The tenth of April 2018 marks the twentieth anniversary of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in Belfast. This was the formal ending of the ‘Troubles’, the euphemism for decades of sectarian upheaval and armed conflict that wracked the north of Ireland.

Key figures involved in the negotiations that produced the GFA, such as Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams, the Ulster Unionist Party’s David Trimble, former US president Bill Clinton and former prime minister Tony Blair, are due to congregate in Belfast to celebrate the ‘model peace process’. But given that Northern Ireland’s power-sharing executive remains collapsed, the festivities will be conducted with some embarrassment and even despair.

Months of deadlock between the former governing parties, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fein, underlines the fact that the agreement never lived up to its billing as bringing long-term peace, stability and prosperity to Northern Ireland. Twenty years since its implementation, the GFA stands on the brink, with its definitive breakdown potentially on the cards.

The establishment’s narrative is that the 1998 agreement brought to an end a seemingly irrational tribal war. However, when the Northern Ireland civil rights’ movement exploded onto the scene 50 years ago, it attracted not just mass support from Catholics but also initially layers of Protestant youth.

Socialist leadership

With a determined socialist leadership, the possibility existed of fundamental change. But as sectarian bigots and nationalist and unionist political parties attempted to sow divisions among workers and to derail the movement, the labour and trade union leaders failed to present a class alternative.

Due to anger at brutal state repression and deep frustration at the failure of ‘politics’ to end discrimination and poverty, many working class Catholic youth turned to the Official and Provisional IRA in the early 1970s.

From the start, the Socialist Party (CWI Ireland) and its predecessor Militant argued that the republican armed campaigns would prove counterproductive, dividing the working class further and failing to defeat the might of the British state while providing it with the justification to increase repression.

At the same time, Loyalist paramilitaries carried out indiscriminate, deadly attacks against innocent Catholics.

In conditions of daily bombings and shootings, heavy state repression and polarisation, those, like Militant, advocating for the unions to resist sectarianism and repression, to organise the defence of working class communities and to build a workers’ political alternative, often seemed like lone voices.

Nevertheless, Catholic and Protestant workers remained united in shared workplaces and in the unions. Not one strike was broken by sectarianism, despite the best efforts of bigots on both sides.

By the 1980s the IRA’s campaign had run out of momentum. While the British state could not defeat the IRA, it was able to contain the Provisional IRA’s campaign with military means and intelligence.

During the 1990s many on the left were also disorientated by the developing ‘peace process’ in Ireland and the role of Sinn Fein. The Gerry Adams/Martin McGuinness leadership wanted to cut a ‘power-sharing’ deal in the North, without achieving their long-stated goal of immediate British withdrawal and a united Ireland. In the 20 years since, they have accommodated themselves to administering capitalist austerity in the power-sharing executive.

All sides had to make significant compromises to reach a deal. Prisoner releases, paramilitary arms ‘decommissioning’ and British ‘demilitarisation’ were just some of the highly contentious issues that took years to carry out.

The GFA also enshrined the ending of institutionalised discrimination – a process already underway largely as a result of working class Catholics’ implacable opposition to a return to any form of Unionist misrule.

Capitalist status quo

But it was Sinn Fein that gave most ground leading up to the signing of the GFA in 1998. The collapse of the Stalinist regimes in Russia and Eastern Europe sped up the process of movements like the ANC in South Africa, PLO in Palestine and the IRA coming to terms with the capitalist status quo.

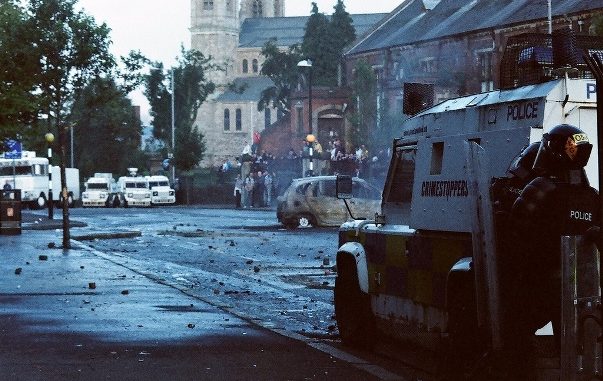

In the North, after two decades of conflict, and apparent military stalemate, there was also ‘war weariness’ on all sides. Between 1969 and 1998, some 3,289 people were killed as a result of the conflict – the equivalent ratio of victims to population in Britain would have seen 100,000 people killed.

The Sunningdale Agreement of 1973 – whose main provisions were very similar to that of the GFA – had proved unpalatable to the “extremes” (Ian Paisley’s DUP and loyalist groups, whose ‘Ulster stoppage’ brought Sunningdale crashing down, and the Provisional IRA who denounced it as a “partitionist” sell-out). But twenty five further years of sectarian deadlock, paramilitary campaigns and state repression, as well as rejection of violence by the working class, forced an agreement.

Establishment politicians perpetuate the myth that ‘peace’ in the 1990s was achieved largely from above. But the yearning for an end to the conflict was expressed most forcibly and consistently from below. This was indicated by the Socialist Party’s slogan, ‘No going back!’ which caught the imagination of many working class people.

As paramilitary organisations moved towards shaky ceasefires, many thousands of Catholic and Protestant workers went on protests – often initiated by Militant/Socialist Party supporters in trades councils and unions – against a slide back to sectarian conflict. And the party’s initiative, Youth Against Sectarianism, rallied thousands of school students from both sides of the divide across the North.

