To most socialists, it will come as no surprise to find that Christmas is the continuation of very ancient traditions of mid-winter festivals. However, it may be a surprise to learn just how relatively new our Christmas is. In fact, there are serious arguments to say that this year marks only the two hundredth anniversary of Christmas and not the two-thousandth or so.

Pre-Christian winter festivals

Most civilisations that have existed in the Northern hemisphere have had a mid-winter festival in some form. While the festivals are a human invention, the winter solstice is not. The solstice is determined by the physical nature of our planet. So the first or the taproot of Christmas lies in the very material reality of life in the Northern hemisphere. These winter festivals have generally been associated with feasting.

By the time of the Roman empire, the winter solstice festival was Saturnalia which celebrated the death and rebirth of the sun. It was a carnival of drink, merrymaking, and the exchange of gifts. The Roman civilisation was based on slave labour as the primary means of production. Therefore, the big slaveholders constituted the ruling class.

However another aspect of Saturnalia was a role reversal, where the masters served slaves at the table, and a period of liberty of speech and actions (lawlessness) was the rule. In this respect, it acted as a steam valve releasing the pressures within society. This ‘role reversal’ persisted to a lesser extent in the English tradition of Wassailing and the ‘Lord of Misrule’ throughout the Middle Ages. This theoretical liberty or license was always limited, not least by self-censorship born of an understanding that after the holiday the master was again the master.

The Roman empire regularly integrated the leaderships of conquered peoples into their own society by seducing them with citizenship and the benefits for the elite of a Roman lifestyle. Alongside this Rome also integrated the religious belief systems of their conquered subjects into their own.

By the year 274 of the common era (CE) Gregorian calendar – the numerical equivalent of the anno domini (AD) notation also used – the Saturnalia festival had morphed into the officially recognised celebration of Mithras Sol Invictus (the undefeated sun). Many aspects of the legend of Mithras may be familiar: born on December 25 of a virgin. Born in a cave. The birth was witnessed by shepherds and magi. Raised the dead and healed the sick. Had twelve disciples representing the signs of the zodiac. Held a last supper with his disciples before returning to heaven at the northern spring equinox. Worship included common meals at which bread and wine were served to celebrants. One of the limitations on the spread of the cult of Mithras was that it was male-only.

Christianity

Meanwhile, the new religion of Christianity was gaining adherents within the Roman empire. It began as one of a number of revolutionary movements against the Roman occupation of Judea. Its initial attraction lay in its appeal to the poor, suffering and oppressed of Judea who were looking for a Messiah, a new King David, a war leader to liberate them from Rome and its local clients.

The Christian congregation was imbued with the concepts of mutual assistance, with communal meals and common funds. But with its spread beyond the borders of Judea, there was a switch from liberation in this world to liberation in the next, the promise of heaven.

However, with its promise of a life after death, over the succeeding centuries, it attracted a following amongst other sections of Roman society, including in the army and sections of the elite. The change in membership of the church brought a corresponding change in its nature. Less emphasis was given to the social, communal aspects of the early congregation and more to the apparatus of the church.

It took over three hundred years for the early Christians to feel the need to venerate the birth of Jesus. In fact, throughout the early period, for Christians birthdays were, even if known, generally ignored. What was regarded as important was the date of death and in particular the date of martyrdom (saints days).

In 306CE Constantine was declared emperor by his army legions at York. However, he was only one of seven contenders for the position and only became the sole emperor in 324. The eighteen years between consisted of almost continual civil war between the contenders with shifting alliances, until Constantine was the last man standing.

In 313CE Constantine for the Western empire and another contender, Licinius for the Eastern empire jointly proclaimed the Edict of Milan. It was this proclamation that granted religious toleration for Christians within the empire. In the West, Constantine issued laws to rights, privileges, and immunities from civic burdens on the Christian church. In 321CE he granted the church the right of a legal entity, to own property. What previously had been the common property of the congregation became the property of the church.

For both contenders what was at stake was the support of the legions of the army, particularly those composed entirely of Christians. The final battle in 324CE was between the armies of Constantine and Licinius. According to legend, at this battle Constantine instructed his troops to paint a Christian symbol on their shields. Recognition was given to Christianity as the official religion of the empire. As the Roman philosopher Seneca (4–65 CE) earlier observed, “religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by rulers as useful”.

The following year (325CE), Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea. The outcome of the council was one church, one theology and one bible, acceptable to the emperor. It determined which books would make it into the bible, with more being left out than made it in. Everything outside the official line was to be suppressed with extreme force.

