The following text by Pascal Grimbert was published as a short pamphlet by Gauche Révolutionnaire (CWI in France), in March 2011, to mark the 140th anniversary of the Paris Commune.

socialistworld.net

Historical and political summary

The revolutionary experience of The Commune was very short, between the insurrection of 18 March and the end of the Week of Blood of 28 May 1871. But its origins took root quite sometime earlier, in the context of the degenerating ‘Second Empire’ of Napoleon III, during which the working class started to organise and socialist ideas started to spread.

The war that Napoleon III started with Bismarck’s Prussia in July 1870 led to a total defeat. On the 4th of September, the Republic was proclaimed and a provisional government was set up. But the Prussian army occupied a large part of northern France and continued its progress until 1871. The 19th September 1870, was the beginning of the siege of Paris.

The Parisian people took up arms, organising themselves within the National Guard. The armistice with Prussia was signed on the 28th of January 1871 and elections took place on the 8 February, establishing a monarchist, bourgeois and reactionary national assembly. Only Paris and large cities had Republican representatives.

Economic and social context

The period after the defeat of the 1848 revolution was one of the huge development of industrial and commercial capitalism and at the same time, the working masses were held in deep poverty. The character of the bourgeois state appeared more and more clearly. In the 19th century, transmitted from the Middle Ages, the centralised power of the state developed, with its component organs present everywhere: permanent army, police, civil service, clergy and magistrates. Due to the development of class conflict between Capital and Labour, the power of the state took on more and more the character of a public power whose ends were social enslavement, an apparatus of class domination.

After every revolution, that marks progress in the class struggle, the purely repressive character of the power of the state becomes more and more open. After the revolution of 1848-1849, the power of the state became the engine of the national war of Capital against Labour. The Second Empire only consolidated it. “The direct antithesis to the Empire was the Commune. The cry of ‘social republic,’ with which the (1848) February Revolution was ushered in by the Paris proletariat, did but express a vague aspiration after a republic that was not only to supersede the monarchical form of class rule, but class rule itself. The Commune was the positive form of that republic.” (K. Marx, The Civil War in France)

However, in 1871, as Lenin analysed it, the proletariat did not constitute the majority of the people in any European country. It could only be a question of a victorious revolution if it brought together in the same movement the proletariat and the peasantry. We will see that the Commune was not able to succeed in achieving this aim.

Revolt

Nevertheless, facing the threats of restoration and Prussian occupation, the people of Paris organised themselves – through the National Guard and its Central Committee. The new National Assembly decided to withdraw the pay of the National Guards and lift the moratorium on rents which had been decreed during the war, adding to the discontent.

Thiers, at the head of the government, wanted to disarm the National Guard that had regrouped its weaponry and canons (paid by the contributions of the Parisian people) in the working-class neighbourhoods of Belleville, Montmartre and Buttes Chaumont. On the 18 March, Thiers sent the army to take back the canons. The National Guard and the Parisian proletariat opposed this, putting up barricades and fraternising with the soldiers. Two generals – Lecomte and Thomas – were executed. The Central Commitee of the National Guard took power. The government and the army retreated to Versailles.

The Central Committee organised elections for 26 March to give power to the new city council: the Paris Commune. The eighty-five elected representatives had, for the most part, humble origins – employees, artisans, small businesspeople etc. and, above all, 25 workers, symbolising the development of the working class in this period.

Four major political trends were represented. The Republican Jacobins were in the majority. The Internationalists of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) had seventeen representatives, including Leo Frankel, Eugene Varlin and Benoit Malon. The Blanquists and the Moderate Republicans refused to take their seats.

Internationalists

The IWMA, created in 1864, was poorly represented in France. The movement there had to rebuild itself after the repression of the 1850s under the imperial dictatorship of Napoleon III, following the revolution in 1848. Its branches in France outside Paris – in Lyon, Marseille, Rouen – were relatively small. (In Lyon, for example, there were 500 members.)

The International at this time was afflicted by dissent between Marxists and anarchists. Marx was calling on French workers to methodically build their class organisations before considering carrying out an uprising. Bakunin, a refugee in Switzerland, came to France and conducted agitation in Lyon in 1870 where, that year, he even took hold of the City Hall where he proclaimed the abolition of the state. But, as Marx ironically pointed out, “The state, in the shape and form of two companies of the bourgeois National Guard, entered by a door which had inadvertently been left unguarded, cleared the hall, and forced Bakunin to beat a hasty retreat back to Geneva!”

