“The only certain outcome of the general election”, argued the Socialism Today editorial published two weeks before the last contest (issue No.209, June 2017), “is that none of the contradictions besetting the political and social relations that sustain British capitalism” would be any nearer to resolution at the end of it.

“The crisis of capitalist political representation signalled by continuing Tory divisions”, we wrote then, “the uncertainties surrounding the Brexit negotiations; the battle around a new Scottish independence referendum… almost all the conceivable electoral scenarios will bring them into sharper relief”.

Two-and-a-half years later, the underlying contradictions have only intensified and the political consequences are, if anything, even more unpredictable.

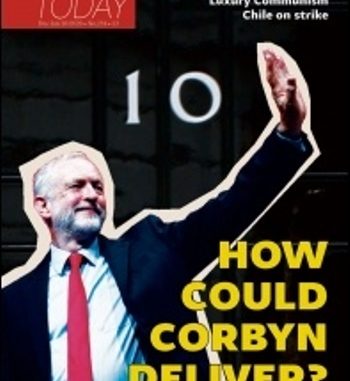

But, while there are a range of possible outcomes from the 12 December election, the most immediately important for the workers’ movement is the prospect of a Jeremy Corbyn-led government, with either a Labour parliamentary majority or in another ‘hung parliament’, and the consequent question: how could a prime minister Corbyn deliver the reforms he has promised the working class?

The capitalists’ fear of Corbyn

No section of the ruling class is discounting the possibility of a Corbyn-led government this time around. The clearest evidence for this is the promises on public spending announced by the Johnson-led Tory Party.

The pledges made by chancellor Sajid Javid would take public capital spending, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), back to the levels of 1979 – as Margaret Thatcher was about to become prime minister.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the day-to-day levels of government spending promised are similar to those implied by Labour’s manifesto at the last election – Boris Johnson as a circa 2017 Corbynista! What happened to the mantra that there was no alternative to austerity?

In its own way, this is a confirmation of the role that the mere existence of a workers’ party could play in changing the balance of class forces and acting as a check on the capitalists.

Even if at this stage, it is expressed through Corbyn’s leadership, which is still only a potential bridgehead for re-establishing working-class political representation through the Labour Party, rather than a completed transformation of Labour from Tony Blair’s capitalist New Labour into a mass party of the working class.

Contrast the situation now with the run-up to the 2015 election, when Ed Miliband’s shadow chancellor Ed Balls responded to a Tory dossier on Labour’s allegedly excessive, ‘unfunded’ spending commitments of £21 billion – just £21 billion! – by flatly denying he would overturn the 1% public-sector pay limit or reverse council funding cuts.

Javid is promising a spending increase of £13.4 billion for 2020-21 and £20 billion a year on capital projects – which John McDonnell counters with a £150 billion ‘social transformation fund’ over five years and an extra £55 billion a year ‘green industrial revolution’ capital spend.

Keynesianism, public spending to keep capitalism going – with the bulk of it financed by borrowing rather than increased taxation – is back on the agenda.

But if the capitalists have been compelled to accept that their political representatives can no longer pursue an unmitigated pare-back-the-state austerity agenda, why do they fear Corbyn and McDonnell’s Keynesianism more than that of Sajid Javid?

It is not primarily a matter of the scale of the spending commitments (although at a certain point quantity can turn into quality).

Javid’s calculation – totally exaggerated, naturally – is that McDonnell’s programme would increase borrowing by £1.2 trillion.

But, even if that was so, it is actually about the same amount as the national debt has increased since the 2007-08 financial crisis – including the nine years of Tory or Con-Dem coalition government – from £530 billion in September 2007 to £1.79 trillion today (83.1% of GDP).

Clearly, it did not provoke “the economic crisis within months” that Javid warns would happen under Corbyn.

The capitalists’ real fear is that workers’ expectations would be aroused, and their confidence raised by a Corbyn-led government which, in turn, could be pushed to go further than it initially intended to go in encroaching upon the capitalists’ profits – and control.

Javid’s £1.2 trillion figure, for example, includes an ‘expert estimate’ by the Confederation of British Industry of the cost of nationalising railways, water companies, Royal Mail and the energy network, by paying for the shares at market rates, £322 billion.

