Although violence has remained at a relatively low level in Northern Ireland since the ending of the ‘Troubles’, the recent killing of the young journalist, Lyra McKee, in Derry city, by a republican armed group, caused shock waves of revulsion. This took place with the background of fears of a possible Brexit-imposed ‘hard border’ and ongoing austerity stoking tensions. Niall Mulholland reviews a new book looking at dissident republican groups, ‘Unfinished Business: the politics of ‘dissident’ Irish republicanism’.

In August 1994, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) declared an unconditional ceasefire. This followed a generation of bloody conflict in Northern Ireland, whose other main combatants were British state forces and loyalist paramilitaries. At the time, Sinn Féin president, Gerry Adams, claimed some sort of victory for the IRA. In truth, after 25 years, the armed conflict was at a stalemate. The IRA had failed in its declared aim of driving out the British army and achieving the unification of Ireland, while state repression was unable to completely defeat the IRA.

After the cessation of the armed campaign, years of torturous peace talks led to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Sinn Féin then did what was unthinkable to many. It took up seats in the new Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly, joined the policing board of the new Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), endorsed the ‘consent principle’ (Protestant consent to a united Ireland), and shared power with the hard-line Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

In rationalising this departure from its long-held aims and methods, Sinn Féin claimed that the IRA campaign was the cutting edge of a long republican struggle, forcing the British to the negotiating table and winning an ‘equality agenda’ for Catholics. Sinn Féin argued that equality within the North would form a stepping stone towards Irish unity.

Republican ‘dissidents’, the subject of Marisa McGlinchey’s book, reject the Provisionals’ narrative. They “assert their belief that altered structural conditions within the North of Ireland do not impact on republican ideology or activism”. They “label altered conditions as ‘reform’ rather than ‘radical change’, rejecting the ‘normalisation’ of the state of Northern Ireland”. Kevin Hannaway, a former adjutant-general of the PIRA and a first cousin of Gerry Adams, tells McGlinchey: “The present leadership of Sinn Féin – if they were out for an Irish Republic they failed. If they were out for civil rights they got it in 1973. So what the fucking hell was the other thirty years of war for?”

Major points where republican groups broke away from the Provisional movement were the 1986 decision to end abstentionism to the Southern Ireland parliament, the 1994 and 1997 ceasefires, the Good Friday Agreement, the decommissioning of IRA arms in 2005, Sinn Féin’s acceptance of the PSNI in 2007, and its leader and former IRA head, Martin McGuinness, shaking hands with the British Queen in 2012.

Republican contradictions

By the lights of their republican ideology, the dissidents (or ‘non-mainstream’ and ‘radical’ republicans, as McGlinchey also refers to them) have valid criticisms of Sinn Féin. Sinn Féin has departed from the traditional core principles of the republican movement. For 25 years, the PIRA and Sinn Féin repeated that its aims were a united Ireland, the withdrawal of the British army and the abolition of the ‘unionist veto’.

But their analysis of why the Provisional movement ended up ‘selling out’ is fundamentally flawed. It also explains why they are “fraught with division regarding strategy” today, according to McGlinchey, who interviewed nearly 100 figures from the “radical republican family”. Written in a scholarly manner, Unfinished Business provides a comprehensive summary of their views. The republican movement has always been a broad church, from right-wing, Catholic, pro-capitalist wings to radical left-republicanism.

The late Tony Catney, a member of the 1916 Societies in Belfast, commented on the current non-mainstream movement: “There are people I know who are involved in republican struggle and their politics are as right wing as Maggie Thatcher ever was. They just want to be right-wing Irish rather than right-wing English”. At the same time, Nathan Hastings, who is affiliated with Saoradh (Liberation) formed in 2016, says there is a need for a republican organisation “which is scientifically socialist along Marxist and Leninist lines”. Several republican groups, like Éirígí (Rise Up), reject Sinn Féin’s ‘highly centralised’, ‘authoritarian’ structures, and adopt a ‘flat structure’ around branch ‘circles’.