Bearing out Marx’s words, the IWMA was unable to play a decisive role in the insurrection and the way the Commune operated. Nevertheless, it was the Internationalists who, during the siege of 1870, led the Arrondissement (District) Vigilance Committees and their Central Committee. In the legislative elections of February 1871, two of them, Malon and Tolain, were elected. But the Internationalists hardly took part in the setting up of the Central Committee of the National Guard which effectively led the insurrection.

Meanwhile, reaction was organising. The Versaillais (forces loyal to the Versailles-based, Thiers-led regime) started the bombardment of Paris on the 2nd of April. The attempts by the ‘Communards’ to fight back failed. The Commune is isolated, the attempts to build Communes in other big French cities like Lyon and Marseilles are very quickly and ruthlessly repressed. Enormous disagreements arise amongst members of the Commune and at the heart of the Committee for Public Safety. There are disagreements over political and economic decisions, in particular over military tactics, to which are added disciplinary problems in the ranks of the National Guard.

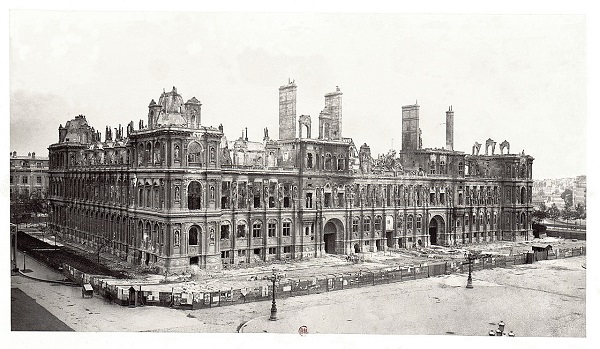

The 21st of May opens the Week of Blood, with the entry of the Versailles troops into Paris. The repression is ferocious, bloody and merciless. The bourgeoisie wants payment with blood for the revolution that has rocked it; it aims to discourage any new revolt of workers.

The Communards defend themselves street by street, barricade by barricade, but retreat. On the 27th of May, the last of the Communards are felled by the bullets of Versailles at the Mur des Federes in the Pere-Lachaise cemetery. More than 30,000 dead – men, women and children. Around 40,000 were made prisoners, of whom many are condemned to death or deported to the New Caledonia colony in the South Pacific.

This was an enormous defeat for the proletariat. But it took less than ten years for the French workers’ movement to rebuild itself. The Commune would definitively mark the pre-eminence of Marxism at the heart of this workers’ movement, demonstrating the dead-end of socialist utopian theories, anarchist or Proudhonist, like those of the Blanquist activists. The IWMA was decimated in France after the Commune – a defeat both in France and internationally that was an important factor in the IWMA dissolving in 1876. But Marxist ideas would gain a majority, and, within the workers’ movement, especially after the later setting up of the Second Socialist International.

II

The work of the Commune

Immediately after it was set up, the Commune put in place revolutionary measures, radical and advanced (particularly in the context of the reactionary bourgeois society at the time). Firstly, emergency measures:

-Moratorium on unpaid rents

-Requisition of unoccupied housing

-Rescheduling of commercial debt

-Restitution of objects pawned in pawnshops

-Introduction of a minimum wage

-Prohibition of fines taken from wages

-Prohibition of night work for bakery workers

Symbolic measures, such as the demolition of the Vendome column, erected to the glory of Napoleon I and symbolising nationalism and imperialism, and re-establishing the revolutionary calendar in place between 1793 and 1805.

But, most importantly, measures profoundly reorganising society:

– Women’s right to vote (only reinstated in bourgeois France in 1947)

– Separation of Church and State

– Prohibition of night work for children

– Abolishment of military conscription and disbandment of the permanent army: it is the armed people themselves who assure their own defence, elect their own officers.

– State companies and those of the city are “communalised”, their management is given to the workers who work in them. They elect their workplace delegates who can be recalled. The workplaces abandoned by the bosses are confiscated and handed over to the workers, organised into production cooperatives. Workshops are created for the unemployed.

– It is the district committees that directly manage administration and public services, such as schools (the Commune installs free, secular and compulsory education, including for girls), health, the post, and also public lighting, funds and firefighters.

– All functionaries, from members of the Commune to the simplest employee, must receive a worker’s wage.

– Police and court officials alike were under the control of the people and were also subject to recall at any moment.

But the Commune neglected certain essential measures, such as taking control of the gold which was deposited at the Bank of France. The influence of “legality” on a large part of the members was a handicap when facing Thiers’ Versaillais, who had neither scruples nor any sense of morality. Too often this legalistic concern led many members of the Commune to adopt a conciliatory attitude towards the government of Thiers. It was because of this that Longuet, who later, in exile, became a Marxist, could, on March 30th 1871, regret, “The deplorable misunderstanding which, in the days of June [1848], set two classes one against the other” or that Jourde, at the session of the Commune on the 25th of April, had been able to rejoice that the Commune had “never infringed on property”.

The Commune was a period of freedom for the proletariat. There reigned, at one and the same time, a climate of festivity, despite the difficulties, and of commitment on the part of all. Discussions, debates and newspapers multiplied. Women took an important place in society. All took their part of responsibility in the daily management of society. What a contrast with the France of the Restoration, or the moralistic and colonialist Third Republic. With the Commune, the working class showed that it was not only the sole revolutionary force, but also and at the same time, the sole progressive force for human society.

The essential points to hold on to:-

– Abolition of the permanent army and its replacement with the people in arms.

– Replacement of parliamentarism with “a working body, at the same time executive and legislative”.

– Workers’ wages and recall of all officials and elected representatives.

III

What political lessons to draw from the experience of the Commune?

The Commune has been a good example for all proletarian revolutionary movements. It illustrated how to put in place a new political organisation of society by the workers themselves, in the service of their own interests. But it also showed its limits, due both to the objective conditions of the development of the class struggle and the subjective conditions of the political organisation of the working-class. That is to say the working-class was still in the process of formation, the economic organisation of society had not yet become that of big concentrated industry and workers were not yet organised in mass political organisations capable of leading its struggles.

As early as September 1870, Marx had addressed a warning to the Parisian workers against the dangerous character of an insurrection against the bourgeois government. “The French working class moves, therefore, under circumstances of extreme difficulty. Any attempt at upsetting the new government in the present crisis, when the enemy is almost knocking at the doors of Paris, would be a desperate folly … Let them calmly and resolutely improve the opportunities of republican liberty, for the work of their own class organisation”. This did not prevent him from, in March 1871, saluting and supporting the Commune and the insurrection of the workers who were “storming heaven” in the situation imposed on them by the actions of the Thiers government and the bourgeoisie. After this unconditional support, Marx set about drawing the lessons of the experience of the Commune – lessons enriched and developed later by Lenin, above all on the subject of the state, and by Trotsky, particularly on the subject of the party.

Breaking the bourgeois state apparatus

The great importance of the revolutionary experience of the Commune was demonstrated by the fact that it inspired Marx to make the only change he judged necessary to the Communist Manifesto. With Engels, he declared in the preface of the 1872 edition, that their programme had, “In some details become antiquated: “One thing was especially proved by the Commune, viz., that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes”.

During the Commune, Marx was already writing: “If you look at the last chapter of my Eighteenth Brumaire you will find that I say that the next attempt of the French revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it, and this is essential for every real people’s revolution on the Continent. And this is what our heroic Party comrades in Paris are attempting. What elasticity, what historical initiative, what a capacity for sacrifice in these Parisians!”

Until then, Marx only gave an abstract idea of what would replace the bourgeois State. In the Manifesto, he spoke of, “the organisation of the proletariat as the ruling class” or of the “conquest of the democracy”. The Commune provided a concrete experience that Marx analysed.

During the 19th century, the power of the state developed in France until it became, after the revolution in 1848, more and more, “the national war machine of Capital against Labour”. The measures taken by the Commune were in complete contradiction to the organisation of the bourgeois State. The change from bourgeois democracy to proletarian democracy could only (and would only) be done by replacing the State, – “special power” whose role is the oppression of a class – with the general power of the majority of the people, workers and peasants. The measures taken by the Commune went in this direction:

-Suppression of the permanent army and its replacement by the people in arms

-Responsibility, election and recall of those elected (workers or representatives of the working-class) and public servants, even in the police or judiciary.

-Bringing the income of all civil servants onto the level of a workers’ wage, thus putting an end to all financial privilege – the source of servility and careerism

This reorganisation was done very simply, and while most of the leaders of the state’s apparatus and the public services had fled with the Versaillais, the workers had been perfectly capable of functioning without the “specialists” who were so lavishly paid. “The Commune made that catchword of bourgeois revolutions – cheap government – a reality by destroying the two greatest sources of expenditure: the standing army and state bureaucratism”.

