Days before the 30th anniversary of the massacre, on 3-4 June 1989, of hundreds, possibly thousands, of unarmed demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, China’s Defence minister, General Wei Fenghe maintained that the crackdown was absolutely justified!

“That incident”, he said in Singapore on 2nd June, “Was a political turbulence and the central government took measures to stop the turbulence which is a correct policy.”

The events of May-June 1989 in China constitute a dramatic and horrific illustration of the lengths to which a ruling clique will go to maintain its rule and privileges. It was forty years since Mao Tse Tung at the head of the People’s Army had presided over the wiping out of capitalism and landlordism from that vast country in what Marxists describe as the second greatest event in world history after the Russian Revolution. A mass movement was developing from below and beginning to take the form of a political revolution against the Maoist dictatorship.

From the beginning, China had been a deformed workers’ state, with no elements of workers’ control or workers’ democracy which provide the vital oxygen for developing the elements of a democratic workers’ state. Without it, as in the Soviet Union after the rise of Stalin, the ruling clique would zig-zag from one way of running the economy to another – centralisation, decentralisation and back. This included the ‘Great Leap Forward’ begun in 1958 and the infamous ‘cultural revolution’ of Mao in 1966 in which hundreds of thousands of talented youth and workers perished.

By the Spring of 1989 – thirteen years after Mao’s death, students, some inspired by the ‘reformer’ Hu Yaobang, began to challenge the ruling elite under Deng Xiaoping. Their demands were simple and modest such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech, free elections, freedom of organisation etc. but they challenged the control and privileges of the so-called Communist Party that ran the ‘People’s Republic’ of China.

Aims

There were, and still are, varying opinions as to whether the aims of the protests were to move towards market capitalism and the so-called democracy of the US and other major powers or to try and take control of the economy and the state into the hands of democratically elected representatives of the working people – a political revolution. Before the end of 1989, that very same question was posed across the whole of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

As in all revolutionary movements, in China in April and May of that historic year, there was a profusion of ideas and theories as to what was needed. What was lacking was any party, even in embryo, with leaders who had a clear idea of how workers and young people could channel that revolutionary energy into an overthrow of the old regime.

As in Hungary 1956 or elsewhere, a revolution can begin without a revolutionary party, and go nine-tenths of the way towards victory. Workers and young people were prepared to fight to the end – to the extent of sacrificing their lives. In these conditions a revolutionary party can be rapidly built. But without it, and without elected fighting bodies like the soviets, the most favourable situations can turn into their opposite and a whole period of reaction can ensue.

Whatever the aims of the participants were in 1989, it is clear that the eruption of a mass movement in the capital city and in towns and cities across China was threatening the dictatorial rule of the Party bureaucrats in Beijing. A sure sign of the revolutionary nature of the upheaval was the participation of school students as well as students at university. The wind of revolution was blowing the tops of the trees.

The Guardian says millions “including police, judges and naval officers” were drawn in, “prompted by anger at corruption and inflation, but also the hunger for reform and liberty” (1 June 2019). Once workers began to lend support to the student protests and take action, and the forces of the state began to refuse orders – the murderous suppression of the uprising began.

Strikes

Both before and after the massacre in Tiananmen Square, there were mass protests in hundreds of cities across the country. According to leaked government documents collected together in the ‘Tananmen Papers’, protests were reported in 341 Chinese cities between April and June 1989.

Wikipedia writes, “After order was restored in Beijing on 4 June, protests of varying scales continued in some 80 other Chinese cities….In Shanghai, students marched on the streets on 5 June and erected roadblocks on major thoroughfares. Factory workers went on a general strike and took to the streets as well; railway traffic was also blocked. Public transport was also suspended and prevented people from getting to work.” The protests in Shanghai continued for more than a week.

The authorities carried out mass arrests. They saw the threat from workers taking action as more of a threat to their future than students; “many” were reported to have been summarily tried and executed. Students and university staff involved were permanently politically stigmatised and many were never to be employed again.

