A hundred and fifty years ago, on 18 March 1871, the armed proletarians of Paris set out to “storm heaven” (as Marx put it) and created the very first embodiment of a state ‘by and for’ the workers. It is a revolution rich with a thousand lessons for those who want to transform the world.

The beginning of the revolutions of the modern world

The French Revolution from 1789 to 1796 had swept away the old feudal world. Frightened by what it had set in motion, a large part of the bourgeoisie sought a form of authoritarian regime, first with the adventurer Bonaparte and then through the old aristocratic class. But with the revolution, France had entered at full speed into capitalism which, by developing, by multiplying factories and workshops, developed the mortal enemy of the bourgeoisie: the working class. The whole 19th century was marked by a succession of revolutions in which the working class increasingly took on a major role.

Marx and Engels had barely finished writing the Communist Manifesto when, in early 1848, a wave of revolutions swept through Europe, from Poland to France, passing through Germany. But in these revolutions, the bourgeoisie remained in control, aided by the illusions propagated by ‘socialists’, such as Louis Blanc, who participated in the capitalists’ government. The utopia of a “social republic” to be governed by the class most hostile to it, the bourgeoisie, was drowned in the blood of the April-June repression of 1848, and the final assault on the insurrectionists who resisted heroically against General Cavaignac’s troops.

With between 10,000 and 15,000 dead, Marx and Engels had already pointed to this terrible lesson that in the Communist Manifesto – that the working class must forge its own party to fight its exploiters and oppressors.

The coup d’état of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

However, the liberal bourgeoisie had itself sealed its own fate by crushing the workers. The big bourgeoisie wanted order and, above all, a government that was entirely prepared to implement policies in the interests of the big financiers and industrialists. The coup d’état of 2 December 1851 would be the victory of the Party of Order in the face of a completely unorganised resistance from a republican camp that had thought it could deal with Louis-Napoleon.

A year later, the Empire would be founded with a policy of colonial expansion and the development of large private corporations. Napoleonic power established an authoritarian and repressive regime, accumulating against it a growing hatred on the part of both workers and the democrats. But the latter feared the revolutionary people even more.

In the end, it was the very contradictions of the regime – mixing colonial adventures and war-making policies in Europe, far beyond its capacity – that led to its downfall. One last war against Prussia will become a rout and opened the way to a new insurrection which will proclaim the Republic on the 4th of September 1870.

Paris in revolt

The bourgeoisie would have preferred a constitutional monarchy but the Parisians left them no choice. Once again, Marx advised the proletarians to beware of this bourgeoisie and to form their own party. For the former was plotting, in connection with the Prussian military occupiers, and was leaving Paris besieged and defenceless. In March, at the instigation of its representative, Thiers, it even wanted to deprive the people of the Montmartre district of the cannons they had for defence against the enemy. This was too much. On 18 March, workers, craftsmen and shopkeepers rose up and executed the senior officers who were preventing them from keeping their artillery, and were supported by the rank and file soldiers. Thiers refused to give way to the resistance of the Paris people, attempting a trial of strength.

The first workers’ government

On the evening of 18 March, with an uprising in the east and north of Paris, the Thiers government fled to Versailles. Power had fallen into the hands of the proletariat without it being fully aware of it: the Communard revolution had begun. And it was with enthusiasm, energy and creativity that the communards organised the new society which could come into being thanks to them.

On 26 March, elections were organised across the city by the central committee of the National Guard and a Paris Commune government was formed. In spite of the famine, there were 229,000 people who voted (a turnout similar to previous peacetime elections), with a democratic list system, proportional representation and no restrictions on voting. A majority of 60 out of the 85 elected members who attended the municipal assembly came from the world of work (workers, craftsmen, etc.). The first workers’ government in history had been born and was celebrated with a huge demonstration on the square in front of the town hall on 28 March.

The assembly was representative of the various revolutionary currents which existed at the time. Twenty were neo-Jacobins (supporters of the Constitution of 1793, not yet understanding the new role of the proletariat). Nine were supporters of Blanqui (who was still in prison and could not take his seat) and fifteen of them were Internationalists (members of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), including several supporters of Marx). If all of them were revolutionaries, (except for the fifteen who were in favour of conciliation with Thiers, who quickly resigned), only a minority around the Internationalists had a class analysis: Malon, Frankel, Longuet, and Varlin, for example. The red flag became the flag of the Commune.

Measures taken by the Commune

From the day after it was installed in the Hôtel de Ville, on 28 March, the Commune began its immense political work. Marx speaks of the Commune as the “self-government of the producers”. The universal right to vote (admittedly still only for men) was established. Officials were elected everywhere, including in the National Guard, and if any representative betrayed the decisions, they could be dismissed. An elected official could be of foreign nationality because the Commune recognised itself as the “universal republic”. The pay of elected representatives was capped at a maximum of an average worker’s wage.

From the very first day, the elected representatives of the Commune established the separation of church and state. Education was no longer in the hands of the Church; it was made public and the curriculum was established jointly by teachers, parents and pupils. Education was to be made liberating – beginning at birth and responding to the needs of children: nurseries with gardens, toys, aviaries, etc. The ‘New Education’ movement, made up of teachers, aimed to establish a secular, compulsory, free schooling, for all. The first vocational schools were created so that each child could choose a profession. Orphans were “taken in charge” by society in boarding schools up to the age of 18. Items deposited at pawn shops (which were squeezing the necks of workers and small craftspeople with extortionate rates) were returned to them.

The Commune also organised supplies (with Paris still under siege by the Prussian army) and made a list of the workshops closed by the bosses. On 16 April, Frankel organised the reopening of some of them to create a public federation of workshops and they were able to elect delegates to manage without bosses. Employment offices (previously run by the bosses and the police) were closed. Night work for apprentice bakers was prohibited.

Public services, such as the post office and health care, were to be managed by district committees. Municipal butcher services, bread supply… were organised to ensure the distribution of food. Politically, there was a profusion of newspapers – more than 70 – and political clubs.

Revolutionary women in the Commune

Women played a very important role during the Paris Commune, and their revolutionary organisations are a testimony to this. Elisabeth Dmitrieff, a Russian militant, arriving at the end of March 1871, was sent from London by Karl Marx, when she was barely 20 years old. Together with Nathalie Le Mel, also an IWA member, she founded the “Union of Women for the Defence of Paris and the Care of the Wounded” on 11 April. They were both members of the central committee. For them, the domination of men over women was a product of the division of society into classes. The Women’s Union organised meetings to train nurses, but also made numerous demands for women’s rights, such as the right to work, to join a union, and for equal pay (particularly against the anarchist supporters of Proudhon, who said: “Women can only be housewives or courtesans”), and for the closure of brothels.

And there were other women’s organisations during the Commune: Louise Michel’s famous “Club de la Révolution” or the Women’s Committee of the Rue Arras, founded in September 1870, which also played an important role. Its members were responsible for offering various services (caring for the wounded, handiwork, etc.), but also for disseminating revolutionary propaganda and setting up workshops for women. They frequently held conferences, during which their ideas were very well received.

The Commune wanted to extend universal suffrage to women (more than sixty years before the bourgeoisie finally granted it) but it was crushed before it could hold any new elections.

Weaknesses in the face of counter-revolution

The Commune had not organised its defence army in a centralised way to face up to a Versailles army that was being reassembled. It lost time making decisions such as the destruction of the column to Napoleon in Place Vendôme (which took two nights of debate) or arguing with conciliators, such as Jourde, who did not want to nationalise the Bank of France. But, limiting itself to managing the bank rather than nationalising it, meant depriving the Commune of vast resources.

Confined to Paris, the Commune, despite many activities and proposals (most notably of Marx’s followers), did not try to put in place a national revolutionary programme for the whole of the working class and the peasantry. There had been no agrarian reform (collectivisation or sharing out the land), while the highly impoverished peasantry was agitating in the countryside. Despite the efforts of some, including Marx’s followers, extending the Commune outwards did not succeed: Paris was too far ahead of the countryside. The politics of some anarchists did not help matters. Bakunin, who had taken refuge in Switzerland, arrived in Lyon and seized the town hall. Without any analysis of the situation, he single-handedly proclaimed the “abolition of the state” and then put himself at the head of an unelected government. His authoritarianism and the reaction of the troops of the bourgeois state – which had not allowed itself to be abolished simply by proclamation – put an end to the adventure. Bakunin fled to Italy without any further resistance. In Paris, the Thiers government now has its hands free: it has signed its surrender to Prussia on the 10th of May, getting back several thousand captured soldiers.