Another huge break with the past carried through by the Commune was ending bourgeois parliamentarianism. A few passages by Marx in his work, ‘The Civil War in France’.

“The Commune was to be a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time.”

“The multiplicity of interpretations to which the Commune has been subjected, and the multiplicity of interests which construed it in their favour, show that it was a political form susceptible to expansion, while all the previous forms of government had been emphatically repressive. Its true secret was this: It was essentially a working class government, the product of the struggle of the producing against the appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labour.”

“Instead of deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to misrepresent the people in Parliament, universal suffrage was to serve the people, constituted in Communes, as individual suffrage serves every other employer in the search for the workmen and managers in his business.”

We can clearly see what role the elected representatives should play according to Marx. The bourgeois parliamentarianism, corrupt and gossiping (the parliamentary “lapdogs” as Lenin said and who still exist) need to end, along with the division of labour between legislative and executive and the privileged positions for members of parliament. In its place, and that is what the Commune did, it needed to create bodies accountable to those who elected them. It is not a question of getting rid all representative bodies, but it is necessary from the start to break the administrative machine of the bourgeois state and immediately put all of the administration at the service of, and under the control of, the proletariat. It is workers who should organise society and production by controlling the state’s power, including by arms.

To quote Lenin, “The Commune is the first attempt made by a proletarian revolution to smash the bourgeois state machine; it is the political form “at last discovered”, by which the smashed state machine can and must be replaced.”

A workers’ party

One of the biggest handicaps of the Commune, apart from the objective conditions of its seizure of power, was the absence of an organised and conscious political leadership that would have allowed it to make decisions and apply a clear programme. Marx, shortly before the Paris insurrection, counselled the communards not to rise up, but to create an organisation. The IWMA was far from a majority within the commune, and at its centre, the Marxist socialists were only a handful. Trotsky wrote:

“The Parisian proletariat had neither a party nor leaders to whom it would have been closely bound by previous struggles. The petty-bourgeois patriots who thought of themselves as socialists and sought the support of the workers did not really have any confidence in themselves. […] Their socialist phraseology is nothing but a historic mask that permits them to impose themselves upon the masses.

“The workers’ party – the real one – is not a machine for parliamentary manoeuvres; it is the accumulated and organised experience of the proletariat. It is only with the aid of the party, which rests upon the whole history of its past, which foresees theoretically the paths of development, all its stages, and which extracts from it the necessary formula of action, that the proletariat frees itself from the need of always recommencing its history: its hesitations, its lack of decision, its mistakes.

“The proletariat of Paris did not have such a party …”

“The Central Committee of the National Guard is in effect a Council of Deputies of the armed workers and the petty bourgeoisie. Such a Council, elected directly by the masses who have taken the revolutionary road, represents an excellent apparatus of action. But at the same time, and just because of its immediate and elementary connection with the masses who are in the state in which the revolutionary has found them, it reflects not only all the strong sides but also the weak sides of the masses, and it reflects at first the weak sides still more than it does the strong: it manifests the spirit of indecision, of waiting, the tendency to be inactive after the first successes.

“The Central Committee of the National Guard needed to be led. It was indispensable to have an organisation incarnating the political experience of the proletariat and always present-not only in the Central Committee, but in the legions, in the battalion, in the deepest sectors of the French proletariat. By means of the Councils of Deputies – in the given case they were organs of the National Guard – the party could have been in continual contact with the masses, known their state of mind; its leading centre could each day put forward a slogan which, through the medium of the party’s militants, would have penetrated into the masses, uniting their thought and their will …”

“The party does not create the revolution at will, it does not choose the moment for seizing power as it likes, but it intervenes actively in the events, penetrates at every moment the state of mind of the revolutionary masses and evaluates the power of resistance of the enemy, and thus determines the most favourable moment for decisive action. This is the most difficult side of its task. The party has no decision that is valid for every case. Needed are a correct theory, an intimate contact with the masses, the comprehension of the situation, a revolutionary perception, a great resoluteness. The more profoundly a revolutionary party penetrates into all the domains of the proletarian struggle, the more unified it is by the unity of goal and discipline, the speedier and better will it arrive at resolving its task.

