As workers involved in the current strike wave in Britain are increasingly supporting calls for a 24-hour general strike, Kevin Parslow looks at the general strike organised by the Chartists in 1842.

In December 1842, the Chartists in Britain, the first mass working-class political party in the world, held a convention at the end of a tumultuous year. The outcome of the convention saw those forces favouring a parliamentary road and conciliation with the existing capitalist parties break with the Chartist movement. Those prepared to fight with and for the working class remained.

Historian Dorothy Thompson suggested that 1842 was a “year in which more energy was hurled against the authorities than in any other of the 19th century”. That year had seen a general strike, possibly the biggest movement of workers in Britain in the nineteenth century. Sometimes called the ‘Great Strike’, half a million workers were involved in action against the attempts of factory employers to reduce their wages. Inspired and organised by the Chartists, they also took up political demands to fight for representation for working-class people.

British capitalism developed at a rapid pace in the first half of the nineteenth century, developing new factories with thousands of workers, but with terrible pay and conditions for those employed in them – men, women and children. This, though, was also giving rise to a potentially powerful working class, capable of fighting independently for its own industrial and political demands.

Workers’ anger and power

Workers had shown their anger and potential power on several occasions before; for example, the demonstration that ended in the Peterloo massacre in 1819 followed the thwarting of strikes in the north-west mills; there was an uprising in Merthyr in 1831, and attempts to coordinate trade unions foundered as the authorities prosecuted and even transported trade unionists like the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Parliament had passed the 1832 Reform Act as a means of incorporating the higher sections of the middle class into the electorate and weaning them away from radical politics. But workers were excluded from the franchise. Demands for political representation, which were seen by workers as a means to an end in the class battles against the bosses, rather than an end in itself, were taken up by the London Working Man’s Association, formed in 1836, and others. The Association called a conference on political representation and the ‘People’s Charter’ was discussed and agreed; its supporters became known as ‘Chartists’.

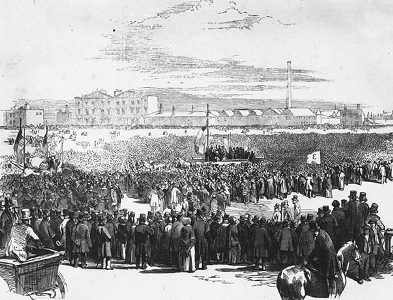

The Chartists agitated for their political demands but also in support of working people’s economic needs as well. This gained it great support among the working class, and mass assemblies were held in towns up and down the country. Stephens, a Methodist minister, said in a meeting of 200,000 men on Kersall Moor, near Manchester: “Chartism, my friends, is no political movement, where the main point is your getting the ballot. Chartism is a knife and fork question: the Charter means a good house, good food and drink, prosperity, and short working hours.”

Newport rising

A petition was set up around the People’s Charter, which was signed by 1.3 million people. Parliament voted to ignore it in July 1839. The following November, a Chartist-led uprising was put down in Newport, Wales. (see Chartism the world’s first working-class movement).

But capitalism was to enter into a depressionary phase. From 1841 there was a downswing in trade and the effects of bad financial investments in the USA and the UK. Factory owners began to make cuts to pay, some by as much as 25%, and lay off workers. The Chartists launched a second petition for political reform, which garnered 3 million signatures, but was rejected again by parliament, in May 1842.

Having been ignored on the parliamentary field, workers began to fight back, demanding that wages be restored to 1840 levels, and that the People’s Charter be adopted. A series of battles broke out, in workplaces and in the towns. The main regions involved were the Midlands, the north-West and Yorkshire in England, and the Strathclyde area of Scotland, but action took place from Dundee to Cornwall.

The first action took place among the Staffordshire miners in July 1842, and this was followed by the ‘Pottery riots’ in the Stoke area in the same month. In Stalybridge, a town in north-east Cheshire, where 10,000 people had signed the Chartist petition, workers fought back against pay cuts in the mills. Their living conditions were no better. Friedrich Engels, in his ‘Condition of the Working Classes in England’, wrote two years later that the town’s “multitudes of courts, back lanes, and remote nooks arise out of [the] confused way of building… Add to this the shocking filth, and the repulsive effect of Stalybridge, in spite of its pretty surroundings, may be readily imagined.”

In Yorkshire and other mill towns, the protests became known as the ‘Plug Plot Riots’, as the boiler plugs in steam engines were removed, and production had to be halted. In Halifax, six people were shot dead by the authorities. Calderdale Trades Council unveiled a plaque to these martyrs this year.

Protests and riots became widespread in the areas affected and brutal tactics were used to suppress the protests. In the Potteries, 116 people were imprisoned. 19-year-old Josiah Heapy was shot in the head and killed. In the north west, around 1,500 protesters were arrested. Four people were shot in Preston.

Hundreds of Chartists were arrested and imprisoned, including leaders Fergus O’Connor, George Julian Harney and Thomas Cooper, and almost the entire Chartist executive. However, only Cooper was found guilty of any ‘offence’, for speaking to strikers in the Potteries.

Under the heel of repression, the strikes began to wind down from the middle of August. Lancashire and Cheshire saw the strikers stay out longest, with Manchester power loom weavers only going back to work on 26 September.

Without a doubt the ruling class, as they had been at Peterloo, in Newport, and in other places, was terrified of the power of the working class being manifested in society. They stopped at nothing to crush the movement and the Chartists. “In Chartism it is the whole working class which arises against the bourgeoisie, and attacks, first of all, the political power, the legislative rampart with which the bourgeoisie has surrounded itself,” wrote Engels, “…the fruit of the uprising was the decisive separation of the proletariat from the bourgeoisie.”

As the 1842 Convention proved, the fair-weather friends of the working class departed the movement, leaving what are sometimes called ‘physical force’ Chartists, in reality those who backed the workers’ movement. There are lessons from this struggle in today’s trade union battles, in the need for an industrial movement to build its own political force in the struggle to change society.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |