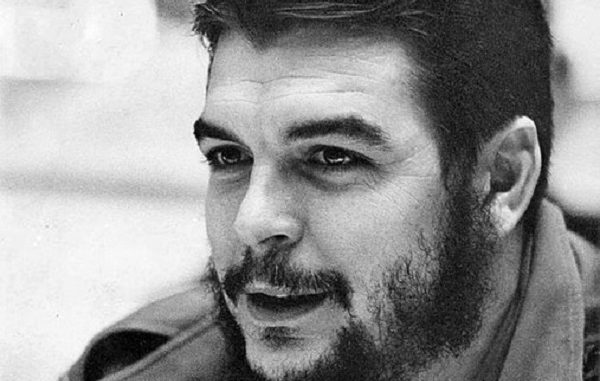

This weekend marks the 55th anniversary of the capture and subsequent assassination of Ernesto Che Guevara in Bolivia, writes Tony Saunois. Today, the image of Che Guevara is familiar to most people. A fashion statement for some, for many others it is a political declaration; they identify with the legacy left by Che Guevara as a symbol of struggle, defiance, internationalism, and a better, socialist world.

“Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man”. These, according to some accounts, were the last words of defiance uttered by Che Guevara before his execution on 9 October 1967 in Bolivia. He was 39.

If Felix Rodríguez, a CIA adviser with the Bolivian army who carried out his execution, thought that by killing Che he would also bury his appeal and inspiration he could not have been more wrong.

On the anniversary of his execution it is apt to salute his struggle against oppression, and also to draw lessons from his experiences, positive features, and mistakes. These are important for the battles of the working class in Latin America and internationally.

As an Argentinean medical student, Che Guevara undoubtedly could have secured a comfortable life. Yet, like the best of the left-wing radical middle class, he turned his back on such comforts and committed his life to fight capitalism.

He was drawn into political struggle, mainly as a consequence of the poverty and the struggles he witnessed during his two famous odysseys in 1952 and 1953-4, depicted in the book and film, The Motorcycle Diaries.

As well as his encounters with socialists in Peru, communist copper miners in Chile, the magnificent Bolivian revolution and a host of others, he was deeply affected by his visit to Guatemala. Here he witnessed the struggles under the radical left-leaning populist government of Jacobo Arbenz.

By attempting to introduce some relatively limited reforms without breaking from capitalism, Arbenz was trapped, giving the counter-revolution time to plot and organise, which they did. Arbenz failed to act and put his faith in the “democratic constitutional loyalty” of the armed forces and refused to arm the masses.

This government was eventually overthrown by a CIA-backed coup.

Based on his experiences in Guatemala and discussions about Cuba, Che was repelled by the Communist parties, whose approach he found too ‘conservative’ and ‘orthodox’.

In fact, they did not have the objective of fighting for socialism but of firstly strengthening ‘parliamentary democracy’, developing a national industry and economy, and passing through a stage of capitalist development before it was possible to move towards the working class taking power.

As a result in many countries, the workers’ movement was effectively paralysed and disarmed. Che rejected this approach, although he had not developed a rounded-out alternative. He was drawn towards the struggle unfolding against the Batista regime in Cuba and joined the ’26 July Movement’ in Mexico.

The 26 July Movement (named after the doomed attack on the Moncada barracks in 1953 led by Fidel Castro) was at that stage quite a wide-ranging organisation. It included a liberal democratic wing but Che emerged as a prominent representative of the movement’s more radical elements.

It was on 2 December 1956 that a small, badly organised group of 82 guerrilla fighters, including Che Guevara and Castro, landed in Cuba and began what became a two-year guerrilla war. Culminating in the downfall of the hated Batista dictatorship, it led to the Cuban revolution.

Che’s heroic role was made all the more so by his life-long struggle with asthma. Every obstacle, hardship and pain necessary to endure fighting a guerrilla war was exacerbated by his condition. Revolutionary determination precluded letting his health prevent him from playing a decisive role in the struggle.

Ebbing and flowing, the war progressed and the guerrillas won increasing sympathy from the peasants. In the cities the anger and hatred against the Batista regime also approached boiling point. As the regime collapsed, the rebels entered the cities on New Year’s Day 1959 and were greeted by the eruption of a massive general strike.

But the process that unfolded meant that the working class in the cities played an auxiliary role to the guerrilla war. The absence of a conscious, organised movement of the working class in the leadership of the revolution had consequences.

In the early stages of the revolution, when Castro and Che Guevara entered Havana, it was not yet fully clear how far events would go. While Che was a committed socialist, at this stage Castro was limiting himself to a more ‘liberal’ and ‘humane’ capitalism.

Capitalism overthrown

From 1959 the revolution in Cuba was driven forward, following a series of tit-for-tat blows with the USA, until three years later, capitalism and landlordism were eventually overthrown.

This process was possible at that time because of a combination of factors, especially the massive pressure from the workers and peasants. US imperialism refused to even attempt to embrace and influence the regime and instead imposed a boycott that has lasted until today.

Another crucial factor was the existence, at that time, of centralised planned economies in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Although these were ruled by vicious, bureaucratic dictatorships they appeared to offer an alternative to capitalism.

