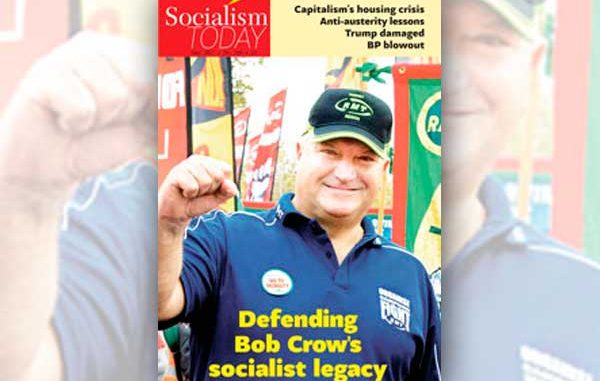

When Bob Crow died in March 2014 the trade union movement in Britain lost one of its best known and most determined fighters. He was far from being only an industrial militant, however. Bob was also instrumental in the struggle to build a new mass party of the working class, a key element underplayed in a new biography, ‘Bob Crow: socialist, leader, fighter – a political biography’ by Gregor Gall.

“They say you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone but in this case that is not true…” Non-RMT union members say: “I wish we had Bob Crow as our leader… we’d be a damn-sight better off… I wish I could join the RMT”. These remarks by Peter Pinkney, former president of the Rail Maritime and Transport union, following Bob Crow’s untimely death, are among the most pertinent in this book, indicating the support and deep affection for Bob from RMT members and militant workers everywhere. Gregor Gall details well his achievements on behalf of the union and its members on the industrial plane.

Bob Crow was strongly influenced by his working-class family, particularly his father, and in the world of work by the militancy of the RMT. The book also indicates that industrial action alone was not enough for rail workers because they also looked towards real political change. The RMT’s own rulebook and constitution (Clause 4b) pledges the union “to work for the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”. This runs like a red thread through the work of Bob and led him to the idea of a new mass working-class party after the betrayal of New Labour.

At 33-years-old, he was the youngest assistant general secretary in the RMT’s history. When he became general secretary he used the specific weight of the union to great advantage for its members. It was small in numbers but what it lacked in size was more than made up for by a fighting policy. It was also assisted by the role of railways as the arteries of industry and society. Small groups of RMT members could inflict serious dislocation through strike action sure in the knowledge that the union, particularly its general secretary, would support them.

Sometimes, as Gregor Gall shows, a lot was achieved without striking by the judicious use of democratically conducted ballots. Other union leaders appeared to use the same tactic, but often in an opposite sense – right-wingers wishing to reinforce their case that there was no ‘mood’ for industrial action! RMT ballots were generally held with energetic campaigns by the leadership for yes votes. The right-wing unions, in contrast, were invariably pessimistic about the chances of a serious struggle leading to victory.

The result was that, under the stewardship of Bob Crow and the left, quite spectacular results were achieved in driving up pay and improving conditions, including shorter hours, particularly when they involved RMT members in strategically-placed employment like the London Underground. A Guardian journalist asked him: “Is it true the drivers earn a basic £40,000? [Crow] looks at me, wide-eyed, as if he can’t quite believe the question. ‘Yeah! But we’ve got people on far more than that. Technical officers and signal workers are on £54,000. Basic. For a flat week. All pensionable’.”

The capitalist media sought to use this to whip up a hate campaign against ‘greedy’ RMT members. The author points out that some did succumb to vile propaganda: “post [the RMT] a turd”. But class conscious workers understand that if a union like the RMT – or the print workers in the past – achieved good conditions then this could become a benchmark for all of them leading to all boats rising together.

Moreover, there is no mechanism under capitalism – or any intention of the bosses – to funnel into the pockets of the low paid wages forgone by others. It just adds to their profits, a colossal cash pile. This bonus is not then reinvested back into industry, as the apologists for capitalism claim. It results in share buybacks which boost the value of shares, increased income for parasitic ‘coupon clippers’, and a massive inflation of CEOs’ salaries. The collective purchasing power of the working class is also cut, which in turn cuts the market resulting in unemployment, etc.

Gregor Gall, a professor of industrial relations, claims that this book is a political biography, and it does include some useful material about the industrial and political evolution of Bob Crow and the RMT. Judged by Gall’s own criterion, however, it is by no means a rounded-out or accurate description of Bob’s views on a number of crucial issues facing the labour movement during his lifetime and which still confront us today. In fact, it sometimes runs counter to how Bob’s ideas developed over a whole period and were evolving just before he died. This is particularly the case when examining his approach towards maximising the widest working-class and trade union opposition to the austerity-driven programme of Tory and earlier ‘Labour’ governments, as well as on the need for a new mass party of the working class.