These contradictory views have existed for many decades within Irish republicanism. At root, they reflect the contrasting working-class, middle-class and even bourgeois backgrounds of republicans. However, all variants of republicanism have failed to reach their objectives, something inextricably linked to the flawed analysis. But why bother with what Sinn Féin dismisses as ‘micro-groups’ and ‘criminal gangs’?

While the forces of traditional republicanism are much reduced, neither are they negligible. It would be mistaken to think they cannot grow, particularly if the workers’ movement fails to provide a clear socialist alternative. Dissident republicans can make inroads among Catholic youth in the North, alienated from the ‘establishment’ Sinn Féin and with no experience of any meaningful peace dividend. Continual state repression in many working-class Catholic areas including, in effect, internment without trial of dissident suspects, is also a running sore that can lead youth to embrace armed struggle.

Rising against British imperialism

A Marxist analysis of the national question in Ireland and the physical-force tradition of republicanism must start by laying the blame for the country’s centuries-long agony at the feet of colonialism and British imperialism. Brutal oppression and injustice led to many uprisings. With the development of capitalism and the working class in the 19th century, Leon Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution was borne out in Ireland. This held that the capitalist class in the modern epoch is incapable of solving the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution.

In the case of colonial countries, that means first and foremost the struggle for national emancipation. All the heroic struggles of the Irish people were betrayed by bourgeois nationalist leaders. At each stage, the national question was inextricably linked to social problems. The national emancipation of the Irish people could only be won through the emancipation of the working class, which has no interest in any form of national or religious oppression.

The ideas of the permanent revolution were echoed by the great Irish workers’ leader and socialist, James Connolly. He wrote: “If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin castle, unless you set about the organisation of the socialist republic your efforts will be in vain. England will still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country”.

During the first world war, the Irish bourgeois nationalist leaders in the Westminster parliament, enticed with the promise of home rule for Ireland, supported the imperialist slaughter and encouraged Irish volunteers to the front. However, this prepared the way for the 1916 Easter rising. Connolly’s workers’ militia, the Irish Citizen Army, joined forces with petit-bourgeois republicans to stage the uprising, which was put down with terrible savagery by the British army. This provoked mass revulsion and laid the basis for the ‘war of independence’ from 1919-21.

After Connolly’s execution, Irish labour leaders submitted to Sinn Féin’s dictum that ‘Labour must wait’. They handed over the leadership of the anti-imperialist struggle to middle-class nationalism. The potential for socialist revolution was lost and the movement ended in partition and defeat for the working class. “A carnival of reaction both North and South”, as Connolly had correctly predicted, set back the Irish labour movement.

Voting for unity?

Today’s radical republicans claim that their legitimacy lies in “the thirty-two county Irish republic, proclaimed by rebels at the steps of the GPO in Dublin 1916 and established by the First Dáil Eireann (Irish parliament) in 1919”. This abstract position takes no account of the big changes in Irish society since 1919, not least the creation of two states and entrenched sectarian divisions in the North.

Marxists consider imperialist partition a monstrous crime against the working class of the island. Nevertheless, we need to take into account the changes it wrought when putting forward a pro-working-class, socialist solution to the national and sectarian divisions. If the Provos’ decades-long armed campaign could not convince Protestants of the wisdom of becoming part of a united Ireland, how can the myriad of much smaller non-mainstream republicans do so today?

Divisions exist among republicans on how ‘sovereignty’ should be exercised. In 2012, the 1916 Societies launched a One Ireland One Vote (OIOV) campaign, which claims to advance the strategy of an all-Ireland vote on unity. This was partly in response to Sinn Féin’s call for a border poll referendum in Northern Ireland on uniting Ireland. During the June 2017 Westminster election debate, the leader of Sinn Féin in the North, Michelle O’Neill, playing on the genuine national aspirations and democratic sentiments of Catholics, made a border poll central to the party’s political strategy. She argued that Brexit had “fundamentally altered the context”.

