Bernie Sanders’ 2016 bid for the presidency shook up US politics. Attracting hundreds of thousands of people around a radical programme, it showed the potential for a working-class-based alternative to the two main parties. Tony Saunois reviews an account of the campaign, drawing the lessons for the 2020 presidential contest now under way.

Heather Gautney, an executive director of ‘Our Revolution’ and lecturer at Fordham University, New York, had worked for Bernie Sanders as a legislative fellow in his Washington DC office before the 2016 presidential campaign. She also served as a volunteer organiser during his bid for the presidency. Her book gives a valuable insight into the central political issues that confronted his campaign, his programme and objectives. As Gautney points out, she is an academic not a gossip columnist and this book is free of the personal tittle-tattle found in some accounts of major political battles. It is an illuminating account of this epic struggle, raising crucial issues of programme. However, the underlying weakness in her analysis lies in its lack of perspective and what Sanders and his supporters should do now.

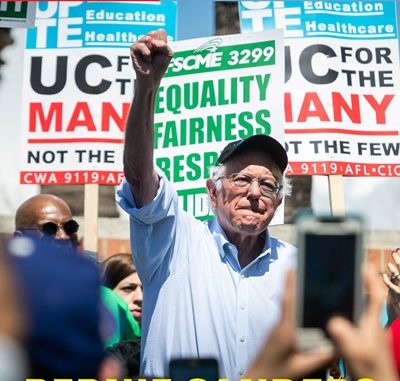

The mass movement that developed around Sanders in 2016 was one of the most important international political developments for the working class and socialists. It reflected the first stirrings of the awakening giant, the US working class, following on from the Occupy movement, the mass strikes in Wisconsin, and other upheavals. That millions were touched by the campaign was potentially a historic turn, reflecting their total alienation from the capitalist ruling class. They were looking for an alternative to the political caste or dynasties at the head of the Democratic and Republican parties.

This is a reflection of the social and economic crisis that has ripped through US society. It is a consequence of the declining position of US imperialism globally, even though it remains the most powerful capitalist power. In this it has some comparison with the social and political turmoil that shook British capitalism at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, which gave rise to revolutionary upheavals and the birth of the Labour Party.

The massive social inequality, seething anger and rise in poverty among swaths of the US population is illustrated throughout the book. Sanders managed to tap into it. Gautney relates the enthusiasm for Sanders’ demand for universal healthcare at a town hall meeting in McDowell County, West Virginia. There, 35% live in poverty, nearly half of them children. Less than 66% graduated high school, and the average life expectancy for men is 64 – in the world’s most powerful imperialist country.

She correctly explains the role of the Democrats in applying neoliberal policies in the 1980s and 1990s as the party swung further and further away from Keynesian policies. Gautney really exposes the hatred that existed, and remains, towards the Democratic elite represented by the Clintons and others. Hillary Clinton was known for her contempt of the working class and the poor. This was shown in her dismissal of Trump voters as “the deplorables”, and dubbing areas to avoid during the campaign as “fly-over states”.

Divisive separatism

From the outset, Gautney lays out four key themes with which to understand the movement around Sanders. In 2014 she wrote an essay in the New York Times discussing whether he should run, arguing correctly that “social class would be the major axis on which the new US politics would emerge”. She argued that, should Sanders throw his hat into the ring, he would take up the class issues. While “Hillary’s appeal to identity politics would rally corporate feminists it would do little to unite and empower America’s disenfranchised or move the dial on social inequality”.

In her account of the election campaign the pernicious role of identity politics is central, and how aspects of it are used by the ruling class to detract and blur issues of class by fostering ‘separatism’. Identity politics is a vital issue that revolutionary socialists need to confront, especially in the US where academia is in overdrive churning out supposedly new ideas based on it. These ideas have penetrated the workers’ organisations, and sections of the working class and youth. Of course, socialists must intervene energetically in all struggles defending the rights of women, opposing discrimination based on gender, race and sexual orientation, and champion the rights of all oppressed peoples.

The vicious attacks under Donald Trump on women’s and LGBTQ+ rights have made these particularly explosive issues. The recent decision in Alabama to ban almost all abortions is a measure of the vicious attacks under Trump. The Republicans hope it will provoke a legal challenge opening the door for a Supreme Court ruling that it should be applied across the country. This is likely to provoke mass protests which socialists and all workers need to support and intervene in.

Yet it is vital that these struggles are linked to and become an integral part of a united struggle of the working class against capitalism. The divisive trap of separatism, in all its forms, which will only split the working class, needs to be combated and energetically opposed. The experience of the Sanders campaign in dealing with this question is full of lessons. Socialists need to skilfully expose the threat posed by identity politics to the working class of all genders and races.