Calling for a one-day general strike

Gregor Gall totally underestimates the potential that existed for mass coordinated strikes against the vicious austerity regime of Cameron-Clegg, including the possibility of general strike-type action. This was forcefully articulated to great acclaim by Bob Crow, together with other left-wing union leaders like Len McCluskey and Mark Serwotka, most notably in 2011-12 in front of mass assemblies of workers in Hyde Park and elsewhere. This was a clear demand made by the most authoritative left leaders in answer to the general attacks of the Con-Dem coalition, and specifically on the issues of an attack on hard-won pension rights and the cuts generally.

It was not taken any further at that stage because there was no coordinated pressure by the Trades Union Congress or, unfortunately, even from the left trade unions and their national executive committees. There was no consistent pressure to commit the general council of the TUC to prepare for at least a one-day general strike that could mobilise the full weight of the unions and the working class against the government.

Gall states that Bob Crow was mistaken in his call for a one-day general strike because the conditions were not present in 2011, or at any other time for that matter: “The deficiencies in Crow’s diagnosis and prognosis are attributable to a flawed understanding of the dynamics of popular rebellion”, which was also “true for other left-wing union leaders and the radical left. For Crow, as with others on the radical left… the subjectivity of hope trumped the objective test of reality”. Why? Because “the strikes of 2011-12 and July and October 2014 did not prove Crow right, since they represented the end and not the beginning of a fightback (and an unsuccessful one at that)”.

From the lofty heights of academia, Gregor Gall has put his thermometer under the tongue of lady history to conclude that the industrial and political temperature in Britain had not risen high enough for successful generalised action to stop the austerity government in its tracks. This pessimistic, fatalist philosophy – dear to the right wing of the trade unions – is sterile and a million miles removed from the real situation on the ground in 2011 and later.

The mood for a general strike does not drop from the sky. It is prepared for by the growing anger of the mass of the working class at the indignities which are piled on their shoulders. But to come to fruition a militant leadership is usually necessary, particularly in Britain, one which reinforces the idea of a general strike through relentless mass agitation and propaganda. The call for action is a dialogue, firstly with the more politically aware workers. Then the message has to be taken to the mass of trade unionists and workers. The preparation and implementation of a one-day strike are a means of testing out the mood, and were reflected in the tremendous public-sector strikes of that period.

Purveyors of pessimism

Anyone who participated in the strikes and demonstrations at this time witnessed the mood of anger and bitterness, but also the preparedness to take further action. What would be the character of follow-up action? Either a wider and better prepared one or two days of strikes which could, depending on the circumstances, have led to an all-out general strike at a certain stage. Of course, the purveyors of pessimism, the professors of gloom, decry such possibilities. Like Gall, they point to the ‘weaknesses’ of the membership of the official trade unions. This is what the so-called industrial experts have said on the eve of all gigantic mass movements and general strikes in the past, including Britain in 1926 and France 1968.

In France, the official tops of the unions said it was impossible to organise a general strike because, among other things, there was a parliamentary ‘dictatorship’ under president Charles de Gaulle, with armed guards in the factories and low trade union membership – even lower than in Britain today. At the time, we argued even with some Marxists and Trotskyists who dismissed the very idea of a generalised working-class uprising, which is what a general strike is. They said that working-class action was only possible in the distant future, taking the surface calm as an indication of quiescence on the part of the working class. It took a rebellion from below – with the students playing the role of the light cavalry of the revolution – to set the scene for the splendid movement of the French workers.

We were not taken unawares because we realised there was an ocean of discontent that had accumulated for more than ten years. This had prepared the ground for the eruption of the greatest general strike in history as ten million workers participated with factory occupations. At one stage the government fled France, with revolution in the air, only to be saved by the cowardly leaders of the ‘Communist’ Party and their equally frightened cousins in the leadership of the French Socialist Party.

Potential working class strength

There were elements of this under the Cameron-Clegg junta, although not on the same scale and under different historical circumstances. Even more so today, with the working class and poor besieged on all fronts: the lowest level of real wage growth for 200 years, savage attacks on the poor particularly the disabled and children, and the biggest housing crisis for decades with the number of homeless rising inexorably. A massive attack on conditions at work is also taking place, with an estimated 100,000 private hire drivers in London alone, including Uber, on slave wages helping to drive down the hard fought conditions of organised trade union drivers (as well as choking the arteries and the throats of Londoners through pollution).

Yes, trade union membership has decreased. But there are still six million organised – the biggest voluntary organisations in society – under the banner of the TUC. With the correct leadership they could act as a magnet for all the oppressed layers in a mighty display of working-class power. The formerly privileged, cushioned sections of the middle class, such as junior hospital doctors, under the hammer blows of capitalist crisis have been forced to adopt the methods of struggle of the working class: strikes, picket lines and protests.