Without a hint of irony, Tony Catney pointed out the problems: “Even if people in the six counties vote yes the triple lock kicks in… The border poll is a sectarian head count. Republicanism is non-sectarian”. But why would Protestants be any more open to an all-Ireland vote? It is not the formal methods of voting that lie behind Protestant opposition. It is the fear of being forced against their will, by bomb or ballot, into a united Ireland. Protestant working-class fears of being a discriminated against minority under the capitalism system are real. They fear their distinct sense of identity and community coming under assault.

Britain’s attitude to Ireland

Radical republicans vehemently oppose Sinn Féin’s acceptance of the consent principle, regarding it as acceptance of a unionist veto to prevent a united Ireland. But the historically deterministic mandate claimed is, at best, woefully dismissive of Protestant desires and fears. At worst, it is a sectarian approach. In part, it arises from a fundamentally wrong analysis about the intentions of British imperialism. During the ‘Troubles’, the republican movement’s main demand was British withdrawal. Yet Britain’s ruling class had long wanted to leave Ireland but Protestant opposition and the threat of civil war blocked this path. This flawed analysis is repeated by the dissident or non-mainstream republicans today.

At the time of partition, British imperialism sought to keep the northeast of Ireland, the most industrialised and militarily strategic region, with the rest of the UK. After the second world war, however, that changed. With the advent of nuclear arms, the strategic importance of the northeast greatly lessened. Northern Ireland, the poorest part of the UK, was also a major drain on the exchequer.

The British ruling elite would have liked to have got rid of the ‘Ulster problem’ while still exploiting its working class and resources. But it was weighed down by the resistance of Protestants to any serious moves towards a capitalist united Ireland. The ruling class had fostered sectarian divisions within the North for decades and now found they were not so easy to undo.

As the interviewees concede in Unfinished Business, the IRA’s armed campaigns from partition until 1969 were sporadic and lacked popular support. The 1956-62 border campaign was ended, McGlinchey writes, because of “low morale, low public support and a campaign which could not be sustained”. In fact, IRA campaigns were sideshows to the class battles that erupted in the North, once the working class began to recover from the historic setback of partition. This included the 1932 outdoor relief strike of unemployed Protestant and Catholic workers, and a big increase in industrial disputes in the 1960s.

Sending the troops in

The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) grew, reaching a peak in the 1960s, increasingly becoming a threat to the right-wing Ulster Unionist Party and Nationalist Party. The mass civil rights movement, which exploded in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s, was inspired by international events, including the US black civil rights struggle, the anti-Vietnam war movement, and the revolutionary May 1968 events in France. However, the tops of the NILP and trade unions were dominated by the right wing and failed to give workers an independent class lead.

At the same time, socialist currents in the movement were not strong enough to stop the drift towards sectarian conflict. Right-wing nationalist leaders like John Hume were able to dominate the civil rights struggle, giving it a ‘green’ colour. Meanwhile, arch-bigots like Ian Paisley played on Protestant fears that Catholics would win rights at ‘their expense’. The situation deteriorated into serious sectarian conflict in Belfast and other areas. In August 1969, the Westminster Labour government put British troops on the streets.

Militant in Ireland and in Britain (forerunners of the Socialist Parties in Ireland, and England and Wales, both part of the CWI), opposed the deployment of troops. We warned that, primarily, they were there to defend private property and capitalist interests. British soldiers would soon be used against the Catholic minority fighting for democratic and social rights.

The IRA’s failure to defend Catholic areas in Belfast against sectarian pogroms led to a split in its small organisation at the end of 1969 – between the Officials and the Provisionals, who were more nationalist and militaristic. The Southern Fianna Fáil government backed the Provisionals against the ‘Marxist-influenced’ Officials. Initially, just a trickle of new recruits joined the Provisionals but vicious British army repression turned this into a torrent. Poverty, discrimination and state repression, including internment without trial and Bloody Sunday, drove working-class Catholic youth into the IRA.

During this time, there were widespread illusions in Catholic areas that the Provos could drive out British imperialism and unify the country. Many on the left compounded this mistaken belief by acting as cheerleaders for the IRA’s campaign. From the beginning, however, Militant opposed the Provos’ armed struggle because it could not succeed and would be counterproductive. Although described as ‘guerrillaism’, taking place in a developed and largely urban society, it was individual terrorism – isolated military actions carried out by small groups. The IRA’s actions gave the British state the excuse to introduce repressive legislation and methods.

Provos ‘compromised’?

This secret army or elite, acting ‘on behalf’ of the oppressed, would never succeed in defeating the might of the British state and overthrowing capitalism. The task of ending capitalism and transforming society falls to the working class, using mass struggle, including demonstrations, strikes, civil disobedience, general strikes and, ultimately, insurrection. The IRA’s campaign was based on the Catholic minority and completely repelled Protestants. This divided and weakened the working class and so strengthened the ruling class.

For dissident republicans, the failure of the Provos’ campaign was just a matter of leadership. McGlinchey concludes: “A common thread of thought throughout radical groups and independents is that the Provisional IRA was ‘compromised’. Repeated revelations regarding British agents in the IRA have added weight to this thesis among radical republicans who believe that the campaign itself did not fail; rather the Provisional leadership failed. The promotion of this narrative throughout radical republican circles illustrates why current groups feel they can succeed where the Provisional campaign failed”.

Dissident republicans believe there was an overall plan being pursued by some within the leadership to “wind down the Provisional movement and to pursue the path which the party is now on, which radical republicans would at best describe as constitutional nationalism”. Through infiltrating the Provos, the “state could better judge accurately what kind of compromise was necessary and achievable to bring the vast majority of republicans into a future without the IRA”.

The British state undoubtedly infiltrated the Provisional movement, at various levels. But this alone did not lead to the Provos’ ceasefires and Sinn Féin signing the Good Friday Agreement. Whatever degree of success British state agents had inside the Provisional movement in directing policy could only be based on much stronger objective and subjective factors.

Looking for a way out

The initial upsurge in IRA activity in the early 1970s, when the leadership predicted imminent victory, gave way to ‘the long war’. While the IRA could not defeat the might of British imperialism, the state could not totally defeat it. Poverty, repression and injustice meant there were always new recruits.

Sinn Féin’s rise as an electoral force, following the 1981 hunger strikes, created tensions within the republican movement. The Adams leadership hoped Sinn Féin could make a breakthrough North and South. But the IRA’s campaign was a barrier to Sinn Féin’s growth, especially in the South. Former IRA prisoner, Tommy McKearney, noted that “by the end of the 1970s, the IRA was finding it more difficult to win supporters in the Republic of Ireland”. McGlinchey adds: “Sinn Féin’s ‘armalite and ballot box’ maintained a glass ceiling on support for the party which could only be removed through the ending of the Provisionals’ armed campaign”.

By the late 1980s, Sinn Féin’s leadership was looking for a way out. War-weariness among Catholics and Protestants, the feeling that neither side could win outright victory, and working-class opposition to sectarian killings, formed the backdrop to the eventual ending of the Provos’ campaign in the 1990s. The republican leadership was also influenced by world events, including the shift to the right by other ‘national liberation’ struggles, like the ANC, following the collapse of Stalinist regimes in Russia and eastern Europe, and the supposed triumph of the market economy.

Talks between Sinn Féin and the British and Irish governments, backed by the US administration, eventually led to the IRA’s ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement. In the absence of the divisive armed campaign, the party made big advances in elections across Ireland. Sinn Féin eventually supplanted the nationalist, middle-class SDLP to become the largest party among Northern Catholics. It presented itself as a radical, anti-establishment party that won gains for Catholics with its ‘equality agenda’.

Long gone is even a serious attempt at a veneer of socialism. Martin Og Meehan, a former Sinn Féin member, commented: “I voted yes for the Good Friday Agreement but Sinn Féin aren’t going anywhere and the socialist republic has vanished from the vocabulary of Sinn Féin”. He goes on: “I was deluded into believing that it [the GFA] was a transitional arrangement and that there would be a massive peace dividend for working-class communities in the Six Counties”.

Potential for renewed conflict

Sinn Féin is a sectarian-based party. They “have now come to be the representatives of the Catholic population”, Tommy McKearney concludes. In the assembly, it carried out pro-market policies, including austerity cuts, along with its coalition partners, the DUP. The main problem for the non-mainstream republicans, however, is their lack of a viable alternative.