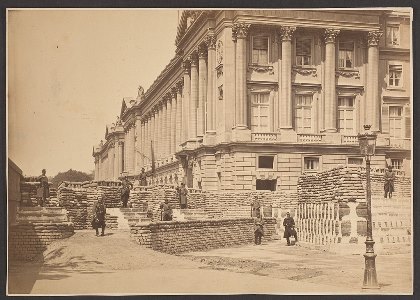

The week of blood

The troops of the Commune were very heterogeneous and some of them not very disciplined. In Versailles, Thiers had an army of 120,000 men which, on 21 May, was to be launched on Paris. The aim was not only to defeat the revolution, but also to carry out a complete massacre. This was especially the case as the communards – “attempting to storm heaven” as Marx wrote – were fighting to the end against capitalist hell. Barricades were to hold out day and night, most notably in the East of Paris. At Place Blanche, the barricade of the Women’s Union, with Nathalie Le Mel and her supporters, defended itself to the end. The communards were being slaughtered in the streets, often on their knees. At the Père Lachaise cemetery, 147 of them were shot in front of the wall of the “Fédérés”. The Belleville district was the last to fall on 28 May.

Between 3,000 and 4,000 Communards died in battle and 15,000 to 20,000 were executed, including children. The barbarity of bourgeois society can be gauged by this torrent of blood.

The Paris Commune was most certainly a devastating defeat for the working class, but it was the first proletarian revolution. For 72 days it established a democratic and egalitarian society. Its strengths and achievements, its mistakes and its weaknesses – such as the absence of a real organised political leadership – will serve as an example for the future, and must be an inspiration to us.

Rich lessons

The Paris Commune is as much a source of inspiration as of understanding. The Commune brought out an important point about the political form of what Marx called, in 1848, the “dictatorship of the proletariat”. That is to say, a dictatorship where the working class – the majority of the population – is democratically organised as the ruling class and organises society to provide for the needs of the whole population. This is totally the opposite of capitalism, where the regime is that of a dictatorship by the bourgeoisie – a class that is in a minority in society, but which makes it function solely for its own interests – profits.

The Paris Commune carried within it elements of a democratic workers’ state – abolition of the standing army and its replacement by the people in arms in an organised manner; elected representatives who could be recalled and held accountable because they were acting in the name of, and in the interests of, the majority.

But the armed communards failed to go after Thiers’ army, which fled to Versailles when his forces were in disarray. Extending the revolution was not a priority for part of the Commune government. Yet, by capturing power only locally, it left the bourgeois state, which was not destroyed, free to prepare the counter-revolution.

This experience confirms the necessity for spreading revolution throughout the country (and later internationally) and the need for a transitional workers’ state to consolidate workers’ power.

All these lessons were understood by the Bolsheviks who, during the Russian revolution of 1917, sent activists into the army to carry out revolutionary agitation work, and often said, “We, we will nationalise the Bank of France”!

The Commune confirmed the extraordinary capacity of the masses to break their chains, and to defend a policy that aims at the emancipation of all humanity. Without such energy and heroism, no change of society, no revolution is possible.

Building a revolutionary leadership

But energy is not enough. The Paris Commune failed because, without a real revolutionary party capable of pushing for the right decisions, indecision prevailed and time was lost. The class enemy could, in its turn, strike and crush the revolution. This is the main lesson for today.

“The workers’ party – the real one – is not a machine for parliamentary manoeuvres; it is the accumulated and organised experience of the proletariat. It is only with the aid of the party, which rests upon the whole history of its past, which foresees theoretically the paths of development, all its stages, and which extracts from them the necessary formula of action, that the proletariat frees itself from the need of always recommencing its history: its hesitations, its lack of decision, its mistakes. The proletariat of Paris did not have such a party.”

“The workers’ party – the real one – is not a machine for parliamentary manoeuvres; it is the accumulated and organised experience of the proletariat. It is only with the aid of the party, which rests upon the whole history of its past, which foresees theoretically the paths of development, all its stages, and which extracts from them the necessary formula of action, that the proletariat frees itself from the need of always recommencing its history: its hesitations, its lack of decision, its mistakes. The proletariat of Paris did not have such a party.” (Trotsky, ‘Lessons of the Paris Commune’, 1921)

Even today, these lessons are vital for those who are serious about preparing the socialist revolution, for it to be victorious and finally rid us of the barbarism of capitalism.