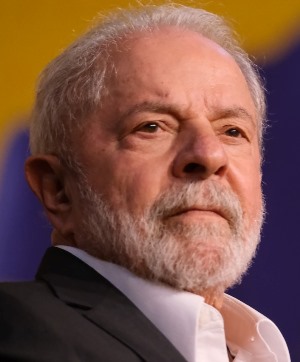

In the tightest presidential election ever in Brazil, the far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro was narrowly defeated by the veteran candidate of the Workers’ Party (PT), Luiz Inácio da Silva, popularly known as Lula. Lula scraped to victory taking 50.9% of the vote to Bolsonaro’s 49.1%. Lula won 59 million votes to Bolsonaro’s 57 million. Brazil is now a highly polarised and divided society. Despite Lula’s victory, the battle for Brazil is not over.

The defeat of Bolsonaro was celebrated by millions who feared a second term for the far-right reactionary populist. The narrowness of the result has shocked many given the catastrophic consequences of his government. A Covid-denier, Bolsonaro presided over 900,000 deaths during the pandemic. Millions have been driven into poverty and living standards have fallen. Vicious racism, homophobia, and misogyny have been the hallmark of his regime, along with the destruction of vast swathes of the Amazon rainforest as he colluded with loggers and powerful landowners.

At the same time, his populism managed to win support among the large Brazilian middle class and sections of the urban poor, featuring the fears of many, of violence and crime. Bolsonaro also introduced a social welfare system, Auxillio Brasil, which offered payments to some of the poorest, including a payment of US$120 between October 11-25 and the distribution of gas vouchers. This was combined with an appeal to reactionary sections of society, under the slogan of “family, patriotism, and religion”. He made this appeal to those layers that have been drawn to the evangelical churches which have grown massively in recent decades, and according to some estimates now embrace up to one-third of the population.

Millions rallied to support Lula in order to eject Bolsonaro. However, many did so with a heavy skepticism because of the record of past PT governments. Lula was president for two terms, and first elected in 2003. Under his presidency, he was able to introduce social reforms, which opened the universities to millions from the ‘favelas’, especially black youth who had previously been excluded.

Welfare programme

An extensive social welfare programme, Bolsa Familia, provided financial aid to some of the poorest. When Lula left office after his second term, he enjoyed an 80% approval rating. These reforms were also accompanied by privatisations and attacks on the pension system, which led to a left-wing split from the PT and the formation of the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL). The reforms introduced were possible at that time because of a boom in commodity prices, and the explosion of exports to the then-growing Chinese economy.

However, his appointed successor, Dilma Rousseff, also from the PT, who was elected in 2014, faced an entirely different economic and world situation and a recession in Brazil. Living standards fell and unemployment rose. At the same time, the PT was embroiled in an explosion of corruption scandals involving huge sums of money. An investigation into corruption, called Lavo Jato, led by a right-wing judge, implicated Lula who, for a period, was imprisoned for corruption. He was later released and cleared of all charges. However, the PT was riddled with corruption. The stench of corruption still remains, haunting the PT and other parties and politicians. This was exploited, to the full, by Bolsonaro and his supporters during the election campaign despite their own corrupt practices.

The failure of the ‘left’ PT to break with capitalism when in government ultimately sowed the seeds allowing Bolsonaro to build a powerful right-wing reactionary bloc. They also exploited, to the full, the catastrophic situation in Venezuela, warning that under Lula, ‘socialism’ à la Venezuela would result. The failure to break with capitalism, combined with the US embargo and top-down bureaucratic, corrupt methods under Hugo Chavez, and more so under Nicolas Maduro, and the economic and social disaster which has followed, have given a weapon to the right-wing throughout Latin America to attack the left and socialism.

At the same time, in Brazil, the left split from the PT – PSOL – failed to build a mass alternative with a solid base among the working class and poor throughout the country. In this election, PSOL wrongly failed to stand its own candidate in the first round of the presidential elections and has suffered splits.

Safe pair of hands

Lula has made enormous efforts to prove that he is a safe pair of hands for capitalism. He even formed a coalition with the right-wing Geraldo Alckmin, who stood against Lula in the 2006 election. He was endorsed by former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2003), who implemented neo-liberal policies and faced a massive corruption scandal, all of which triggered a massive movement against his government. Lula succeeded in winning the 2003 election for the first time.

