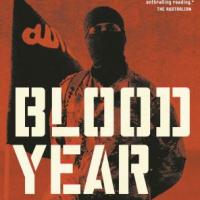

Published earlier this year before the Chilcot report was finally released, Blood Year by counter-insurgency strategist David Kilcullen is a damning indictment of the so-called war on terror unleased by US imperialism in 2001, with the full support of Tony Blair.

’Blood Year: Islamic State and the failures of the war on terror’

By David Kilcullen

Published by Hurst (2016), £9.99

Blood Year is a minutely detailed picture of chaos and violence, a record of the horrific consequences of the US-led war on terror unleashed from 2001. It tells the story of US state hubris – that, as the world’s only super-power (in the first decade of the 21st century, at least), it felt it could act with impunity to further its political and economic interests.

It is written by an insider. David Kilcullen was an Australian army officer with an expertise in guerrilla warfare and Islamist forces in Southeast Asia. He had helped draw up the Australian state’s counter-terrorism strategy, before being seconded to the US, working at the highest levels of the Pentagon and government. He was also on the ground in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, the Horn of Africa, Southeast Asia, wherever there was a warzone and US capitalist interests.

Kilcullen writes a critical account, highlighting strategic and tactical mistakes. He states bluntly that invading and occupying Iraq was a major error, and a complete fiasco. What Kilcullen really exposes, however, is the inability of world capitalist powers to deal with the monster they helped create – global networks of right-wing political Islamists and their franchises. Moreover, how capitalism has no answer to the poverty, instability and sectarian division inherent in the system and which lie behind the conflicts around the world.

Published not long before the release in Britain of The Report of the Iraq Inquiry (the Chilcot report), it is a timely contribution. Recent attacks in France and Germany, and the ongoing catastrophes in Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Yemen, Libya and elsewhere, underline its relevance.

‘A wild decade of war and chaos’

Kilcullen begins by describing a crisis meeting in November 2014 in the United Arab Emirates. Representatives from the US, Britain, Iran, Russia, China, Gulf states and others attend sessions with titles like: ‘Syria and Iraq – In Search of a Strategy’; and ‘North Africa in Crisis’. Kilcullen says it felt like there was a huge geopolitical hangover, “after a wild decade of war and chaos”.

In May 2014, US president Barack Obama had given a speech at the military academy at West Point in which he did not mention the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (the Levant or, more narrowly, Syria) – ISIS. A fortnight later, ISIS seized Mosul, a city in northern Iraq with a population of two million. The pro-western government in Libya had collapsed and civil war erupted in Yemen. More than 2,000 mainly Palestinian people had been killed in the latest conflict with the Israeli state, Russia had annexed Crimea, and nine million Syrians were refugees. ISIS-inspired terrorists hit Europe, America, Africa, Australia and the Middle East: “Thirteen years, thousands of lives and billions of dollars after 9/11, any progress in the war on terrorism had seemingly been swept away in a matter of weeks”.

Kilcullen goes back to try to answer his own question: how did we end up here? As far as his own involvement was concerned, that began with the Bali bombing in October 2002 which killed 202 people, including 88 Australians. It was the first major operation by an Al-Qaeda affiliate since 9/11, when four coordinated attacks in the US cost the lives of 2,996 people. Bali triggered a reaction from the Australian government and Kilcullen got involved in early 2004, being seconded to the CIA in 2005.

Kilcullen held the view that, although the US/UK invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 had disrupted Al-Qaeda, led by Osama bin Laden, it had not been destroyed. As Al-Qaeda’s aim was to link (‘aggregate’) many disparate conflicts into a broad movement for ‘global jihad’, he reasoned, a strategy of ‘disaggregation’ was required: to break up the links.

From around 2005, this was an attempt to counter US president (2001-09) George W Bush’s ‘global war on terrorism’, which lumped the various groups and conflicts together, and implied that they all had to be fought at once. That, in turn, led to brutal excesses, such as CIA use of water-boarding and other forms of torture, and US/UK use of ‘extraordinary rendition’, where suspects were seized in one country and sent for interrogation in states like Syria (under Bashar al-Assad), Libya (then under Muammar Gaddafi) and Egypt (then under Hosni Mubarak). These extrajudicial practices, with their reliance on oppressive regimes, exposed the hypocrisy in claims by western capitalist powers that they were defending human rights and promoting democracy.

“Most egregiously”, writes Kilcullen, “the manipulation of intelligence to justify the invasion of Iraq – which had no known connection with 9/11 and turned out to have no current weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programmes – hugely undermined western credibility”. It actually reinforced the narrative of Al-Qaeda and other groups of a ‘war on Islam’.

Into Iraq

Right-wing neo-cons – such as US secretary of defence, Donald Rumsfeld, and vice-president, Dick Cheney – were dictating policy in the US administration. They were determined to restore US capitalism’s status and prestige, which had been dented by the 9/11 attacks. The lure of Iraq’s huge oil reserves were an additional, irresistible prize. And they were given full and internationally important political cover by Tony Blair’s New Labour government in Britain.

The neo-cons’ superiority complex was echoed by many on the left who felt that nothing could be done in the face of US imperialist might. A more far-sighted perspective, however, saw that the Iraq occupation was bound to unleash deep sectarian conflict and anti-western forces emanating from the Middle East. In addition, the general weakness of the global economy and the inevitable onset of capitalist economic crisis at some stage made the rise of class and mass struggle certain. In short, US invincibility was a temporary illusion.

Kilcullen writes that Rumsfeld “structured the invasion force in such a way that it had enough firepower to unseat Saddam Hussein but not enough manpower to ensure something stable would replace him”. Rumsfeld oversaw the disastrous ‘de-Baathification’ policy “that put 400,000 fighting men… out on the street with no future, homicidally intense grievances and all their weapons”, alongside hundreds of thousands of middle-class Iraqis who had been members of former dictator Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party as a condition for having a job.

The neo-cons consciously avoided detailed pre-war planning because it would have raised awkward questions over the financial and political costs of military intervention and ‘nation building’. Yet all the problems triggered by their war in Iraq had been predicted, and were communicated to US/UK establishment politicians. “I can’t recall one respectable expert in guerrilla warfare”, writes Kilcullen, “who didn’t predict… some version of the disaster that followed”. They were all ignored. “Bush and his aides were looking for intelligence not to guide their policy on Iraq but to market it. The intelligence would be the basis not for launching a war but for selling it”.

The invasion and occupation of Iraq set in train a series of crises which are nowhere near ending. One of the major weaknesses of Kilcullen’s analysis, however, is that he seems to think that the intractable problems can be resolved through tactical shifts and operational fixes: “It was impossible to get leaders to focus on resurgent violence in Afghanistan, the emergence of Al Shabaab in Somalia, the growing Pakistani Taliban, rising anti-terror cells in Europe, AQ franchises on other continents, or any of the other issues we could have addressed – and perhaps prevented – had the United States and its allies (including Australia and the UK) not been mired in Iraq”.

In reality, it is impossible to ‘disaggregate’ all these issues. Indeed, they have been ‘aggregated’ by the capitalist system itself. There are direct links between resource-rich neo-colonial countries, western-backed dictatorships continuing the divide-and-rule politics of former colonial masters, grinding mass poverty and rising anger and volatility. They can only be countered by a systemic alternative. Only a socialist system can plan the world’s resources democratically and sustainably – with mass participation in decision-making – ensuring cooperation and solidarity across borders to alleviate poverty and guarantee a future for all.

Post-invasion vacuum

Imperialist policy was creating the conditions for new anti-western forces to emerge, including Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s group, Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), later to become ISIS. As the conflict developed it became a proxy war between Iran, ruled by a Shia elite, and Sunni-establishment states, including Turkey and Saudi Arabia, as well as Israel.

Iraq was a mess. Sunnis had boycotted the January 2005 elections – turnout was 2% in Anbar province. Shia parties controlled the main ministries, bolstering their own wealth and political power. The interior ministry had its own torture chambers, and the health ministry used ambulances to transport arms to militias. Electricity and water supplies were denied to Sunni areas.