Many Asian countries remained silent throughout the protests. The government of India did not want to jeopardize a thawing in relations with China. The governments of Cuba, Czechoslovakia and East Germany, fearing similar uprisings at home, denounced the protests. Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East and Asia.

After these events, the bureaucracy moved in a more pro-capitalist restoration direction. This led to a hybrid, state capitalism. It is this regime which has moved again to clamp-down on all protest and exert mass repression.

Today

The Chinese economy today is more than thirty times larger than it was in 1989. The Economist points out that in the late ‘80s, in nominal terms Soviet-American trade was $2bn a year. Now, trade between America and China is €2billion a day! In June 1989, the US President, George H W Bush wrote to Deng Xiaoping urging joint efforts to ensure the “tragic recent events” would not harm relations.

Today, more cars are sold by General Motors in China than in the US. China vies with the US in terms of economic and military superiority but the Economist points to the dilemma of trade relations not being quarantined from “hard questions about whether countries are partners, rivals or foes”. Philip Stevens in the Financial Times commented on 17 May that China is seen in the US “not just as a dangerous economic competitor but a looming existential threat. Beijing may not have the same ideological ambitions as the Soviet Union, but it does threaten US primacy.”

Ma Jian, the author of a book called ‘Beijing Coma’ and an activist in in 1989 writes that, “Within months of the Tiananmen massacre, world leaders were rushing back to Beijing to deals, claiming that collaboration would help bring about change”, but “As the terror of Tiananmen is being re-enacted in the gulags of Tibet and Xinjiang, western leaders shake hands with President Xi and look the other way.” (Guardian Review 1 June ’19).

An editorial in the same paper speaks of a “silence which began at home” spreading internationally over the estimated one million Uighurs and other Muslims incarcerated in detention camps in Xinjiang and forced to undergo political indoctrination.” It comments that “The build-up of the mammoth domestic security apparatus makes a mass movement in the manner of 1989 impossible”. But even this journal of the bourgeoisie adds: “The unexpected and implausible does happen”!

Living standards in China have undoubtedly improved and huge modern industries have developed rapidly. But the regime under Xi Jinping is, if anything, more monolithic than previous ones.

Capitalism

Inside China there has been no straight line development towards the establishment of fully capitalist relations. The collapse of Stalinism and the capitalist ‘Shock Therapy’ treatment that plunged the economies of the former Soviet Union into crisis in the early ’90s stayed the hands of the Chinese bureaucracy. So too, probably, news of the fate of the ‘Communist’ generals who tried to recover their power in August 1991 (and lasted less than three days!).

Still today there is a very large element of state ownership and state control in the now massive Chinese economy. The proportions zig-zag. The capitalist press outside of the country still uses the same phrase as the CWI to describe the Chinese economy – a ‘special from of state capitalism’! The Financial Times quotes analysts who argue that the ‘Communist’ party “controls levers Trump can only dream of”. The Economist in May bemoans the fact that any US-China trade deal will do little “to shift China’s model away from state capitalism. Its vast subsidies for producers will survive.”

Xi Jinpeng is a dictator and part of a very rich elite. But he still uses Marxist and Maoist phraseology as a cover for autocracy, while viciously repressing opposition and all civil and trade union rights.

At a time when the world’s economic and political relations are in turmoil, and austerity and super-exploitation reach new depths, explosions of anger from below can break out in almost any country and take on unexpected dimensions. The Chinese regime knows only too well that lessons drawn from the past can lead on to more successful challenges to their power in the future. This is what lies behind their pervasive censorship of all media and a total ban on any mention of the third of June date.

The CWI has to strive to reach ever wider layers of workers and young people in China and throughout Asia in order to build the forces necessary to win real and lasting victories on the way to establishing a socialist world.

