On 3 April Sweden’s Radio P3’s news programme ran an article relating reports from anonymous medical workers who claimed that covid-19 patients who would have survived with intensive care were being denied it. Johan Styrud of the Swedish doctor’s union, the Läkarförbund, went on record saying, “people will die who might otherwise have survived if they received adequate care.” Oddly this shocking report received no attention, neither corroboration nor refutation, elsewhere in the Swedish press, and has likewise been ignored worldwide. Are Sweden’s hospitals leaving coronavirus patients to die who might have lived?

An analysis of the evidence shows the claims are likely true. Many of the 2,000 deaths suffered, so far, in Sweden were preventable, and medical workers in Sweden have been put in the horrific position of denying care to patients who could have been saved.

Structural shortages

Advocates of the Swedish response note how Sweden, unlike the UK, has not had a shortage of ventilators used to provide life support to covid-19 patients. Certainly, the workers of Sweden’s Getinge Group medical company have heroically increased production, and Sweden is a net exporter of ventilators. Discussing the availability of ventilators is, however, a distraction from other, more critical shortages.

For years, before 2020, health advocates in Sweden identified the shortage of hospital beds in the country as an ongoing problem. In 2019, Sweden had a total of just 526 intensive care beds for a population of over 10 million and among the lowest number of beds per capita in Europe. Before the coronavirus outbreak, it was already common practice for patients in Sweden to be sent to neighboring Finland for some forms of care, and shortages of beds and hospital equipment were regularly reported in the media. Discrimination against the elderly and chronically ill in access to care was already recognized as a consequence of ongoing privatization.

Capacity is expanding, slowly. Sweden’s army opened a 600-bed field hospital in Stockholm’s Älvsjö convention center on 6 April. But only a few of these are intensive care beds, and the facility will reach its full capacity only slowly. Moreover, the experience in the United States and United Kingdom has been that these emergency hospitals are heavily–underused and difficult for ordinary people to access.

However, no matter how many beds are built, there must be qualified staff to handle them. Ever since the beginning of heath care privatization over twenty years ago Sweden has suffered an ongoing shortage of medical staff. Nurses at the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm’s main hospital, are working twelve–and–a–half hour shifts. Furloughed airline and hotel workers have been re–tasked as hospital support workers under an emergency regime. Stockholm health care director Björn Eriksson has begged recently–retired doctors and nurses to return to work. “We will take all the help we can get,” said Eriksson.

These shortages were entirely preventable. Last year Karolinska Hospital alone cut 1100 jobs–550 administrators, 250 doctors and 350 nurses’ assistants–when the city government refused to fully fund their operational needs. Doctors warned at the time that patient safety was being compromised by the cuts and that “awful things are going to happen…everyone is terrified what is going to happen here.”

Catastrophe by memorandum

By mid-March, three weeks into Sweden’s coronavirus outbreak, the national health care system was already strained and patient safety was being “trampled over” as hospitals ran out of space. At the end of the first week of April Sweden’s intensive care beds reached capacity.

It is in this situation of overloaded staff and facilities that Karolinska Hospital made fatal utilitarian decisions. According to Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, by 4 April managers at Karolinska had told ICU doctors in an internal message, “We will need to end intensive care for a large number of patients that we would continue to have cared for in normal situations and with unlimited resources.” In an undated memorandum seen by newspaper Aftonbladet, sometime before 9 April, Karolinska managers made a policy choice to deny intensive care to some coronavirus patients care based on “biological age”–a combination of physical age and pre-existing health conditions. Under the terms of the memorandum, people aged 80 and over are automatically denied treatment.

Karolinska managers were following guidance issued by the Swedish government at the beginning of April which opened the door for this form of triage. In the guidance, they explicitly allow but do not require, discrimination based on biological age in refusing intensive care for COVID-19 patients.

At the time, Stockholm’s regional director of health denied anyone had been denied intensive care, saying there were still ICU beds available. Over the following weeks, though, the pandemic in Sweden would continue to worsen.