AQI fomented sectarian violence, only to pose as defenders of Sunni areas from the inevitable backlash from Shia militias. The level of violence was staggering and sickening. Hundreds of civilians were killed every week. Kidnapping gangs sold children for slaughter. Captives had drills driven into their brains. Makeshift studios made sectarian snuff videos.

By November 2006, the violence was out of control. Bush appointed General Petraeus to command in Iraq and the surge was launched. The stated aim was to back the counter-insurgency, push for a more inclusive Iraqi government, reduce civilian casualties and undermine AQI’s points of support. Kilcullen became Petraeus’s senior counter-insurgency adviser.

In June 2007, Sunni tribes rose up to fight AQI – the Anbar Awakening – a significant contribution to the surge. In July 2007, 2,693 civilians had been killed, in January 2009, 372. Viewed from a distance, governance seemed to be improving. Nonetheless, the ability to contain the violence was short-lived, based as it was on a massive, unsustainable mobilisation of US troops.

Kilcullen says that AQI had been “virtually destroyed” by the time Obama took office in January 2009. It still maintained a core, however, including former Hussein intelligence and special operations forces. Shia groups had not dispersed, either, but had merely accepted a ceasefire. They were still organised, armed and funded by Iran, biding their time. Obama replaced the global war on terrorism with ‘overseas contingency operations’. The use of drones was ramped up, alongside mass electronic surveillance and special forces raids.

Regional dictators fall

On 2 May 2011, a US Navy SEAL mission killed bin Laden in Pakistan. His death plunged Al-Qaeda into an internal crisis and it would take most of 2011 for Ayman al-Zawahiri to consolidate his authority. This meant that Al-Qaeda played no part in the early months of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ (which actually involved many peoples and ethnic groups) in Tunisia and Egypt. It was largely a bystander in the movement against Gaddafi in Libya and in the initial protests against Assad’s regime in Syria.

It had been a merger of the Afghan Services Bureau, led by bin Laden (who came from the Saudi big-business elite), and Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad which had set up Qa’idat al-Jihad (‘the base for jihad’), generally shortened to Al-Qaeda (‘the base’). Its leaders had been battle-hardened fighting against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan – where they received massive support from the US.

Kilcullen writes: “For 20 years bin Laden and Zawahiri had been telling ordinary people across the Middle East that they could never change their regimes through local (let alone peaceful or democratic) action, that the only solution was global jihadist terrorism against the super-power. In all that time, AQ had only managed to kill a few thousand Americans, while slaughtering a vastly greater number of Muslims and bringing about even stronger US engagement in the region. The Arab Spring thus contradicted AQ’s entire narrative”.

Yet Kilcullen, who looks at the world through battlefield binoculars – notwithstanding his invaluable military insight and knowledge of the situation on the ground – draws only the most superficial conclusion from this revolutionary upsurge: “Of all the countries that had experienced regime change during the initial wave of the Arab Spring, only Tunisia seemed – for the time being – to be progressing toward inclusive democracy. In general, judged in terms of its original aspirations, the Arab Spring was a failure”.

It is true that the movement has been derailed by a fierce counter-revolutionary onslaught. Nonetheless, what the events showed – in Tunisia and Egypt above all – was the potential power of the organised working class. In particular, it showed that mass struggle could overthrow brutal dictatorial rule. Despite the subsequent backlash, that is the key lesson learned. Moreover, to call the Arab Spring a failure is to imply that the movements have ended. The organised working class has not been defeated in Tunisia and Egypt and will re-embark on the road of struggle at some stage.

Reacting to sectarianism

In Syria, Assad cracked down hard on the mass movement against his regime. Islamic State in Iraq (ISI, which had changed its name from AQI in May 2010 under the leadership of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi) had a strong network in Syria. Baghdadi had taken over during the surge. As US troops began withdrawing, however, ISI was being strengthened with ex-Ba’ath Party personnel, who made up a third of its leadership by late 2010 – including military chief, Haji Bakr.

