkey and in the region have been addressed. But Filiu proceeds with what comes out as an essentially empirical approach. In the foreword he admits: “My focus on the Arab revolution prevented me from assessing the full potential of the Arab counter-revolution”. Unfortunately, empiricism stays with him when he goes on to focus his newly acquired attention on the current Arab counter-revolution and its intrinsic sources, this time by forsaking the role played by the masses in shaping the political developments in the region.

Hijacked revolutions

Indeed, embroiled in the intrigues, plots and dirty games of the ‘deep states’, he sometimes gives the impression of being unwilling to get out of them. Filiu graphically illustrates the hijacking, in the post-second world war context, of the anti-colonial revolts and pro-independence struggles by the ‘modern Mamluks’, as he calls them. (Mamluks refer to a military caste, in contemporary terms repressive regimes based on large military apparatuses, systematic plundering of national resources, and regularly staged electoral plebiscites to legitimise their rule – as in Algeria, Egypt, Syria and Yemen.) But he pays hardly any attention to the struggles themselves, their strength and weaknesses, their political programmes, strategies and leaderships.

Hence Filiu fails to explain how these hijackings could have been avoided. He does not explain how the region’s once-powerful Communist parties, responding to the dictates of the Stalinist bureaucracy in the Soviet Union, helped to hold back the growth of the labour movement across the region, by subordinating its struggle to power-hungry military leaders and pro-capitalist nationalist forces, rather than guiding the millions of workers and peasants striving for change down the road of a genuine socialist transformation of society. The cold war period and the existence of the Soviet Union allowed some margin of manoeuvre to the regimes in the region, and led some of them towards confrontation with western imperialism and deep incursions into the prerogatives of the traditional landlords and capitalists. But the collapse of the USSR saw the process go into reverse, with the unleashing of mass privatisations and the warming of relations with the west.

On the ashes of a largely defeated left, and of the despair and disillusionment of some of the poorest sections of the Arab masses, the forces of right-wing political Islam grew. Indeed, they were often cultivated within the wombs of the Arab dictatorships as a counterweight against the left. Osama Bin Laden’s first attack, for example, was conducted as a covert anti-communist operation in Southern Yemen, with the full knowledge of the Saudi and North Yemeni intelligence. In its turn, the jihadi factor, as explored by Filiu in the chapter, ‘The “Global Terror” Next Door’, from the 1990s and especially after 9/11, became the new pretext for the Mamluks to boost their security apparatuses and tighten their relations with US imperialism. This was exemplified by ex-Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh: “Less than a year into office, the Obama administration decided to dramatically increase US support for Yemeni security: military aid boomed from $67 million in 2009 to $155 million in 2010”.

The success of curbing the terrorist threat through such all-out repressive methods can be measured by the devastated state of Yemeni society today. Al Qaeda flourishes as never before in the southern provinces, boosted further by the chaos and destruction provoked by the Saudi-led bombardment of the country over the last few months. Similarly in Egypt, as Filiu argues, “when it came to jihadi terrorism, [current president] Sisi’s record was already ten times worse than [deposed president] Morsi’s (28 deaths, mostly in Sinai, from July 2012 to June 2013; against 281 victims, 40% of them on the Egyptian mainland, in the following eight months)”.

Cynical, hypocritical elites

Filiu’s book has its merits. He thoroughly exposes the narrative of Arab elites who regularly use ‘anti-imperialist’ and ‘anti-Zionist’ rhetoric while having, in the last analysis, “established their ruthless regimes on the ruins of the anti-Israeli resistance”. For instance, the Black September massacre in Jordan in 1970 was a defining moment in consolidating Hafez al-Assad’s dictatorship in Syria. Large numbers of Palestinians and Jordanians who had risen in a mass revolutionary uprising against the corrupt regime of King Hussein were defeated in a bloodbath – as a result of the betrayal of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) leadership. Having no wish to see Hussein overthrown, because he feared revolutionary repercussions at home, Assad allowed the Syrian tank forces under the control of his rival, Salah Jadid, to be mauled in Jordan, thus paving the way for the discrediting of Jadid and his eventual demise.

Nine years later, Egypt under president Anwar Sadat, in a context of growing economic liberalisation by the regime, signed a US-sponsored peace deal with the Israeli ruling class, its armed forces being rewarded for their loyalty with an annual transfer of $1.3 billion in American military aid, which has continued up to this day. Sisi’s support for the Israeli army’s ‘Protective Edge’ offensive on the Gaza strip in the summer of 2014, and the Assad-orchestrated blockade and killing of Palestinian refugees in the open-air prison camp of Yarmouk in Damascus in recent years, are in line with Filiu’s observation: “No counter-revolution should be complete without the liquidation of the Palestinian cause”.