Statistical evidence

As of this writing, no health official has gone on record admitting patients in Sweden are being turned away from intensive care. However, statistics published by Sweden’s health authorities suggest a near-certainty that the Radio P3 News claims are true.

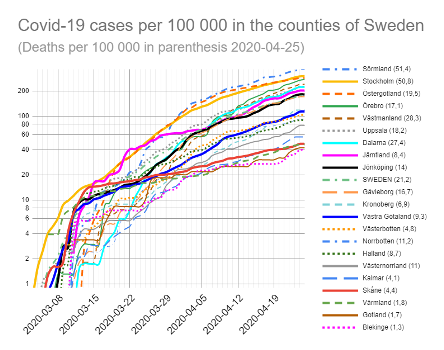

While Swedish regional health authorities refuse to give hard figures as to how many new intensive care beds have been created, the Swedish Intensive Care Registry (SIR) reports that the number of COVID patients in intensive care levelled off at less than 550 around 14 April–a number that matches well with the known number of beds plus marginal expansion. By 20 April, all regions of Sweden, not just Stockholm, were reaching their intensive care limits.

At the same time, data from the Folkhälsomyndigheten, the Swedish Public Health Agency, says the total number of coronavirus infections has continued to grow exponentially throughout March and April. Furthermore, changes to testing requirements mean that the fraction of diagnosed coronavirus infection requiring ICU treatment has increased, not decreased, over the past month.

The SIR data also say that it takes an average of 11 days for someone diagnosed with coronavirus to require ICU treatment. Taking this into consideration, we can determine what fraction coronavirus patients have received ICU care, as a function of time. The results are stark. Until 3 April, a person diagnosed with coronavirus had a 30% chance of receiving ICU treatment for covid-19. After 3 April, the chance that a patient will get ICU care drop immediately and dramatically to below 10%. There have been no reports of changes in the effectiveness in treatment or the progression of the virus, leaving one conclusion: since the beginning of April, two-thirds of the Swedish covid patients who need intensive care are not getting it.

As of this writing, nearly two thousand people have died in Sweden of covid-19, far more than in all the other Nordic countries, combined. Over 75% are aged 70 years or older. The official position of the Swedish government is to call Sweden’s libertarian attitude toward the novel coronavirus a success. Capitalist media around the world hail the continuation of “normal life”–i.e. the uninterrupted advancement of exploitation and profiteering–and now argue that decreasing rates of new infections in Sweden justify the Swedish state’s strategy.

Doctors and nurses must make life-or-death decisions every day for patients. In crisis situations, they may have to make decisions of triage, to sacrifice one patient in order to treat another with better chances of surviving. They cannot be blamed for implementing managerial policies in an impossible situation.

The “flattening the curve” strategy proposed by the WHO does not greatly reduce the number of people who will eventually get coronavirus. The entire point of the strategy is to lengthen the outbreak in time but reduce it in intensity, specifically to avoid the overloading of hospitals and health care infrastructure. By slowing the growth of the number of infections, more of the population can access to hospitals, particularly intensive care.

Sweden’s officials must have known a strategy of letting the virus run wild would cause their health system to become overloaded. Meanwhile, as the evidence builds that coronavirus infection does not guarantee resistance, the “herd immunity” strategy–which Sweden at first denied it was pursuing but now embraces–has been shown to be a dead end. Those people who died from lack of access to intensive care died for nothing.

The crisis in Swedish health care was avoidable. By isolating people in order to slow the spread of the disease, by fully funding hospitals, by never embarking on privatization and cutbacks in care and the first place, potentially hundreds of lives in Sweden could have been saved already. Instead, like all those who died needlessly of polio because western governments would not accept a Soviet vaccine, like all those who died of AIDS because governments of the rich saw greater profit in homophobia and racism than in saving the lives of LGBT and African workers, the dead in Sweden join the ever-growing host of those murdered by the malevolent neglect of the market.