These factors meant a nationalised centrally planned economy was eventually introduced. Such a tremendously positive step forward had an electrifying effect across the world. Che Guevara played a crucial role in this process.

From the outset, he was pushing for the revolution to take a more ‘socialist’ road and stressing the need for it to be spread internationally. He played an important role in drafting what was known as the Second Declaration of Havana which makes inspirational reading even today.

Among other things it answers the question of why the US responded with such ferocity to the revolution on a relatively small island: “[The USA and ruling classes] fear that the workers, peasants, students, intellectuals and progressive sectors of the middle strata will, by revolutionary means, take power… fear that the plundered people of the continent will seize the arms from their oppressors and, like Cuba, declare themselves free people of America”.

Che undoubtedly aspired to the idea of the international socialist revolution, but his greatest weakness and the greatest tragedy was his lack of understanding of how this was to be achieved. He had been drawn towards the guerrilla struggle as a means of winning the socialist revolution. At that stage, he had not yet understood the crucial role the working class must play in transforming society.

Even in countries where the working class in the cities comprised a minority of the population its collective role and the consciousness, which arises from its social conditions in the factories and workplaces, means that it is the decisive class for spearheading and leading the socialist revolution. This was the experience of the Russian revolution in 1917.

In practice, the capitalist classes in neo-colonial countries are tied to both landlordism and imperialism. On this basis, they have demonstrated that they are incapable of developing the economy or industry, building a stable democracy, or of resolving the national question. These tasks were solved by the democratic bourgeois revolution in advanced capitalist countries, such as Britain or France.

However in the modern epoch, in the neo-colonial world, these tasks cannot be resolved by the weak capitalist classes. Fulfilling them is linked, as Trotsky pointed out in his theory of permanent revolution, to the socialist transformation of society on an international scale.

Because of the rottenness of the Batista regime and the political vacuum in Cuba, it appeared that guerrilla struggle offered the way forward. In reality, even there it had come together with the eruption of a general strike after the war was effectively won as the guerrillas moved into Santa Clara, Havana, and other cities.

Based on his experience in Cuba, Che wrongly attempted to replicate this, first in Africa and then in Latin America. Conditions were entirely different and the working class was in a much stronger position with more revolutionary traditions and experience. The lack of a rounded-out, conscious understanding of the role of the working class in the socialist revolution was undoubtedly Che Guevara’s biggest political weakness.

Gains

Even today, ravaged by both the loss of economic subsidies, as a consequence of the collapse of the former Soviet Union, and the effects of the US-imposed boycott, the gains of the Cuban revolution are to be found in the form of one of the best health systems in the world, free to all. Within years illiteracy was abolished. One teacher per 57 inhabitants makes the teacher-pupil ratio one of the best in the world. The same can be said of doctors.

None of these gains would have been possible without Cuba’s planned economy and the revolution. The Committee for a Workers’ International supports all the gains of the Cuban revolution yet, at the same time, the initial form the revolution took had consequences for the nature of the regime that was established.

The government led by Castro and Che after the revolution enjoyed overwhelming support. However, the absence of the organised working class consciously leading the revolutionary process meant that a genuine workers’ and peasants’ democracy was not established.

Although elements of workers’ control existed in the factories there was not a genuine system of democratic workers’ control and management. Consequently, a bureaucratic, top-down regime developed.

Che was instinctively against any privileges being taken by any government official or representative. In Cuba, he was very harsh with those in his department who attempted to take even the most minimal perk.

Travelling to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, he was repelled by the lavish lifestyles of the bureaucrats and the contemptuous attitude they adopted toward the working class. Bureaucratic features present in Cuba increasingly frustrated him.

Searching for an alternative

Despite reacting against the horrific, monstrous bureaucratic dictatorship in Russia and Eastern Europe, which, on one occasion he described as “horse-shit”, he did not develop a clearly formulated alternative to it or see how to fight it. But he was undoubtedly searching for such an alternative. He was later denounced as a Trotskyist by the Soviet bureaucracy.

According to some reports Che was carrying Revolution Betrayed by Trotsky in his knapsack in Bolivia. In fact, he had earlier been introduced to some of Trotsky’s writings. The Peruvian former air force officer, Ricardo Napurí, who had refused to bomb a left-wing uprising in 1948, gave Che Guevara a copy of Permanent Revolution when he met him in Havana in 1959.

A willingness to discuss and explore different ideas and opinions was a feature of Che’s character. Unfortunately, despite reading some of Trotsky’s writings by the time of his premature death, Che had not drawn all the necessary conclusions to develop a coherent and rounded-out alternative.

To do so required a massive leap in understanding. His isolation, without the contact, discussion, and exchange of ideas that are part and parcel of membership of a party, along with the absence of a broader international revolutionary experience to draw on, made such a leap extremely difficult.

Had Che lived and experienced more international struggles of the working class, and further debate, he would probably have drawn the right conclusions.

The deficiencies in Che’s understanding had tragic consequences for his own life and in the flawed model of guerrilla struggle. Yet, his positive features and lasting legacy as a symbol of uncompromising, self-sacrificing, incorruptible struggle, serve as a source of inspiration today. If the lessons of his mistakes can also be learned, then his determined struggle for an international socialist revolution will be achieved.