Politically, whether intentionally or not, it was very useful for Constantine, at the end of a civil war, to declare that there was only one divinity, one church, one empire, and one emperor. And an emperor, moreover, apparently chosen by God – as proven in combat – receiving as it were the mandate of heaven.

Constantine died in 337CE. In the same year Julius I became Pope. It was Julius who declared December 25 as the Feast of the Nativity. Probably the date was selected because traditionally within the Roman empire it was already a day of celebration and feasting. The fusion of the Christian and Mithras myths was all but complete.

So Christmas on the 25 December was the lasting outcome of eighteen years of Roman civil war.

The fall of Rome and the rise of feudalism

A first sight it may appear that the fall of Rome was due to invasion by the so-called barbarian tribes along its border. This however was only the final death blow to an empire weakened to the point of collapse by internal decay.

Marxist theory shows that all class-based societies contain within them the ‘seeds of their own destruction’. The Roman slave-based economy required constant warfare and conquest to replenish the slave population. Also, slave-based production is notoriously inefficient. Slaves have no stake in the success or failure of an enterprise. War, division (into the Eastern and Western empires) and economic stagnation weakened the Western empire. It appeared to be a prize there for the taking, unable to defend itself.

The fall of Rome created the conditions for a new step forward. The Barbarian tribes brought with them their own belief systems and traditions, many pre-dating Christianity by thousands of years. According to the Germanic Norse mythology of Northern Europe, Woden or Odin, wrapped in his furs against the winter cold, was not above delivering gifts in winter. It was also from these Northern European cultures that the evergreen trees and plants were brought into dwellings as a symbol of rebirth.

The one part of the Western Roman Empire to survive and claw its way back into prominence was the Roman Catholic church. The church once again quickly adapted to the new reality and the new ruling class. It facilitated the conversion of tribal leaders elected or acclaimed by the whole tribe into kings and lords appointed by God, in other words by birth.

Slavery was replaced as the basis of the means of production by land. Kings held land by the will of God (and the church). The lords held land by the will of the king. The serfs, the lowest order, were tied to the land itself and were passed from one lord to another as part of land transfers. The exploitation of the serfs by the aristocracy was very obvious and took the form of labour dues. Serfs had to provide so many days of labour on their lord’s land and the rest on their own holding. Production was predominately for consumption, whether by the serfs or the lords. Only surpluses were taken to market for exchange. One of the main forms of class struggle used by the serfs to escape exploitation was to run away to the growing towns and cities.

One of the church’s initial use for the new regimes was as a source of knowledge and technique, particularly in agriculture. The great abbeys and monasteries throughout Europe became centres of excellence and trading centres, around which new towns and cities took root.

In the middle ages, the Roman Catholic church was the one unifying political system overarching the various feuding dynasties of Western Europe. It gave kings and lords legitimacy but demanded in return obedience. Disobedience could result in ex-communication, which could be a death sentence. In fact, the church itself was the biggest single feudal landlord, holding a third of the landmass.

Rise of the bourgeois and the language of struggle

Until the French revolution of 1789, all popular risings, peasant revolts and revolutionary movements in the Christian West took place surrounded by the banner of religion. This shouldn’t be surprising to Marxists, as the dominant philosophy of any age is the philosophy or world view of its ruling class. The first signs of a challenge to this rule come not necessarily as a challenge to its economic interests but as a challenge to its philosophy.

For the feudal aristocracy of Europe, their world view and their place in it was intertwined with the Christian religion as expounded by the Roman Catholic church. So, the first action in the revolutionary challenge to feudalism was an attack on the philosophy of the Roman Catholic church, subjecting it to criticism and displaying its hypocrisies. This was combined with a harkening back to an earlier simpler golden age, generally resting on the communal ideas and traditions of the early congregation.

The mediaeval church was the wealthiest single entity in Europe. Wealth poured in from its land holdings (rents and sales of surpluses), market fees, tourism (pilgrimages) and tithes (membership dues). The church land in many cases came from donations or bequests from wealthy families buying their place in heaven.

On a smaller scale, the church sold indulgences or pardons from sins. Gone was the biblical faith that it would be “easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven”. Little wonder that the church and the ruling class opposed, under the threat of death, the translation of the bible from Latin into the everyday languages of the people.

These protesters or protestants represented the growing class of merchants, artisans and financiers who were becoming cash wealthy in the cities by trading goods and services. The aristocracy, in order to obtain these items, including the exotic spices and textiles of the east, required cash. Increasingly this need for cash forced a change from a land-holding model based on the ‘labour dues’ of the serf, to ‘rental dues’ owed by peasants.