Companies are already issuing bonds with ‘nationalisation event’ clauses guaranteeing instant repayment at face value.

But it is not hard to see that, if a Corbyn-led government was embroiled in legal battles to carry out its plans, the demand raised now by the Socialist Party, for nationalisation with compensation only on the basis of proven need democratically decided, could rapidly gather mass support.

Similarly, if John McDonnell’s green industrial transformation investment plans faced a capital strike.

The Keynesian economic columnist Larry Elliot – a rare non-Blairite in the pages of the Guardian newspaper – describes McDonnell’s strategy as the state taking “the initiative in the hope that through public investment it will encourage private investment” (30 September 2019).

But if the capitalists prove reluctant to invest their hoarded profits for the returns on offer – companies’ cash balances, about £750 billion, are at a record 35% of GDP – then the arguments would grow for wider nationalisation, of the major companies themselves.

As Hannah Sell explains in her review of Aaron Bastani’s book, Fully Automated Luxury Communism [in the December 2019 Socialism Today], there is no substitute for a clear programme of democratic public ownership of the banks, financial institutions and major companies under workers’ control and management, as the basis to overcome the imperatives of the capitalist market system.

The capitalists look on with trepidation at the possibility of a Corbyn-led government – and are urgently debating what to do to try and manage the situation.

Brexit, and Tory dysfunctionality

If a Corbyn-led Labour Party cannot be firmly relied upon to act as previous right-wing Labour governments did as a shield for the capitalists’ interests – while New Labour was an unambiguously reliable capitalist party – the Tory party under Johnson is also no longer an optimal tool for the political representation of the capitalists.

Johnson has moved ruthlessly to consolidate his grip on the Conservative Party since just 92,153 people – overwhelmingly in the upper wealth brackets, white, elderly, mainly living in southern England, and accounting for less than one-fifth of one per cent of the 46 million UK electorate – voted him to victory in the Tories’ summer leadership contest.

Philip Hammond, four months ago the chancellor but now unceremoniously denied the Tory whip to be bundled out of parliament, has spoken of the “real narrative” of “the Vote Leave activists – the cohort that has seized control in Downing Street and to some extent in the headquarters of the Conservative Party – [who] want this general election to change the shape of the Conservative Party” (29 October).

At least 16 remainer Tory MPs who quit or lost the whip – including Oliver Letwin, David Gauke, Dominic Grieve and Johnson’s brother Jo – have been replaced by leave supporters, leaving ex-leader and stalwart of the European Research Group of right-wing Tory MPs, Iain Duncan Smith, to gloat that the Tories “are the Brexit Party now”.

Hammond has also argued that Johnson is especially tied to those in the more speculative, offshore-linked wing of the UK’s financial sector who support leaving the European Union even in a no-deal Brexit, in contrast to the bulk of British big business who want to retain, at least, a close alignment with the EU bosses’ club.

This fault line is completely unresolved by Johnson’s proposed ‘get Brexit done’ withdrawal agreement treaty with the remaining EU27 member states.

At the time of writing, the Tories have yet to agree their manifesto, with arguments raging even at cabinet level on whether they should rule out any extension to the transition period – effectively continued EU membership without votes at EU meetings – that would come into effect after the withdrawal treaty is approved.

The transition period, during which Johnson aims to negotiate a free-trade deal with the EU, will finish in December 2020. Then Britain and the EU would move to ‘no-deal’ World Trade Organisation terms if there was no trade pact – unless an extension is requested, according to the withdrawal agreement timetable, by July next year.

Any trade deal would have to be approved by all the national and regional assemblies of the EU member states.

This includes, for example, Belgium’s self-governing parliament of Wallonia, which nearly derailed the seven years of negotiations between Canada and the EU that produced the 2016 Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), leading the Canadian trade minister to walk out of one meeting in tears.

In times of economic upswing it is possible to achieve unity, if not honour, amongst the capitalist thieves. But smoothing over the problems caused when one or another section of the capitalist class in a particular country has not had its interests met in treaty negotiations is more difficult in an era of capitalist stagnation, at best, with another cyclical downturn looming. The one thing the Brexit saga will not be on 13 December is ‘done’.