ISI restarted its attacks in Iraq – mainly against Shia police and officials, and assassinations of Sunni MPs and tribal leaders. Baghdadi also sent small groups of fighters to Syria in August 2011, then a more senior group under Bakr in late 2012. The relationship between ISI and Al-Qaeda was breaking down. According to Kilcullen, “Haji Bakr’s foray into Syria with the second groups of ISI cadres in late 2012 was, at least partly, designed to reinforce Baghdadi’s control over the increasingly autonomous Syrian faction”.

That faction was Jabhat al-Nusra (JN), led by Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, which also worked with other rebels, including the Free Syrian Army, backed by western powers. In April 2013, Baghdadi issued an ultimatum that JN had to publicly declare its membership of ISI. Instead, Jolani pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda’s leadership in Pakistan. Baghdadi then announced that ISI was now the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) – in open conflict with Al-Qaeda.

From January 2010, Iraqi prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, stepped up crude sectarian policies, disqualifying more than 500 candidates, mostly Sunni, from the March elections on the basis of previous Ba’ath Party connections. He cut funding to Sunni tribal elders fighting AQI and clamped down on the media. In December, he became defence, interior and prime minister.

These measures intensified in 2011. Hundreds of thousands of Sunnis staged Occupy-style protests across Anbar province in early 2012, and then across the country – against discrimination in jobs, services and pensions, the seizure of property, etc. In some areas, Shia joined these protests. In May 2013, Iraqi security forces destroyed a protest camp in Hawija, killing dozens of Sunni civilians. The massacre unleashed an uprising against Maliki.

Again, Kilcullen sees only one side of the process: “Maliki’s actions convinced many Sunnis of something AQI had been unable to persuade them of in 2006: that peaceful politics would never work, that armed struggle was the only route to survival”. There is, of course, some truth in that. However, for Kilcullen, there are only two options: either some pro-imperialist government is in place or sectarian bloodshed without end. The possibility that the working class and masses could be a factor is completely ignored – as though the revolutionary upheavals in 2011 had not happened!

Yet the example of Sunni mass protest attracting a section of Shia points to an alternative: a non-sectarian programme for jobs, homes, health, education and security, in opposition to repression and deadly division. That is not to say that it would be straightforward to advocate such a programme under those extremely difficult and dangerous conditions. Yet, even at that time of deep sectarian crisis, there had been a brief opportunity to develop support for that position.

Rise of IS

In January 2014, ISIS moved into Anbar province from Syria driving Iraqi forces out of Fallujah and Ramadi (capital of Anbar). It used a mix of guerrilla tactics and open warfare: “ISIS was thinking and fighting like a state: it had emerged from the shadows”. That statement is central to Kilcullen’s view on how to proceed. Kilcullen is not merely an observer. He participated in the development of the imperialist powers’ strategy, and he continues to influence capitalist establishment decision-makers. Kilcullen’s emphasis on ISIS as a state engaged in conventional warfare not only reflects reality. It also underpins his call for a new all-out offensive in the Middle East – with some tweaks in recognition of today’s altered political reality.

ISIS captured Mosul (capital of Nineveh) and other places by June 2014. Corruption, inadequate supplies and disorganisation – due to Maliki setting up a parallel command structure as insurance against coups – all played a part in the collapse of the Iraqi army and police. In addition, Shia security forces acted more like an army of occupation in Mosul, a predominantly Sunni and Kurdish city, and so lacked popular support. ISIS then took the strategically important city of Tikrit, the oil refinery town of Bayji and border crossings, giving it freedom of movement between Syria and Iraq.

On 29 June, ISIS announced its name-change to Islamic State (IS) and declared a caliphate with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as its head. Kilcullen comments: “… what happened in Iraq in mid-2014 was more than just a military defeat. It was the collapse of the entire post-Saddam social and political order…” Bush and Blair’s war had been a complete failure, their administrations responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, the descent into chaos of the region, and the exportation of terrorism around the world. They had been warned of the consequences – as both Kilcullen and the Chilcot report make clear.

Back into the quagmire

By mid-June the US re-established flying missions over Iraq and US combat troops were back in Baghdad. The UK, France, Canada, Australia and others were conducting airstrikes and sending in special forces, sucked back into the Iraq quagmire. France, the US and Gulf states bombed IS targets in Syria. In February 2015, Kurdish fighters backed by US airstrikes recaptured Kobani after a slow, brutal struggle.