For the embryonic capitalist class, the limitations of feudal society were becoming an intolerable burden. Especially when some of the merchants were becoming as wealthy, if not more so, as some of the aristocrats. They created their new philosophy with the idea of a personal direct relationship to God, cutting out the church. This included the idea that God’s will was for each person to strive to better themselves.

The religious struggle was a reflection therefore of the class struggle between the old ruling class of the aristocrats, backed by the Roman Catholic church and the up and coming revolutionary class, the merchants, artisans and so on, the embryo of the capitalist class.

As Friedrich Engels said, “the religious disguise is only a flag and a mask for attacks on an economic order which is becoming antiquated” (On the Early History of Christianity, 1894-95). However, for the participants, these masks could be very real; they were not necessarily conscious, nor needed to be, of the underlying economic forces shaping their thinking and actions.

As part of this ideological struggle, the character we now know as Santa Claus was to play a number of roles.

The Santa Wars

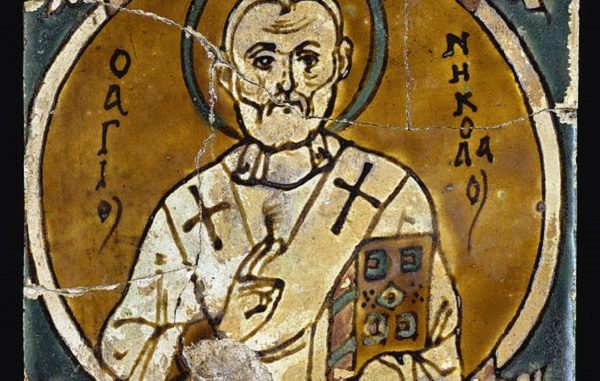

The Santa Claus myth initially comes from Saint Nicholas. Santa Claus is an anglicised distortion of his name in either Dutch (Sinterklaas) or German (Santa Klaus). Nicholas was a Greek bishop in Myra, Turkey, who died on December 6, 343CE. Legend has it that he was one of the participants in the Council of Nicaea and supported the emperor Constantine’s position.

During the Middle Ages, Saint Nicholas was very much the poster boy of the Catholic church. He was celebrated as the patron saint of children (amongst others) and for his generosity. Gifts were said to be delivered by him to children in December. However, these gifts arrived on the eve of his saints day (the day of his death), in other words, the fifth or sixth of December but definitely not Christmas.

In 1517, Martin Luther of Germany was the leading figure of Protestant faith, amongst the first to dispute the ideology of the Roman Catholic church and denounce its excesses. He was very much the representative of the rising merchant class but also was supported by some German princes, who themselves were looking to shake off the restrictions and obligations of the church.

Luther also denounced the concept of saints, and praying to saints as intermediaries ‘between Man (sic) and God’. Therefore, he abhorred the veneration of Saint Nicholas. However, he could not rise above the limitations imposed by the dominant worldview of his time. He, therefore, introduced a contender to Saint Nicholas. In keeping with his new ideology, he claimed the deliverer of presents was the Christ child himself (Christkind, in the German language) corrupted to Kris Kringle.

Luther’s ideas gained ground amongst the downtrodden German peasantry who in 1524 rose up in revolt. Luther, along with the merchant class and the princes, took fright at this intrusion into their intellectual debate with the church as a threat to their own wealth. The peasants’ rising – the Peasants War of 1524-1525 – was bloodily crushed with the full support of Luther and his allies.

In England, for numerous reasons of his own, Henry VIII put himself at the head of the Protestant Reformation. What role lust, desire for a dynastic heir, or financial gain played in Henry’s decision is secondary. That is not to say Henry’s own thinking had no effect on the course of events – it did – but it did not create the underlying conditions.

Henry rested on the Protestants to break with the Roman Catholic church in 1534, with the Act of Supremacy. He declared himself head of the English church subject only to God, an absolute monarch. Once he had broken from Rome, he then moved to take the assets of Rome in England for himself. The dissolution of the monasteries, a series of confiscatory measures carried out between 1536 and 1541, provided Henry with resources and with land to reward his supporters and consolidate his position.

Like Luther, Henry, in the political battle with the Catholic church, fought on the grounds of ideology. The celebration of Saint Nicholas was banned in England and was replaced by a secular personification of the season, Father Christmas. Henry’s Father Christmas had very strong pagan roots in the characters of the Saxon Lord Frost and the Viking Odin. Again, presents were not given out at Christmas but at New Year.