Filiu also refuses to fall into the trap, dear to most liberal commentators (and to some on the left), of attributing secular credentials to regimes and rulers who crack down on anything they decide to label ‘terrorists’. The dichotomy ‘secularism vs Islamism’, presented by some as the cultural combat of our times, is swept away by clear examples. Talking about 2011, Filiu recalls that “paradoxically, the Muslim Brotherhood became the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces’ closest ally during this volatile period. The Islamist organisation had proved ready to strike a deal with Suleiman, to the dismay of the Tahrir activists, days before Mubarak’s fall. They were now open to a tacit agreement with the top brass in order to hold general elections that they were confident of winning”.

Similarly, Filiu recalls that the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, the son of Hafez – still presented by some on the left as ‘secular’ – had played with the jihadi fire long before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. Assad gave backdoor support to Sunni insurgents after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, just as he let numerous jihadists sneak into northern Lebanon after his occupying troops were forced out of that country by a mass movement in 2005. Again in 2011, to sustain his own propaganda of a rebellion stirred up by ‘terrorists’, Assad organised the release and amnesty of notorious jihadi leaders.

The chapter, ‘The Algerian Matrix’, dealing with the ‘dirty war’ of the 1990s, reminds the reader that between the extreme brutality of the state repression and the maddening violence of jihadist groups, it is, as in Egypt today, a choice between plague and cholera. Filiu implicitly points at the price to pay if an independent alternative to both is not built. The failure of achieving this during the ‘Algerian Spring’ of 1988 left the road wide open for a major show of force between two crews of ferocious reactionaries. In passing, Filiu provides an interesting figure which tends to cut across the simplistic and ideological contrast made by many mainstream commentators between ‘legitimate refugees’ and ‘illegitimate migrants’: “110,000 Algerians left their country during the ‘black decade’ of the 1990s, compared to 840,000 during the 15 years following Bouteflika’s election in 1999. So the ongoing stagnation has proved more devastating for the long-term hopes of the Algerian youth than the horrors of the civil war”.

Mass pressure

The very broad portrait the author wishes to paint by giving insights into a vast number of regimes of the Middle East, the Gulf and North Africa, can come across as overly ambitious. The sum of information is quite exhaustive and sometimes even overwhelming. On the other hand, the book falls short of dealing with all the factors behind the deep states’ resilience in the face of the powerful mass revolutionary movements that have shaken their rule since 2011 – among which these regimes’ own might is only one aspect.

Another critical aspect should involve a serious analysis of the revolutionary and protest movements’ own political and organisational characteristics. While sometimes hinting at the vital part played by the working class as a driving engine for revolutionary change – “Apart from the fundamental Mamluk characterisation of Egypt against Tunisia, the main difference between the two countries is the vitality of the labour movement in Tunisia” – Filiu never draws any conclusions from these episodic remarks.

On the contrary, he embellishes the Tunisian experience to the point of falling back into the commonplace ‘success story’ narrative, the one in which the class character of the revolution is swept under the carpet and in which politicians from the old regime are crowned as would-be democrats. “Tunisia proved that there was an alternative”, writes Filiu, “but the Deep State had to be neutralised and the Mamluks were bound to lose some of their dearest privileges”. The author here falls back into his original sin of disregarding the threat of the counter-revolution: by neglecting, for instance, issues such as the new ‘economic reconciliation law’ that the Tunisian government is presently pushing through. This is the source of important street protests as it is aimed at whitewashing the crimes of corrupt businessmen linked to the old regime and restoring precisely their ‘dearest privileges’.

Filiu does not seem to grasp fully how capitalist economics work. The last notes of his book, referring to the fall of oil prices by 40% in 2014 as “just one ray of hope in this bleak landscape”, sound almost childish after the lengthy descriptions given in the 252 previous pages. He writes: “Cheaper oil could alleviate the devastating pressure on Arab society and polities, in the same way that absence of oil was crucial to the success of the Tunisian revolution”.

This is not a very sound argument. In some cases, the fall of oil prices has actually been used by the ruling classes to justify attacks on the working class. The Moroccan government, for example, has exploited lower oil prices in order to implement structural cuts in state subsidies on energy. The full effects of these cuts and the popular resistance to them have been limited for now by the conjuncture, but will eventually hit the poorest hard once oil prices go up again. For the elites of those regimes heavily dependent on oil revenues, the fall of this financial valve means they will intensify their offensive against workers and poor to make up for the difference and keep their pockets full.

The shale gas prospecting in the south of Algeria, in total disregard for the environment and for the health and safety of the local populations, provoked a mass wave of protests at the beginning of this year. It is yet another example of how the fall of oil prices is not automatically alleviating pressure on society. That can only happen if the masses are capable, through their struggles and their political organisation, of building an entirely new society, based not on the greed of a ruling few, but on the public ownership and democratic planning of resources according to the needs of all: a socialist society.

Overall, despite its flaws, this book remains a fascinating comparative study, carrying us through the intricate and fast-moving corridors of the Middle East’s state structures – even at the risk of losing some readers along the road.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Be the first to comment