Tiananmen Square 1989: Counter-revolution crushes China’s democracy movement – Workers and students put up heroic resistance

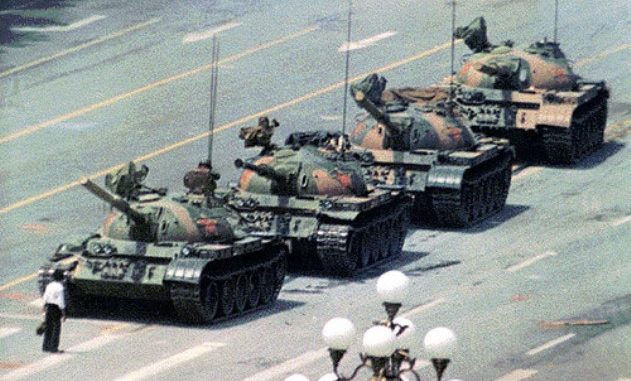

ON 3-4 June 1989, Deng Xiaoping and other aged leaders of China’s so-called ‘communist’ party, ordered 200,000 troops to crush a two-month long movement of workers and students against bureaucratic rule and for workers’ democracy. At least 1,000 people were killed in central Beijing and 40,000 arrested in the following weeks.

Below, we reprint an extract from Militant editorial (the forerunner of The Socialist) written at the time:

Thousands have been arrested and thrown into jail. Thousands more have gone into hiding. Students’ and workers’ leaders have been rounded up, including the founders of the autonomous trade union organisation.

Telephone hotlines have been set up for informers. Every day prisoners are paraded on the television, chained and obviously beaten, to create an atmosphere of fear and despair.

In true bureaucratic style, Deng Xiaoping, Li Peng, and their henchmen are denouncing their opponents as ‘counter-revolutionaries’. Strange counter-revolutionaries who sung the Internationale as the tanks tore into them on Tiananmen Square!

The hardliners are reviving the Stalinist language of the so-called Cultural Revolution, during which Deng himself was denounced as a counter-revolutionary and purged by the Maoist faction.

According to the old guard, the movement against them was a plot led by “a very small number of political hooligans and evil-doers”.

As in the Cultural Revolution, the leaders also point to the ‘black hand’ of American imperialism, and are attempting to whip up xenophobia, hatred of foreigners, to bolster up their regime. Yet day after day, the ‘small group of hooligans’ numbered hundreds of thousands on Tiananmen Square.

Such a mighty wave of opposition can arise only from deep social roots.

It was triggered off by the bold action of the students. But the movement, which drew in wide sections of the workers and other strata, was stimulated by accelerating inflation and unemployment, growing inequality between a prosperous elite and the majority of workers and peasants and rampant corruption among managers and party bosses.

The protest expressed a profound hatred of the bureaucracy. The bloody repression of 4 June evoked no celebrations from a populace saved from ‘counter-revolution’. On the contrary, the massacre provoked mass protest and clashes throughout China.

For a whole week, 15 major cities were convulsed by mass demonstrations, a blockade of roads and railways, extensive strikes and clashes with the police and army, with the virtual paralysis of the main industrial centres.

Step by step the regime has clamped down. Yet in Shanghai, the country’s biggest industrial centre where there has been an extraordinary movement of the students and workers, the mayor has so far been very cautious in carrying out repression, though he does not rule out more drastic measures as the movement ebbs.

The hardliners are now firmly back in the saddle. They are trampling on the mass movement with steel studded boots. This is their revenge against a movement which shook the bureaucracy to its rotten core.

From the start, the bureaucracy was split. The commanders of the 38th Army based in Beijing refused to move against the students and workers. For two weeks, behind closed doors, Deng, Li and the old guard fought a bitter struggle for control of the key levers of the state apparatus and the army. They were suspended in mid-air, powerless to enforce their rule.

The students’ call for democracy and an end to bureaucracy and corruption drew out hundreds of thousands of workers onto the streets. Even sections of the bureaucracy and members of the [‘communist’] party were affected. When the army first moved against them, the human barricades fraternised with the soldiers and the army cracked, with many soldiers throwing off their uniforms and some handing over their weapons.

Had the students and workers organised committees of workers, soldiers and students and peasants… for the overthrow of the bureaucracy and the introduction of workers’ democracy, the army could have been split from top to bottom.