“The difficulty consists in having this organisation of a centralised party, internally welded by an iron discipline, linked intimately with the movement of the masses, with its ebbs and flows. The conquest of power cannot be achieved except on the basis of powerful revolutionary pressure from the toiling masses. But in carrying it out, the element of preparation is entirely necessary. The better the party understands the conjuncture and the timing, the better the bases of resistance are prepared, the better the forces and the roles are shared out, the surer will be the success and the fewer victims it will cost. The correlation of a carefully prepared action and a mass movement is the politico-strategical task of the taking of power”. (In this lies the radical difference with Utopian socialists and Blanquists).

“The comparison of March 18, 1871, with November 7, 1917, is very instructive from this point of view. In Paris, there is an absolute lack of initiative for action on the part of the leading revolutionary circles. The proletariat, armed by the bourgeois government, is in fact in charge of the city, has all the material means of power at its disposal – cannon and rifles, but it is not conscious of its power. The bourgeoisie makes an attempt to retake the weapon from the giant: it wants to steal the cannons of the proletariat. The attempt fails. The government flees in panic from Paris to Versailles. The field is clear. But it is only the next day that the proletariat understands that it is the master of Paris. The ‘leaders’ are behind events, they recognise them when they are already accomplished, and they do everything possible that blunts the revolutionary edge.

“In Petrograd, events developed differently. The party moved firmly, resolutely to the seizure of power, having its men everywhere, consolidating each position, extending the gap between the workers and the garrison on the one side and the government on the other. […]

“ The months of August, September and October see a powerful revolutionary shift. The party profits from it and considerably augments its points of support in the working class and the garrison. Later, the harmony between the conspiratorial preparations and mass action takes place almost automatically. The Second Congress of the Soviets is fixed for November 7th. All our preceding agitation had to lead to the seizure of power by the Congress.”

Later in this article, Trotsky also made a special analysis of the French workers’ movement – that can be considered relevant for today.

“We can thus thumb through the whole history of the Commune, page by page, and we will find in it one single lesson: a strong party leadership is needed. More than any other proletariat has the French made sacrifices for the revolution. But also more than any other has it been duped. […]

“The temperament of the French proletariat is revolutionary lava. But this lava is now covered with the ashes of scepticism – the result of numerous deceptions and disenchantments. Also, the revolutionary proletarians of France must be severer towards their party and unmask more pitilessly any non-conformity between word and action. The French workers have need of an organisation, strong as steel, with leaders controlled by the masses at every new stage of the revolutionary movement.”

Earlier, Trotsky wrote that: “The hostility to capitalist organisation – a heritage of petty-bourgeois localism and autonomism – is without a doubt the weak side of a certain section of the French proletariat. Autonomy for the districts, for the wards, for the battalions, for the towns, is the supreme guarantee of real activity and individual independence for certain revolutionists. But that is a great mistake that cost the French proletariat dearly. […]

“The tendency towards particularism, whatever the form it may assume, is a heritage of the dead past. The sooner French communist-socialist communism and syndicalist communism emancipates itself from it, the better it will be for the proletarian revolution.”

It is the relevance of these analyses which drives us to agitate for the building of a new workers’ party with a socialist programme.

The Commune is a lesson of courage, but it shows that the revolution will not be improvised, that the working class needs an independent organisation that can both serve and lead – a party organised on a socialist programme.

The final point: why does the proletarian dictatorship constitute at the same time the means of the destruction of the capitalist society and the start of a communist society. To quote Lenin, “It is still necessary to suppress the bourgeoisie and crush their resistance. This was particularly necessary for the Commune, and one of the reasons for its defeat was that it did not do this with sufficient determination. The organ of suppression, however, is here the majority of the population, and not a minority, as was always the case under slavery, serfdom, and wage slavery. And since the majority of people itself suppresses its oppressors, a ‘special force’ for suppression is no longer necessary! In this sense, the state begins to wither away. Instead of the special institutions of a privileged minority (privileged officialdom, the chiefs of the standing army), the majority itself can directly fulfil all these functions, and the more the functions of state power are performed by the people as a whole, the less need there is for the existence of this power.”

To conclude and to show once more the relevance for today of the lessons taken from the Commune, a quote from Engels’ ‘Introduction to the Civil War in France’ by Karl Marx (1891): “The social-democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome terror at the words: the dictatorship of the proletariat. Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the dictatorship of the proletariat.”