They are also disunited on key aspects of republicanism, such as whether to stand for election to Leinster House (the parliament building in Dublin) and take seats, and if it is correct to conduct an armed campaign. McGlinchey writes: “Fundamentally, radical republicans have united in their recognition of the ‘right’ to exercise armed struggle; however, they remain divided on when that right should be exercised and whether it should be exercised in present conditions and amid the absence of popular support”.

In comparison to the Troubles, the armed campaigns of republicans today are at a low level and have little support. Figures released by the PSNI show that there were 53 bombing incidents from 2015-16, and 30 from 2016-17. In the same years, there were 60 and 68 casualties of paramilitary-style assaults, 24 and 23 casualties of shootings.

Groups such as Continuity IRA and New IRA refer to the current ‘phase’ of their armed campaigns as ‘low ebb’. They are in the process of ‘rebuilding and reorganising’. Given their belief that it was the PIRA leadership that failed, rather than failed methods of individual terrorism, these groups or ones like them will attempt to continue their ‘armed struggle’ indefinitely, no matter what the circumstances or the divisive effect on the working class. The vast majority of the working class in the North oppose this and do not want a return to the dark days of the Troubles. Unless a powerful socialist alternative is built, however, the situation can eventually slip into renewed conflict.

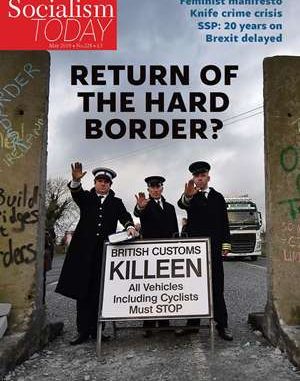

Brexit and the border

Some dissident republicans view Brexit as a much needed shot in the arm, putting the issue of the Irish border and sovereignty back into mainstream debate. A key part of the Good Friday Agreement’s ‘normalisation’ process saw the removal of the hard border, with army and police checkpoints. Davy Jordan, chairperson of Saoradh, said in November 2017 that “there is a generation of young people who don’t remember the physical manifestation. With a hard border you can see that the island is partitioned, so on that point of view we would very much see it as something to exploit”.

Dissident republicans will also take comfort from the collapse of the assembly in January 2017 as more evidence that Northern Ireland is a “failed political entity”. And the DUP-Conservative Party pact in Westminster also calls into question the Good Friday Agreement premise that the British government is ‘neutral’ in the context of the consent principle. Yet, while “united in their rejection of power-sharing at Stormont, radical republicans have failed to articulate a coherent strategy regarding the significant numbers of unionists within the North of Ireland who will not concede to Irish unity”, McGlinchey writes.

Indicating that even the hard-line Republican Sinn Féin cannot just ignore the feelings of Protestants, the party puts forward its Eire Nua ‘federalist’ policy. This envisages the four provinces of Ireland each having a level of autonomy, therefore providing “unionists in Ulster with a level of power at a local provincial level”. But McGlinchey points out: “Unionists appear presently unresponsive to the Éire Nua policy and also significantly reject any vote on Irish unity which would take place on a thirty-two county basis”.

Socialists oppose the coercion of either community. Catholics have the right not to accept living in the Northern capitalist statelet associated with discrimination, poverty and repression. Protestants have the right not to be forced into a united Ireland where they fear they would be a scapegoated minority for the ills of the bosses’ system.

Only a socialist programme, based on the unity of the working class in the North, Catholic and Protestant, linked to the working class in the South and workers’ struggles across Britain can provide a solution. A socialist Ireland would see the greatest possible democratic rights for all, without a hint of coercion. The socialist reorganisation of society on these islands would see a massive transformation of living standards, and a genuinely equal and voluntary federation of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, at last overcoming age-old national and sectarian divisions.

Unfinished Business: the politics of ‘dissident’ Irish republicanism

By Marisa McGlinchey

Published by Manchester University Press, 2019, £19.99

Be the first to comment