Despite the urgings of the Socialist Party and its members in the trade unions, the support for a general strike was never carried through to a mass campaign within the union rank and file or on a broader plane. This hesitation applied to even the best left-wing leaders, never mind the right-wingers who systematically refuse to go outside the limits of the market (capitalism) and, therefore, end up as pawns of the bosses.

The right flank of the TUC – typified by Dave Prentis of Unison and others – was implacably opp-osed to even effective coordinated strike action to defeat the government on pensions and the cuts arising from the austerity regime of Cameron and Clegg. They preferred to ‘negotiate’ away the rights and conditions of their members, standing on the side-lines wringing their hands but doing nothing to stop the biggest attacks on the working class in generations.

Opposing militant industrial action, they had no effective counter-proposals other than looking towards a future austerity-lite Labour government to rescue them from the wicked Tories. Their inaction paved the way for further attacks, including worsening the already vicious anti-trade union legislation – the most draconian in the industrial world according to the International Labour Organisation. Further scandalous restrictions have been introduced on union elections, with trade union leaders expected to police picket lines, etc.

National Shop Stewards Network

Bob Crow was opposed to this approach and sought to create an effective weapon on the industrial and political planes to lay the basis for rolling back the employers’ and government’s attacks. Hence the setting up of the National Shop Stewards Network (NSSN) which Gall plays down in his book. This body, which has gathered the support of nine national unions, played a key role in popularising the idea of a general strike and organising to get it accepted by the labour movement. Working with the Prison Officers Association (POA), the RMT and other supportive unions, it organised to get a motion for the general strike on the TUC agenda in 2012 which, after debate, was passed!

Academic wiseacres might jib that the general council – particularly the right – never had any intention to implement the motion. After all, when the Pentonville dockers were jailed by the Tory government in 1972, the TUC committed itself to a general strike to force their release. However, this was only after it had been assured that the dockers were going to be freed anyway by the ‘official solicitor’, a kind of government fairy godmother! Yet the fact that the TUC passed the motion indicated the mass pressure that was being exerted. It is, moreover, of great symptomatic importance and is a precedent that will be returned to in the battles to come.

Gall states that the NSSN suffered from “problems of sectarianism… when in 2011 the NSSN suffered a split as a result of the Socialist Party majority insisting that the NSSN launch its own – and thus another – anti-cuts organisation… This occasioned criticism from Crow”. This is completely false. The NSSN majority did not want to set up a separate anti-cuts body, as the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP) falsely claimed when it split from the NSSN. There was no opposition to the idea of supporting anti-cuts campaigns.

The differences arose because the SWP and its allies wanted the NSSN to give a blank cheque to their front organisations, the Right to Work Campaign and the Coalition of Resistance. After Bob Crow had met the NSSN’s co-organiser Bill Mullins and its secretary Linda Taaffe, he was convinced of this and the RMT supported this position. Alex Gordon, then the RMT’s president, and Linda Taaffe made powerful speeches in opposition to the SWP and its allies, and won an overwhelming majority at the 2011 NSSN conference.

Gregor Gall is not an independent observer, as he likes to pretend. In this conflict he was an ally of the NSSN’s former chairperson Dave Chapple, who subsequently split and plays no important role in the unions today. We wanted to provide an effective voice for the working class and were prepared to work in an alliance, a united front, with all those who were prepared to struggle, while retaining full freedom to criticise. So did Bob Crow who found that the Socialist Party was more open than any other organisation to this approach.

Despite himself, even Gall recognises the close affinity between the Socialist Party and Bob Crow: “Crow identified more with the Socialist Party than any other party once he became general secretary. In addition to his involvement with TUSC, he spurned the Convention of the Left initiative of the late 2000s (unlike Serwotka and Wrack).”

But the deep class loyalty of Bob Crow, and his positive approach in reaching out to others like the Socialist Party in order to push the movement forward, is not enough for the author, who implies criticism without clearly spelling it out. Gall resorts to abstruse academic sleight of hand: “Critical Marxism also means not taking things at face value just because they came from a ‘communist/socialist’. It means avoiding the ‘spin’ that Crow and the RMT put on the battles they fought… There is a dynamic, osmotic relationship between leaders and followers comprising the person, position, process and outcome”.

For a new workers’ party

Gall includes many one-sided assertions of Bob Crow’s views on socialism, which were not settled. It is claimed that he had a ‘statist’, top-down approach. The truth is that Crow was re-evaluating and searching for answers as many were in the aftermath of the collapse of Stalinism. This is actually shown by Gall when he quotes Crow: “I’ve never seen a true communist state, so I don’t know whether it would work… I don’t think communism has failed – the problem was the lack of democracy. They had far better hospitals, far better education. I went to Cuba and they may not have had satellite dishes or DVD players, but they had a doctor on every corner, they had good schools, the basic fundamentals in life were far better than they are here. If the communist regimes had got more people involved in democratic decisions, they would still be there now”.