We pointed out that the peace process and GFA would not bring about lasting peace and prosperity, as many claimed. It institutionalised sectarianism, including with the stipulation that Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) officially state they are ‘nationalist’ or ‘unionist’ or ‘other’.

Nevertheless, the Socialist Party called for a critical ‘yes’ vote during the referendum held on the GFA, North and South. Relative peace would, at least, give the working class a much better opportunity to develop class politics.

From the start, the institutions created by GFA were beset by instability and crisis. Events on the ground, such as disputes over parades, threatened to bring down the power-sharing executive. After a suspension of the assembly, a new deal, the St Andrews Agreement, was painfully put together to restore power-sharing in May 2007.

Rather than bringing the two communities together, the institutionalisation of sectarianism led to the opposite extremes of the political spectrum, the DUP and Sinn Fein, supplanting the ‘moderate’ nationalist and unionist parties.

The decade of power-sharing rule of these two parties saw an intensification of the policies of privatisation, education cuts, health cuts and a failed attempt to impose water charges. While content to work together carrying out Tory government austerity cuts, the DUP and Sinn Fein conducted sectarian mud-slinging against one another on outstanding Troubles-related issues. This also served the useful purpose of averting attention away from their unpopular policies and to bolster their sectarian support.

For many of their voters, however, the power-sharing relationship produced no ‘peace dividend’. Over 25% of children live in poverty, public services are slashed, miles of ‘peace walls’ still divide Catholic and Protestant working class communities, and basic rights, such as same-sex marriage and a woman’s right to choose (which both Sinn Fein and the DUP oppose) are denied.

‘Cash for ash’

Scandals and sleaze surrounded the executive. The DUP leadership was embroiled in the Renewable Heat Incentive ‘cash for ash’ scandal that could squander up to £700 million of public money for the benefit of their big businesses friends. Sinn Fein was slow to take up this scandal and it was only widespread anger among Catholics that forced the party to call time on power sharing.

Since the collapse of the executive, new factors, such as Brexit, have destabilised the situation further. All the parties oppose a return to a ‘hard border’. Not only would it most likely lead to economic dislocation but it would present a powerful propaganda weapon to republican dissidents.

The Tory government advocates a free trade deal with the EU or a ‘high tech customs system’ that does not require a hard border. Quite how this can work, with over 200 border crossings, remains to be seen.

Theresa May acquiesced to the EU demand for a ‘backstop’ arrangement which would somehow keep Northern Ireland in the Customs Union if no other option can be found. Although what the backstop entails is left purposefully ambiguous. The DUP, supported by the pro-Brexit faction of the Tory party, would fiercely oppose any ‘exceptionalism’ for Northern Ireland.

In this fraught atmosphere, Sinn Fein campaigns for a ‘border poll’. Gerry Adams blithely comments, “the Good Friday Agreement… allows for Irish reunification in the context of a democratic vote: 50% plus one.”

Lurking behind the concrete issues of controversy in the current crisis are factors and changes of greater magnitude and impact, such as the demographic shift taking place, with Catholics set to become a majority in Northern Ireland in the near future. This threatens one of the pillars – an in-built Protestant majority – of the state’s very foundation, underlining the instability and fragility of the Good Friday Agreement.

Northern Catholics have long held valid national aspirations and, of course, have a right to decide their future. But Sinn Fein’s crude ‘majoritarianism’ will not deliver the peaceful, stable, prosperous united Ireland they yearn for.

Sinn Fein dismisses genuine Protestant working class fears of becoming second-class citizens in a capitalist united Ireland and the fierce reaction to moves towards it.

Dublin-based commentator Fintan O’Toole argued in the Irish Times that it cannot be assumed that southerners, who must also hold a referendum to decide the border, will vote “…for a form of unity that merely creates an angry and alienated Protestant minority within a bitterly contested new state”.

Two decades on, the Good Friday Agreement’s institutions are suspended and its provisions, based on the assumption of endless sectarianism, only aggravate divisions. In many ways, we see a continuation of the Troubles “by other means”, like the sharply contentious question of implementing an Irish Language Act.

And the GFA has not brought universal peace and justice. Low-level paramilitary attacks and punishment beatings continue in many deprived areas, as does British state repression.

The DUP’s leader, Arlene Foster, calls for a period of direct rule from London. This is strongly opposed by nationalists, especially as her party props up the Tories. They call for a period of ‘joint direct rule’ between London and Dublin, which, in turn, is vehemently opposed by Unionists.

It is more likely that the current situation, a ‘light’ form of direct rule, will continue for some time before the British and Irish governments attempt another deal, a St Andrews Agreement Mark 2.

None of this resembles the peace, stability and prosperity promised 20 years ago. An absence of a deal opens up a dangerous vacuum on the ground. And any restored power-sharing executive will only be on the basis of unprincipled fudges on many issues, preparing the way for more instability and crisis.

United working class

Only a united working class struggle, with socialist policies, can show a way out of austerity, poverty, injustice, and sectarian divisions.

Genuine ‘power-sharing’ from a socialist perspective entails working class people, Catholic and Protestant, coming together to democratically agree on new arrangements. A socialist society, based on people’s needs, would see the ending of all coercion against either of the communities, overcoming historic fears and distrust.

This is the power-sharing solution – the basis for a new, socialist Ireland – that the workers’ movement should take up in Ireland and Britain, linking it to a voluntary, equal socialist federation of these islands and Europe.

[The author was Chair of Youth Against Sectarianism, Northern Ireland, and a member of the Socialist Party, in Belfast, during the 1990s]

Be the first to comment