The Iraqi government mobilised 30,000 Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF – Shia militia under the control of the interior ministry, notorious for ethnic cleansing of Sunni) and army troops against IS control of Tikrit, securing the city by mid-April. The Kurds stabilised the front west of Irbil. Then, IS recaptured Ramadi and took Palmyra, systematically subjugating the populations through mass public executions, torture and harsh repression. The loss of Ramadi further undermined the credibility of the central government, now under Haider al-Abadi, who had replaced Maliki in September 2014.

In Syria, Kilcullen reports that Jabhat al-Nusra was setting up command centres where rebel groups coordinated joint operations against the Assad regime. Rebels seized Idlib in northwest Syria, and moved against Aleppo and Latakia. The Southern Front was also advancing on Assad’s forces. A game-changer from Kilcullen’s point of view came on 14 July 2015 with the deal struck between the US, Russia and Iran over the Iranian state’s nuclear programme.

Many Syrian rebel forces (and Kilcullen) saw the deal as a sign that the US was outsourcing the anti-IS fight to Russia and Iran – and to Assad. Hezbollah completed this coalition. Saudi Arabia and Egypt set up a joint military force as a regional counter-balance to Iran. Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government in Turkey began creating ‘safe settlements’, with US support. Ostensibly for refugees, they acted against the newly-declared Kurdish statelet of Rojava.

A world of conflict

Kilcullen is despondent: “we’re facing a revival of great-power military competition in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, the Pacific and Europe that vastly complicates our options. Far from being coincidental, this too is a direct result of the way our failures in Iraq, in Afghanistan and in the broader war on terrorism since 2001 have telegraphed the limits of western power and showed adversaries exactly how to fight us… After 14 years, thousands of lives and hundreds of billions of dollars, we’re worse off today than before 9/11, with a stronger, more motivated, more dangerous enemy than ever”. This is “the new normal”. The only way intervention in other countries can work, Kilcullen states, is if it is linked to government reform, the ‘rule of law’ and economic development.

He says that would require something on the scale of the post-second world war Marshall Plan, including “more boots on the ground”. However, that war’s catastrophic destruction meant that infrastructure, whole cities, factories, roads and railways had to be rebuilt for capitalism to function again. Furthermore, the capitalist system faced an existential threat from a strengthened Soviet Union and Stalinist eastern bloc. As a result, huge resources were pumped in to reinforce social support for capitalism. An effort on such a colossal scale – especially in a world wracked with economic crisis – is inconceivable today.

Whether or not IS can be defeated militarily in the short- to medium-term is open to debate. It has shown itself capable of retreating to bases when under attack only to regroup and re-launch its offensives. Meanwhile, the horrific attacks perpetrated by IS members or inspired by them around the world over the last couple of years have added a new brutal dynamic.

In reality, IS is just the most vicious (so far) example of the consequences of imperialist invasion, occupation and intervention in the region. Russian and Iranian state backing for the Syrian and Iraqi regimes is echoed in greater support from Sunni states such as Saudi Arabia to right-wing political Islamists. This reinforces IS’s narrative of a sectarian war against the Sunnis. US/western powers’ anti-IS operations in parallel with Russia-Iran-Syria escalate the proxy wars and could even lead to direct clashes between the different blocs – which IS (or some spin-off or successor) could also exploit.

The capitalist system is based on the drive for profits. It involves a cut-throat struggle for the control of natural resources and strategic areas of the world. The Middle East – with its oil and gas reserves, colonial links with Britain and France, and with US neo-colonialism, as well as its position wedged between Europe, Asia and Africa – has long played an important geopolitical role. Imperialist intervention in this region, inevitably based on divide-and-rule and pacts with oppressive regimes, can only provoke and exacerbate sectarian division.

Kilcullen’s call for a “full-scale conventional campaign to destroy ISIS” really means more of the same. That is the new normal for capitalism today: a world of conflict, division, barbarity, economic crisis and poverty. That is the nightmare perspective on offer unless a way can be found to build the forces of socialism in the Middle East and around the world.

Be the first to comment