We, like Bob Crow, prefer plain speaking to academic jargon. Bob did make some mistakes, was unnecessarily hesitant at times, for instance on the timing and character of a new party. Like Arthur Scargill he supported the idea of a new party but did not immediately recognise the need for a federal form of organisation for its success. In fact, it was the Socialist Party which pioneered both the idea of a new party and the necessity for a federation. But under the pressure of the situation, his own members and the working class generally, Bob met our representatives, proposing that we join with them in a new party, the Socialist Labour Party (SLP). There was a condition, however: that we abandon our newspaper and organisation! We deal with this in our new book on the Socialist Party’s history to be published shortly. We rejected Scargill and the SLP’s sectarianism – as did Bob Crow later – which ultimately led to the SLP’s collapse and to Crow leaving that party.

Bob did not then sulk or throw in the towel. He learnt from it and continued to press for the setting up of a new political formation to replace discredited New Labour. This laid the basis, after a series of false starts, for the establishment of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). Gregor Gall’s prejudice towards the Socialist Party is evident throughout as he consistently underestimates the effect that we had on Bob, and he on us. Even in the abbreviations at the front of the book he cannot bring himself to include the Socialist Party. Most other left organisations are mentioned, many much less influential.

Gall informs us that he did not receive “official RMT cooperation… because the union acceded to a request from Crow’s family not to cooperate with any biography that had not been commissioned by them”. Not surprisingly, in view of the distortions and criticisms of Bob Crow’s real views! In this sense, the book is like the curate’s egg: good in parts but in others not so good and even bad. The enduring legacy of Bob Crow is evident today. Peter Pinkney told the 2015 TUSC conference: “TUSC is not dead and we’re not reaffilliating to the Labour Party. What if Jeremy’s ousted in six months and the right-wingers are back in charge? We’ll continue to support TUSC – and wait and see on the Labour Party”.

Disaffiliating from Labour

This does not prevent Gall from disputing that this reflected a growing level of political consciousness among rail workers. Nonetheless, he is forced to indicate that this aspiration for socialism is still reflected in the RMT’s rulebook even while New Labour moved towards the right: “Under the continued disillusionment with ‘new’ Labour from 1994 and then after leaving Labour in 2004, the RMT spoke and acted in the political field almost as its own party because of Labour’s simultaneous rejection of social democracy and embrace of neoliberalism… That led to the RMT’s involvement in helping to attempt to establish a new socialist party”.

Moreover, he indicates the RMT’s growing discontent with Labour’s pro-big business policies: “In 1998, its AGM voted narrowly against disaffiliation by 27 votes to 21 but it began reducing the funding it gave Labour and the number of members it affiliated… [In 2001 the RMT] voted to withdraw funding from those sponsored MPs who did not back rail renationalisation”. This was even before Bob Crow became general secretary. Crow said: “We’ve supported the Labour Party but we’re going to investigate what MPs are fighting for us – and some aren’t. If they want to be sponsored, they’ve got to be seen rolling their sleeves up and fighting for us… We deserve at least one meeting and a cup of tea [with them]. If they want our money, they have to roll their sleeves up and fight as hard as I do for the renationalisation of rail”.

Gall details well the process which preceded disaffiliation from the Labour Party. Writing in the New Statesman, Peter Hain MP said that Bob was a splitter and a saboteur: “Don’t let Tories and Trots crow”. Bob Crow responded by pointing to his opposition in the early 2000s to disaffiliation from the Labour Party which he expressed at the RMT’s annual general meeting and also at the 2002 conference of the Socialist Campaign Group. Bob gave notice at the following year’s AGM that disaffiliation would be debated. In this sense, he was reflecting the gradual and growing opposition to the move towards the right of Labour under the whip of Blairism, which in turn also reflected the growing crisis of British capitalism.

As with British workers in general, Bob Crow – although always a committed socialist – adopted an empirical, gradual approach towards disaffiliation from the Labour Party. He was also conscious of the need to take his union members with him, the more politically developed and other layers, on such a serious issue as disaffiliation from the party the union helped found 100 years before.

Gregor Gall’s book gives some of the explanation, though not all, of why Bob Crow made such an impact during his life. His work, however, is not done. The civil war within the Labour Party continues apace. The right wing must be defeated and ejected through mandatory reselection and the struggle for political clarity. Only when a mass party with clear socialist policies is in place will we be able to say that Bob Crow’s work has been carried out.

‘Bob Crow: socialist, leader, fighter – a political biography’, By Gregor Gall (Published by Manchester University Press, 2017, £20)

Be the first to comment