However, the English Protestant reformation movement was not a homogeneous one and was comprised of different wings. On one hand, there was the English Catholic wing that supported Henry rather than the Pope as the head of the English church but otherwise with no change. On the other hand, there were the followers of the French Protestant, John Calvin, who took a far more radical approach.

In England for most of the next century Protestantism was in the ascendancy. After the first-ever victory of a bourgeois revolution in the form of the English civil war from 1642-1648, everything changed. A republican ‘Commonwealth of England’ was created, which by 1653 – and now the ‘Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland’ – was under the rule of the Puritan Oliver Cromwell as the Lord Protector.

The Puritans followed the lead of Calvin, preaching extreme morality. The new orthodoxy was joyless, with most forms of entertainment banned, including Christmas. They proclaimed that one of God’s commands was to ‘labour industriously’. While on one hand, they shunned luxury and promoted thriftiness, on the other hand, they implied God’s favour was displayed by financial success. The new victorious capitalist class had defined its ideology.

Although the republic was overturned and the monarchy restored, there was no return to the absolute monarchy of the Tudor and pre-civil war Stuart period. The rule of feudalism was decisively broken and the rule of the new bourgeois capitalist class had begun. However, Christmas and entertainment were restored.

The New Santa of the bourgeoisie

In order to avoid religious persecution, prior to the civil war, in 1620 a group of Puritans set sail from Plymouth to the New World of America. These Pilgrim Fathers took the austere, festival-free view of Christianity to America with them on the Mayflower.

The idea of Christmas having no religious significance was initially very popular with industrialists in America. It allowed them the perfect excuse to not give workers a day off. In fact, after the victory of the American revolution, the new Congress met on Christmas day.

However, Christmas was smuggled into the USA in the baggage of, in particular, German colonists to Pennsylvania. The Christmas tradition they brought was the German tradition of Kris Kringle, not Saint Nicholas.

By 1800, a New York Christmas day was more like the days of the Roman Saturnalia or the ‘Lords of Misrule’ of the Middle Ages. Drunkenness was combined with physical attacks on bourgeois property and wealthy persons. So much so that the New York Christmas riots of 1828 are given the credit for sparking the creation of the New York Police Department, the NYPD. However, the early 1800s saw a general trend in capitalist countries of the creation of police forces. The bourgeoisie everywhere looked to bolster their state machine, with a new specialised force, to protect them and their property from the enemy within.

While the capitalist class moved consciously to supplement their power with the creation of the new police forces, a complimentary process, whether conscious or not, to supplement their ‘soft power’ was underway, with the purpose of reinventing and taming Christmas.

In 1821, an American book, The Children’s Friend, was published. Arguably, it is the poem, ‘Old Santeclaus with Much Delight’, included in this book, that marks the birth of the Santa and Christmas we know today. For the first time in print, presents are delivered by Santa dressed in a red fur coat, on the night of Christmas Eve. This destroys the myth that the red-coated Santa was a Coca Cola invention for their 1931 campaign. Also, this Santa arrives from the North, in a sleigh drawn by reindeer.

The character of this new Santa was reinforced by the publication of the poem, ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas’, in 1823, where Saint Nicholas enters houses via the chimney. His sleigh is drawn by the now traditionally named reindeer (pre-Rudolf, of course). And his looks owe more to Odin than to the Saint Nicholas of the Middle Ages, in his bishop’s robes.

The integration of the three very distinctive characters of the Reformation period into one character was only completed by getting the stamp of Holywood approval, with the release of the 1947 film, A Miracle on 34th Street. However, the creators of this Santa are reflecting the pressure of the post-war radicalised working class. Santa, who gives his name as Kris Kringle, is arrested for giving presents away on the basis of need, rather than selling them – a most heinous anti-capitalist crime. He is only released by a piece of legal verbal trickery, accepted by the judge but only under the pressure of a mass movement in the streets outside the court.

The history of Santa Claus, as well as Christmas, has been formed in the process of the development of society and the struggle between classes. So what we now know as Christmas is a relatively modern affair of about 200 years old. It is a mixture of both ancient and modern traditions adapted through the ages to meet the needs of the ruling class of the time, be it Roman aristocrats, feudal lords or modern capitalists.

However, its roots go back into the dawn of the human experience of winter in the Northern hemisphere. People gather around the fire to keep warm and feasting to raise their spirits in the cold and dark; and looking forward to the return of the sun and the spring.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||