The Tory party has not yet definitively divided into the modern-day equivalents of the 19th century rival Conservative groupings, the Peelites and the Disraeli-Derby Conservatives, that emerged during the ructions over the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. If the Tories win the same seats as they did in 2017 there will still be 134 remainer MPs on their benches.

Nonetheless, such a split is on its way. Faced on the one hand with the possibility of a government led by Jeremy Corbyn – who is additionally also an unreliable defender of capitalist interests on the EU and Brexit – and a dysfunctional Tory party on the other, the crisis of capitalist political representation is ever more acute.

The Blairites: they haven’t gone away

Enter, once again, Tony Blair. Writing in the Financial Times after the election was called, Blair denounced Jeremy Corbyn’s “campaign launch speech attacking ‘dodgy landlords’, ‘billionaires’ and a ‘corrupt’ system”, as “textbook populism. It is no more acceptable in the mouth of someone who calls themselves left wing than in the mouth of Donald Trump’s right”, he said (4 November).

Arguing that “the spine of British politics has always been a solid centre” – read, balancing the interests of the capitalist system, as a whole – which had now “fractured”, Blair warned that repairing and healing it “will take time”.

The immediate issue is “how, in this election, do we preserve that possibility”. In a barely-coded battle plan for future political realignment – urging “sophistication and care” for now, no premature moves – he argued that “we need to get into parliament many reasonable and capable politicians of all parties who will not spout populism”.

This includes, he wrote, “a core of good Labour MPs who will not be whipped into supporting policy they do not believe in”, but also anti-Johnson Tories: “Parliament would be worse without the Conservative independents”.

“After this election”, Blair concluded, is the time when “the real battle over the future of British politics will begin”.

The Blairite former foreign secretary David Miliband has also re-joined the fray, arguing that “an early 20th-century class-based structure is struggling to cope”, and calling for a ‘democratic reboot’, including electoral reform and a written constitution.

The Blairites, it is true, were hit by Tom Watson’s unexpected eve-of-poll resignation as an MP and deputy leader.

Watson, who established the Future Britain Group to organise the ‘social democratic tradition’ within the parliamentary Labour Party’ after the defection of eight MPs to the Independent Group, earlier this year, was criticised with some bitterness by anti-Corbyn MPs for his “self-centred” decision, faced as he was with growing attacks for his role in a Westminster sexual abuse scandal.

But it is wishful thinking to see this as a final defeat of the Blairites, not least as shown in the symbolism of Watson’s departure taking place on the same day that the prominent left-wing Corbynista MP, Chris Williamson, was debarred as a Labour candidate in December.

More profoundly, the ruling class will not so lightly give up the chance to reassert the control of the Labour brand it exercised under New Labour, and to snuff out the possibility Corbyn’s leadership gives for a revival of working-class political representation through the Labour Party.

The Blairites and their cross-party parliamentary collaborators, and the capitalist strategists they discuss with, face a dilemma.

To organise a coalition in the immediate aftermath of the election, or any other formal vehicle of realignment, would use up prematurely their weapon for splitting the parliamentary Labour Party, before the experience of a Corbyn-led government.

While it would forestall that immediate possibility and leave Jeremy Corbyn at the head of a smaller parliamentary group, it would create new opportunities for Labour to develop as a mass workers’ party vying for power in the future, within which a clear socialist programme could find an ever-wider audience.

The Socialist Party would do everything to assist in this necessary transformation, including applying to affiliate, once again.

The exact parliamentary arithmetic arising from December’s poll will affect the tactics adopted. The capitalists would only opt for a realignment coalition if the possibility was there to change the rules of the game – David Miliband’s ‘democratic reboot’ – and introduce proportional representation, a historic shift for British capitalism.

They last considered this seriously in the 1970s – reflecting, in particular, on the experience in Chile of Salvador Allende’s presidential election victory, initially with a 36% vote share – as a means to stop a possible Tony Benn-led left Labour government coming to power on the basis of similar ‘minority support’.

The other option if Labour is the largest party is for the Blairites to delay a split and, instead, to work for a period to sabotage a Corbyn-led government from the Labour benches.