The rapid recognition of Lula’s victory in 2022 by Biden, Macron, Putin, and other international capitalist leaders, shows they do not see his government as a threat to them. His endorsement by capitalist politicians, previous adversaries who he now praises, is not what allowed him to win a narrow majority. Lula’s victory has arisen from the hatred of Bolsonaro by millions who wanted him out. The PT victory is not a consequence of Lula making a compromise with capitalism.

A majority of the main bourgeois interests in Brazil, and internationally, backed Lula against Bolsonaro. They never backed Bolsonaro when he stepped into the political vacuum and won in 2018. At that stage, all of the traditional capitalist parties and the PT suffered a collapse in support and credibility.

In the run-up to the 2022 election, it seemed possible that Bolsonaro would attempt to ‘do a Trump’ and refuse to accept the election result. Bolsonaro had a strong base of support within the military, and had relaxed gun controls, making it easier for his supporters to arm themselves. Should he have mobilised his base and sections of the military, and tried to cling to power through some form of an attempted coup, it could have triggered a social explosion and armed conflict with elements of civil war.

It seems, at the time of writing, the military and other political leaders supporting him have pulled back from such actions for fear of the consequences which would flow from them. Bolsonaro has not been seen since the election and has not yet conceded defeat. Truck owners have taken to the streets to block highways, at the time of writing. It is still not excluded that he may attempt to cling onto power through some form of attempted coup. However, this seems less likely at this stage. Such a step would be very dangerous for capitalism. Should Lula come to power following such a conflict, the masses would become radicalised and would demand the government go further and take more radical measures that could encroach on the interests of capitalism.

This could change should sections of Bolsonaro’s base attempt to mobilise their forces to prevent Lula from taking office in January 2023. The working class and left cannot rely of Bolsonaro not attempting to remain in power, nor on the political leaders of Lula’s pro-capitalist coalition. A mass mobilisation needs to be organised to take any measures necessary to prevent Bolsonaro or his supporters from clinging onto power and staging a coup.

Although Lula won the presidential election, Bolsonaro’s supporters still control São Paulo state. Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas, Bolsonaro’s former infrastructure minister, won the governor’s race in Brazil’s biggest state, São Paulo. In Congress, in the lower house, Bolsonaro’s right-wing bloc is the largest. Lula has a bloc of only about 25%!

The next Lula government will not maintain the support of his first two terms as president. His coalition of the PT and right-wing capitalist parties is unwieldy, and splits are certain to open up. Moreover, Lula is not coming to power under the relatively favorable economic conditions as when he was first elected. Brazil faces its own recession, as well as a global one, inflationary crisis, and higher interest rates. Lula, following his election victory, has declared that he will: “Govern for 215 million Brazilians. Not just those who voted for me. We are one people, one country, one great nation”. Yet Brazil is not one country. It is not “one people”! Brazil is highly polarized, both socially and politically.

Lula declared: “We no longer want to fight. We’re tired of seeing the other as the enemy”. This is not how the Bolsonaro right-wing views the impeding struggles that will develop.

Poverty

Lula has promised to lift 100 million people out of poverty. However, he has announced no programme of how this is to be done. Moreover, facing an economic crisis domestically and internationally will prevent the introduction of sustained and lasting reforms.

Lula’s attempts at reassuring capitalism that he is a safe pair of hands are not satisfying sections of the ruling class. As one banker very consciously put it just before the election: “We will get Lula elected in order to stop Bolsonaro. Then, on day one of his government, we go into opposition.”

Lula is likely to stop or reduce the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, which has been taking place unfettered under Bolsonaro. But his coalition government will not be stable and will go into crisis, as divisions and splits open up. It will not have the prospect of implementing the scale of social welfare programmes that were introduced during Lula’s previous governments.

Following the election, a renewed battle for Brazil will open both with Bolsonaro’s reactionary forces and with the ruling class. The PT is now wedded to capitalism and riddled with corruption. The working class, and all those exploited by capitalism, need to prepare for the struggles that will rapidly unfold. A part of this struggle is to build a mass party of the working class with a democratic socialist programme to break with landlordism and capitalism; to offer a real way forward and defeat Bolsonaro’s reactionary right-wing populism and the capitalist system from which it arose.