ID politics v working-class unity

Gautney concludes in her introduction that “class did end up as the fundamental organising principle of 2016”. This was reflected by Sanders and Trump – by the latter in a distorted or “hooligan” fashion, as she puts it. Gautney also admits: “What I did not see coming in June 2014, however, was how establishment Democrats would use gender and racial inequality to undermine progressive alternatives – and just how badly that strategy would backfire”. Later, in a lengthy chapter on identity politics, she gives clear examples of how it was used against Sanders by Clinton and Democrat leaders in the black community. They consciously tried to remove class from the debate.

Gautney gives example after example of how Sanders was attacked by some individual leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement and others. He was accused of being “tone deaf” to the plight of people of colour despite his attacks on Wall Street. Black Democratic Party congressmen were wheeled out to endorse Clinton by playing the identity politics card. James Clyburn from South Carolina endorsed Clinton. He and Cedric Richmond from Louisiana claimed that Sanders’ plan for free public higher education would undercut historically black colleges and universities.

Gautney strongly attacks what she argues was the “establishment Democrat practice of branding its conservative class politics as racial justice”. She criticises those claiming to speak on behalf of the ‘black community’ as a whole, describing this as an “abstract term” because it obscures the “class and power inequalities among black Americans; since victories in the 1960s and 1970s, inequality has advanced to such a degree that it is today much higher than amongst white Americans”. She warns: “In capitalist society, all politics is class politics. Assuming that an essential unity of ‘community’ exists within particular racial, ethnic and gender categories risks obscuring class hierarchies and relations of exploitation among people within such groupings”.

None of this means, of course, that we should not recognise the brutal racial and gender oppression in capitalism, particularly in US society. On the contrary, it is essential to fight it. It is also necessary, however, to link it to a united class struggle against capitalism and to draw out the class distinctions that exist within racial, gender and/or other groups. Gautney cites the literary theorist, Walter Benn Michaels, who said in an interview: “You know you live in a world that loves neoliberalism when having some people of colour who are rich is supposed to count as good news for all the people of colour who are poor”!

Gautney argues that the same could be said for “versions of feminism that exploit women’s sense of purported biological unity and common experiences of patriarchy in order to paint an elite woman’s success as a universal win – instead of fighting for material equality with men and among women”. We might add among men as well. Yet to achieve this it is necessary to break with capitalism and link all such struggles with the need for a socialist transformation of society.

The ‘European socialism project’

Heather Gautney also deals with aspects of Sanders’ programme, but this is the weakest part of her analysis. The fact that Sanders was identified as a socialist, raising radical demands that reflected class issues and appealed to big sections of the working class, was positive, particularly in the context of US society. Socialism has been put on the agenda for the first time in generations. However, this positive development is at an early stage and has limitations which need to be overcome.

In her introduction, Gautney deals with the question of Sanders’ ‘socialism’ and what is meant by it. Sanders had asked her to prepare a paper on “universal healthcare, tuition-free college, public pensions and other aspects of European democratic socialism”. She explains: “The European socialism project that he proposed to me… involved preparing backgrounds on social welfare systems in Europe, and Denmark in particular”. In other words, for them, socialism is the welfare state that exists in most northern European countries. Given the absence of such a system in the US, understandably, this proposal is tremendously popular and appears very radical.

Moreover, the US, like all capitalist countries, has been dominated by the neoliberal agenda for decades. The leadership of the Democratic Party has been a driving force in implementing it since the late 1970s. Bill and Hillary Clinton have been in the forefront of this drive. The reforms demanded by Sanders on health, education, infrastructure investment and breaking up the banking system seemed particularly radical when compared to the policies defended by the established leadership of the Democratic Party.

However, the reforms Sanders campaigned on did not constitute a break from capitalism. Gautney is quite explicit about this when dealing with Sanders’ call for a ‘political revolution’: “His campaign was not calling for a radical social and political restructuring of power in the United Sates, like modern revolutionary movements have done in Cuba or Bolivia and elsewhere. Bernie did not associate himself with anti-capitalist politics or seek to nationalise major industries (though he has in the past). Rather, he advocated for increasing government regulation and corporate taxation and removing elements of the social system, like healthcare and higher education, from the market economy. He also promoted policies to revive public investment and social safety nets… much like the industrial Keynesianism of the post-war era”.

Sanders carried the US socialist leader Eugene V Debs’ key chain in his pocket. Debs was a founder member of the International Workers of the World and a leader of the Socialist Party of America which at its peak had more than 100,000 members and over 1,000 members elected to public office, including two in Congress. Debs ran five times for the presidency winning nearly a million votes in 1920. Sanders’ policies amounted to a ‘reformed’ capitalism rather than a socialist break from it – and are a pale reflection of the programme of Debs!

In addition, Sanders’ relatively radical demand for a ‘welfare state’ comes at a time when the ruling classes in Europe are in the process of dismantling it. This flows from today’s era of capitalist crisis, in contrast to the period of post-war economic upswing when these reforms could be conceded by capitalism in Europe.

Up against capitalist class interests

Nonetheless, Sanders’ reforms were far too much for the US ruling class and the leadership of the Democratic Party to accept. The Democrats had swung further to the right and embraced neoliberalism. Faced with revolutionary convulsions and a mass movement, the capitalist class may be compelled to introduce some reforms temporarily. However, the introduction of sustained reforms is something that the system cannot afford at this time of crisis.

When Sanders launched his 2020 bid for the nomination in Iowa, he made a blistering attack on the horrors of US capitalism. He exposed the pharmaceutical industry, banks and big corporations, and the tax avoidance of Google, Amazon and other companies. Healthcare for all, a $15 minimum wage and other demands were promised should he win the presidency. He correctly argued for massive investment in infrastructure. He also warned that the major corporations would use their immense power to oppose these policies, and he threatened to stand up to them. But the question is how?

Unfortunately, Sanders made no reference to taking these massive corporations into public ownership under democratic control. His programme was left at the utopian aspiration of trying to regulate capitalism in the interests of all rather than breaking from it and introducing a democratic socialist alternative. This echoes what existed in Europe soon after the second world war. In recent decades, however, the capitalist class has abandoned such policies in favour of neoliberalism and its programme of deregulation and privatisation. Even with greater state intervention, the current era of capitalist crisis and the prospect of deepening recession would lead to further attacks on the working class. Any temporary reforms conceded would be taken back again. A return to post-war upswing and long-lasting reforms is wishful thinking today.

The CWI recognised the tremendous significance of the movement that developed around Sanders and the radical reforms he advocated. It is essential to engage with the millions drawn behind it and to fight for those policies. However, it is also necessary to explain the limitations in that programme and warn of the consequences if it is not accompanied with a struggle to build a mass movement and a new party of working people capable of fighting for a socialist programme. Failure to do so – and, instead, wait until a mass movement has been built before raising the need for a socialist programme – will not assist workers and young people to prepare for the enormity of the tasks ahead in the struggle to defeat the most powerful capitalist class on the planet.

Trying to save the Democratic Party

It was necessary to explain this in the 2016 campaign and it is still necessary, as a part of the struggle to defeat Donald Trump. Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, a caucus within the Democratic Party, elected to Congress from New York – have recently demanded that a 15% interest rate limit is placed on all domestic loans including credit cards. This is a crucial issue given the high levels of domestic debt and will be extremely popular. However, it is necessary to go much further. Although 15% interest rates will still allow such institutions to make a killing, the US financial institutions will fight this proposal tooth and nail, while seeking ways to evade such restrictions. It is necessary, therefore, to link this call with the demand for the nationalisation of the banks and financial institutions under democratic control, rather than simply the break-up of the banks into smaller companies with a ceiling on interest rates.

Sanders is currently ahead in the polls for the Democratic primaries running up to the 2020 presidential campaign. But the entry into the race of more candidates – like Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden with a base in the trade union apparatus – may mean that the battleground is more complicated than in 2016. This raises the important question, touched on in Gautney’s book, around Sanders’ decision to run as a Democrat in 2016, rather than taking the bold steps necessary to form a new party and break from the Democrats. That is posed today as Sanders again attempts to win the Democratic Party nomination. Gautney defends his mistaken position.

At his launch in 2019, Sanders made it clear that he was running for the nomination to channel the newly radicalised young people and workers into the Democrats: “So if – if the Democratic Party is gonna do well in the future – I think they have to reach out to those independents, including by the way a lot of young people, a lotta people of colour, and bring them into the Democratic Party. And I think I am in a good position to do that”.

Sanders is attempting to repeat in the Democrats what exists in the British Labour Party: two parties in one. This untenable situation has seen a fifth column of right-wing, pro-capitalists free to derail and sabotage the Corbynistas. In reality, there was an element of two parties in one at the Democratic convention in 2016, and it ended with Sanders ‘reluctantly’ endorsing Clinton! Unfortunately, Sanders sees his role as saving the Democratic Party by taking a radicalised layer into it. His 2020 bid for the nomination is starting from the same mistaken premise on which he ended his bid in 2016. The Democratic Party is a thoroughly capitalist party. A clear break from it and the establishment of a new party of the working class is necessary.

In some other countries, historically, the process of forming mass workers’ parties included individuals or groups breaking from capitalist parties. In 19th century Britain, this involved trade unionists and individuals who were linked to the Liberal Party but were also involved in the embryonic steps to form the Labour Party. In Greece in the 1970s, the origins of what became the mass socialist party, PASOK, are traced to George Papandreou who broke from the liberal capitalist Centre Union.

This type of development may be repeated in the process of building a new working-class party in the US – and would be possible around Bernie Sanders, although he has actively opposed taking such a step so far. Other initiatives are also possible, with new parties or groupings emerging from workers, trade unionists and others oppressed by capitalism, initially at state level. What is clear, however, is that the social conditions and support exist – reflected in the battles already taking place – for the formation of a mass workers’ party.

Rigged Democratic convention

Heather Gautney graphically shows that the primary system was fixed against the ‘outsider’ Sanders and his supporters who “crashed the party”. The battle at the convention and her vivid description of events there make this crystal clear. The radical delegates were treated as gate-crashers by the established party machine. Many of them were looking for a much more radical stance by Sanders.

Gautney describes how at the convention votes went to Clinton from states where Sanders had won a clear majority in the primaries. Sanders won Michigan yet the convention votes were 46 to Clinton, 44 to Sanders. He had won the New Hampshire primary by 60% to 38%, but the convention tally announced 16 each! The party elite had played the super-delegate card, a double-lock mechanism on top of the rigged primary system to stop an ‘outsider’. This system has only been partially reformed, following an outcry at the cynical way it had been wielded.

At the convention, many Sanders supporters were enraged, booing the party leadership and the ideas it represented. Gautney cites Sanders giving instructions to his supporters not to “disrupt the convention” and to remain calm. He even launched a follow up ‘unity tour’ with the newly elected and establishment backed Democratic National Committee chair, Tom Perez. He was one of those who suggested to Clinton that she use identity politics to “defame Bernie”!

Gautney justifies Sanders’ endorsement of Clinton as the way to block Trump. However, refusing to stand independently drove millions into his arms as they were repelled by Clinton. Trump was able to present himself to sections of US workers as ‘anti-establishment’, and a defender of the working class. Clinton’s dismissal of these voters facilitated that narrative. This affected not only white Americans from the rust-belt states. As Gautney points out, 29% of Latinos also voted for Trump! The lesser evil argument does not hold water, as millions who opted for Donald Trump could have been won to Bernie Sanders but were repelled by Hillary Clinton.

Building a real political alternative

Sanders could have used the platform he had won to break from the Democrats and launch a new party for US workers. His failure to do so in 2016 was a missed opportunity. Even if he had not secured victory then he could have amassed the forces to lay the basis for a real challenge to Trump from the left in 2020. By adopting the stance he has today he is wrongly herding his supporters into the dead end of the Democratic Party, at a time when the basis exists to launch a new party for the workers and young people who are desperately looking for an alternative.

The idea that it is possible to transform the Democratic Party may appear more appealing at this stage, given the electoral victory of some around the Democratic Socialists of America like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. While the party establishment may have tolerated a few individuals being elected, however, they would never allow the party to be transformed from top to bottom. This would necessitate the driving out of those who are wedded to US capitalism, Wall Street and the big corporations.

Rather than directing his supporters into the Democratic Party, Sanders should be taking the steps to build a mass alternative to the Democrats and Republicans. A convention of his supporters could reach out to the organised working class in the trade unions, workplaces and community organisations, and appeal to all those who wish to fight for an alternative to Trump, the Democratic corporate elite and capitalism. Such a convention could lay the base for a new party, rooted among the working class of all races, genders and sexual orientation who are actively participating in the struggles taking place. It would need to set up a party that is democratically controlled, with accountable leadership, and acting as representatives of all working people.

This is the way forward and the objective conditions to build such an alternative exist now. The year 2016 represented a political and social earthquake in US society. Millions rallied behind the Sanders campaign, yet the opportunity was lost to establish a real political alternative for the working class. Unfortunately, it seems that Sanders is preparing to repeat his earlier mistake. Nonetheless, from these struggles and experiences, a broader layer of workers and youth can begin to see the need to build a new party with socialist policies. The CWI will continue to assist workers in the US in drawing these conclusions.

Crashing the Party: from the Bernie Sanders campaign to a progressive movement

By Heather Gautney

Published by Verso, 2018, £9.99

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

Be the first to comment