Decisive sections could have been won over to the workers. All the conditions were there, apart from a clear Marxist programme, for the overthrow of the bureaucracy. But as in all revolutionary situations, the movement reached the point of either/or – either the overthrow of the bureaucracy, with power being taken into the hands of the workers, or a bloody counter-revolution, with the bureaucracy re-establishing its rule by naked repression. Without the decisive winning over of the troops, most of the military commanders, faced with a challenge to the rule of the bureaucracy, fell in line with the hardliners. …

The hardliners are now tightening their grip on the regime and over society. The head of the security apparatus, Qiao Shi, appears to be a key figure in the new leadership.

Deng, once hailed as the great reformer, has abandoned reforms and his reformist allies like Zhao Ziyang who has disappeared. Zhao and the reformist wing of the bureaucracy may well have favoured further economic liberalisation and a relaxation of political control within the party and the state. But their position was fatally undermined by the economic chaos which resulted from their reform policies.

More repression

Significantly, Deng’s first appearance on television was with the generals, “the iron great wall of the state”, gratefully thanking them for their success in suppressing the ‘counter-revolution’.

But by the same token, the generals have been brought nearer to the centre of power. The military bureaucrats will want their say in running the state. The factions within the military will be embroiled in new struggles within the leadership which will inevitably break out again in the future. … Their only policy now is repression, repression and more repression.

But the economy is in crisis, in spite of the rapid growth of the recent period. The reforms, which opened the door to foreign firms and let loose an element of private enterprise in the countryside, have produced inflation of over 35%, shortages of basic food products and mass unemployment…

Although Deng is still saying the reform policy will continue, in reality there will be a period of re-centralisation. There will be re-centralisation and curbs on private enterprise, in a desperate effort to control inflation and bring down unemployment.

But this in turn will produce new problems. Under modern conditions the industrial sector cannot develop in isolation, without the import of technology and specialised products from the world market. Curbs on foreign investment, moreover, would undermine the development that has taken place recently, especially in the industrial centres on the East coast…

But the inevitable contradictions will sooner or later produce another zig-zag, when the bureaucracy, with new leaders coming to the fore, will lurch back in the other direction…

Eyewitness in China The events in Tiananmen Square May-June 1989,

by Steve Jolly. £1.50 (sterling)

Available from Socialist Books, PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD. 020 8988 8787, www.socialistbooks.org.uk

Eyewitness to massacre

ON THE eve of the 3-4 June 1989 bloody massacre in Tiananmen Square, Steve Jolly, a witness and participant in the April-June events in China (who was then visiting from Australia), was invited to address the formation of the Beijing autonomous trade union.

Because of the previous arrests of a number of worker activists, the meeting was switched to Tiananmen Square and Steve ended up speaking to a meeting of 500,000 people!

“I expressed solidarity from workers and students in Britain… to the movement in China and how they had captured the imagination of the workers and students and peasants internationally.

“I said: ‘You are being called counter-revolutionary and pro-capitalist. But any government that calls itself communist, arrests union leaders and stands against democratic rights is not a real communist government – you are the real communists, you are the ones who hold the banner of revolution, not this government.'”

Later Steve recounts the moments when Deng Xiaoping’s regime launched its counter-revolution.

“During the course of the day [3 June] 3,000 troops moved to one of the buildings next to Tiananmen Square…

“Workers and students were so confident that they could persuade the 27th army not to move against them. But at midnight it all started. They came first with tear gas followed by troops with electric batons. After that it was troops on foot, then tanks and army personnel carriers.

“Students lit up the barricades all over the city and they had street battles. But because they hadn’t armed themselves and had refused on previous occasions to take arms from soldiers who had offered them, they suffered the consequences.” (from Militant 16/6/89)

‘Eyewitness in China, The events in Tiananmen Square May-June 1989’, by Steve Jolly, is incorporated into ‘Tiananmen 1989 – Seven Weeks that Shook the World’ compiled by chinaworker.info

Be the first to comment