What is clear is that, by not completing the transformation of the Labour Party – the mandatory reselection of MPs, restoring the role of the unions democratically exercised, readmitting expelled socialists, including the Socialist Party, in a modern version of Labour’s original federal structure etc., – the Blairites have been left in a position where they can consider such wrecking options.

More than a hundred Labour candidates took part in previous attempted coups against Jeremy Corbyn, including Margaret Hodge, who moved the vote of no confidence in him in the parliamentary party that began the 2016 leadership election.

She survived the ‘trigger ballot’ in her local party and is standing again. In fact, as the Blairite Labour First organisation triumphantly boasts, and the left-wing journalist Owen Jones lamented in The Guardian (26 September), “not a single MP has been deselected, leaving the politics of most of the parliamentary party at odds with the membership” – and a Corbyn premiership.

Not just Corbyn and McDonnell, but the leadership of the Momentum group and some left trade union leaders, bear the responsibility for not seizing the opportunities of the past four years.

Even if there is a parliamentary majority of Labour MPs after 12 December, Corbyn would effectively be faced with the prospect of heading a minority government.

But the situation can still be retrieved by decisive leadership to mobilise the working class.

What needs to be done?

The last general election held in December before this year’s contest was in 1923, when the Conservative Party under Stanley Baldwin won the most seats – 258 MPs compared to 191 for Labour and 158 Liberal MPs – but lost its overall majority.

Baldwin’s King’s Speech programme for government was defeated and, after Labour’s national executive voted that the party should form a government alone if the opportunity arose and not enter into coalition, a minority administration was formed with Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister.

MacDonald has earned particular notoriety for his betrayal of the labour movement through the formation of the national government with the Tories in 1931, but in 1924 the Labour Party – then, a new workers’ party which had emerged on the back of the attacks on the unions in the first decade of the twentieth century – had not been in power before.

The chancellor Philip Snowden, who also gained notoriety for his role in 1931, had just months before the formation of the 1924 administration moved a bill in parliament calling for the “supersession of the capitalist system”, albeit “the gradual supersession” through reforms.

But here was an opportunity to test out such ideas in practice in what was then, even if the USA was closing in fast, still the greatest imperialist power on the globe.

Leon Trotsky, the leader with Lenin of the October 1917 Russian revolution, commented at the time on the events unfolding in Britain: “How will the ‘Labour’ government proceed? If it does not have a majority in parliament that does not mean its situation is totally hopeless.

“There is a way out; one need only have the will to find it. Suppose MacDonald said this: ‘To our shame, our country has to this day a kind of august dynasty that stands above democracy and for which we have no need’…

“What if he added, ‘We are going to take their lands, mines, and railways, and nationalise their banks’… [and] with the resources released… we are going to undertake the construction of housing for the workers’, he would unleash tremendous enthusiasm…”

“If MacDonald walked into parliament, laid his programme on the table, rapped lightly with his knuckles, and said, ‘Accept it or I’ll drive you all out’ (saying it more politely than I’ve phrased it here) – if he did this, Britain would be unrecognisable in two weeks. MacDonald would receive an overwhelming majority in any election…”

“In general, he can win the hearts of millions of workers only by a courageous policy, and then no one could turn him out by parliamentary tricks”. (‘On the Road to the European revolution’, 1924)

What better model is there for Jeremy Corbyn, and the whole workers’ movement, for all the eventualities that may face him if he is in a position to form a government on 13 December?

Trotsky did not write with the expectation that MacDonald would act decisively in the workers’ interests – “he is conservative, in favour of the monarchy, private property and the church”.

But the experience even of a minority government being “pushed by the Liberals and Conservatives” – and in the events ahead, the Blairites – “in turn pushes the British workers towards the revolutionary road. Such will be the final result of this historic experiment”.

That is why the pessimistic mantra of those on the left that this general election is a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity for change is wrong.

Against the backdrop of a new international upsurge of struggle, whatever the outcome of December’s election and its aftermath it will represent the beginning of a new protracted period of crisis for capitalism. In which the working class will test out different alternatives as it finds the road to a Marxist understanding and a programme that can defeat capitalism and begin the construction of a new socialist society.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |