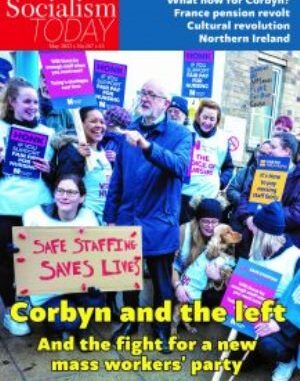

After the British Labour Party national executive committee voted 22-12 to ban its former left-wing leader, Jeremy Corbyn, from standing as a Labour candidate in the next general election, HANNAH SELL looks at the fight for a new mass workers’ party and contrasts the approach of the Socialist Party with others on the left.

The rise and now the dramatic fall of Jeremy Corbyn within the Labour Party opens up qualitatively new terrain. Discussions on how the workers’ movement can have a political voice are set to intensify.

This is not a new debate. It has ebbed and flowed, in different forms, ever since Tony Blair began the process of transforming the Labour Party into ‘New Labour’ over 30 years ago. In 2004 the Fire Brigades Union disaffiliated from Labour, following its national strike against a pay offer overseen by Tony Blair’s New Labour government. Also in 2004 the Rail Maritime and Transport (RMT) workers’ union, whose predecessor union was central to Labour’s foundation, was summarily expelled by the Labour Party executive for the ‘crime’ of some of its branches backing non-Labour socialist candidates.

Nonetheless, despite huge discontent, the majority of trade unions maintained their Labour affiliation throughout the Blair years, and no new mass trade-union-based party came into existence then or afterwards. This is used by some as an argument that the trade unions’ relationship with Labour is immutable and unchangeable. But this is negated by reality. Substantial and rapid shifts have taken place over recent decades, and much greater changes are likely in the coming years. The ground is being prepared for a new political upsurge, which the lessons of the last period could potentially lift onto a higher level than Corbynism.

Today we have a New Labour Mark Two pro-capitalist leadership of the party. Yet, just eight years ago Jeremy Corbyn was thrust into the leadership of Labour by a huge popular anti-austerity surge from below. This in turn was a dramatic change from what came before. In the 1990s Labour had become a completely reliable tool for the capitalist class, different to the ‘capitalist workers’ party’ it had previously been – when it had a leadership at the top which invariably reflected the policy of the capitalist class, but with a socialistic ideological basis to the party and a structure through which workers could move to challenge the leadership and potentially threaten the capitalists’ interests.

Rise of Corbynism

In the years before Corbynism, given the transformation of Labour into an unalloyed capitalist party – still with union affiliation but with unions’ ability to influence the party via its democratic structures destroyed – we argued for steps towards the working class founding a new mass party. In a number of other countries, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, there was the development of, at least, substantial new left parties – including Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece.

However, in Britain, events took an unexpectedly different turn. Corbyn benefited, almost accidentally, from a change in Labour’s constitution which allowed non-members for the first time to become ‘registered supporters’, with the right to vote in leadership elections, for the price of a pint of beer! The intent was to further diminish the influence of the trade unions and to shut out their collective effect. For this reason, the Socialist Party originally opposed the introduction of this measure. However, when hundreds of thousands of young people and workers, completely alienated by the austerity of neoliberal capitalism, seized this weapon to ‘join’ the Labour Party en masse, propelling Corbyn into the leadership, we not only welcomed this but fought at every stage for the opportunity created to be grasped to transform Labour into a mass democratic party of the working class.

That opportunity was not taken. The hundreds of thousands of mainly young people who rallied to Corbyn were not organised into a force to transform the party, and to deselect the pro-capitalists from office, but were instead encouraged to retreat and compromise in the name of unity.

They had a brutal lesson. The Blairite wing of the Labour Party, and behind them the capitalist class, were terrified by Corbyn’s success. They moved might and main to defeat him, and now, in their frenzy to smash the embers of Corbynism into dust, they have gone far further than even during the New Labour era Mark One. A man who was the leader of the Labour Party three years ago is now banned from standing as a Labour candidate by a clear majority vote on Labour’s national executive. The Labour left is marginalised: its votes within Labour back to the level that they were at the height of the Blair era.

One indication of the current balance of forces within the Labour Party was last year’s national executive elections when the four left Momentum-backed candidates received just 22,649 votes. This is the same level that the left had under New Labour Mark One – for example in the 2008 NEC elections their top candidate received 20,203 votes. Compare this to the 313,209 votes that Corbyn won when he was re-elected as Labour leader in 2016, following the so-called ‘chicken coup’. Many of those people have since left Labour in disgust. The membership is now reportedly 377,000, almost 200,000 less than in 2017.

What now?

Nor are events within the Labour Party the only thing that has changed in recent years. We are in the midst of the biggest waves of strikes for over thirty years, compared with record low levels of industrial action in the years before the pandemic. Many of those striking were first politicised by their experiences of Corbynism. While they are currently focused on strike action, their recent experience also poses sharply the need for a mass political party which fights for those demands.

Right now, however, there is seemingly no viable outlet for such an upsurge. Had even one or two trade unions taken the initiative that situation could be transformed in a flash. The hero status of Mick Lynch, general secretary of the RMT, in the early weeks of their strike action last summer gave a glimpse of the power of the workers’ movement to have a political impact. Unfortunately, instead of taking steps towards a new party, he was a key figure in the launch of ‘Enough is Enough’, which looks back towards Labour.

The absence of qualitative steps towards a new mass party will undoubtedly lead some delegates to this year’s affiliated union conferences to keep the status quo, hoping against hope that this will give them some influence, however limited, on an incoming Labour government. While there is widespread anger with Starmer, at the same time most of the new generation of trade union activists cannot remember the miserable reality of New Labour Mark One, and inevitably hope that Mark Two will, at least, be an improvement on the Tories. In reality, given the weakened state of British capitalism today compared to the 1990s, Mark Two will attempt to oversee greater attacks on the working class than took place in the Blair era.

Seeing this, and the huge gulf between Labour under Corbyn and Starmer, there will also be trade unionists arguing to back candidates outside of Labour. Their numbers would be swelled dramatically if Corbyn in the meantime announces that he intends to contest the next general election as an independent or, preferably, under the banner of a new, democratic party initiated with at least a section of the trade union movement. However, Corbyn’s plans may not become clear until after the Islington North constituency Labour Party has gone through the selection process, and probably been suspended for trying to select him as their candidate.

What approach should Marxists take in this period of flux? Unfortunately, with the exception of the Socialist Party, most Marxist groupings have no way forward to offer. Truth is concrete. Any serious organisation which claims to be Marxist has to have an answer to what should be done next on all the central questions facing the working class, including the issue of political representation.

Radical avoidance of the point

The Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP) are a prime example of how to evade this vital question, in the same way as they have during the whole Corbyn era. In response to the Labour national executive decision to ban Corbyn from standing for Labour, they correctly point out that, “the routine call from the Labour left group Momentum – that the important thing to do is to stay and fight in Labour – convinces fewer and fewer activists. They can see, painfully clearly, that staying in means mounting no fight at all”. (Time to leave Labour after Corbyn’s ousting, Socialist Worker, 28 March 2023)

But what is their alternative? They conclude that if Corbyn stands outside of Labour they will support him, “but for us, parliament and elections have never been the most important thing. Strikes, demonstrations and riots such as those happening in Britain, France, Greece and across the world have always been more important. Rather than pinning hopes on the weakness of a few MPs constrained by parliament, they tap the unrestrained power of mass action by working-class people. And now they can give us better hope”.

This sounds very ‘radical’, but it avoids saying anything about the issues actually being posed. Will the SWP support the motions, initiated by Socialist Party members, which will be debated at the Unite rules conference this year, calling for its political fund to be opened up so the union can back candidates outside of Labour that have a programme in Unite members’ interests? Or will they abstain, or even vote against, because having more MPs “constrained by parliament” will hold back the workers’ movement?

What attitude should Marxists take to parliament? The SWP downplays its importance, on the grounds that it is a capitalist institution. The latter is of course correct. It is part of the capitalist state, which ultimately exists to enable the domination of the majority by a tiny capitalist class. Capitalist democracy is very limited, with the chance to vote in a general election every few years, but then with no real right to control or recall those that have been elected. From the moment they enter the hallowed halls of Westminster, MPs are drawn into the ‘old boys’ (and these days a few girls) club, distant from the pressure of the working class. Any who do not become reliable representatives of capitalist interests are marginalised. Jeremy Corbyn’s treatment as leader of the opposition – where he was routinely not given intelligence briefings to which he was entitled, and senior military figures said that they would not answer to him if he became prime minister – gives a glimpse of how the capitalist state would attempt to block any actions of a democratically elected government if they threatened the interests of the capitalist class.

It is absolutely clear that the socialist transformation of society will require not just a government passing laws through parliament but, crucially, the mass of the working class mobilising, organising in its own party, and struggling for a programme to break the levers of power held by the capitalist class; beginning by taking over – under democratic workers’ control and management – the major corporations and banks that dominate the economy. Such a mass movement would also start to lay the basis for a new society developing a far deeper, more thoroughgoing kind of democracy than exists under capitalism. However, these fundamental points do not lead to the conclusion that participating in capitalist parliaments is unimportant. Whatever ‘radical reasons’ are given for it, standing aside from this struggle is a serious mistake.

Even though trust in capitalist institutions has declined over recent decades, the majority still look towards parliament as a means of winning change. There is a sizeable layer who are so angry with all politicians that they boycott the electoral field, but most do not see another way to change things, feeling, on the contrary, powerless. Generally speaking, the more active layers of the working class – not least those currently on the front line of the strike wave – are also the most likely to vote. Abstract phrase-mongering about ‘the streets’, as a justification for “holding aloof from parliaments”, as Vladimir Lenin leader of the Russian revolution put it, does nothing to help “the mass of unenlightened and semi-enlightened workers” draw socialist conclusions. (Collected Works volume 31, 12 June, 1920)

Debates amongst Marxists

The SWP seems to base its misinterpretation of Lenin on the debates on whether to boycott the Russian Duma, the “most reactionary of parliaments”. Pre-revolutionary Russia was governed by a dictatorship, an absolutist monarchy. The Tsarist regime was profoundly shaken by the powerful 1905 revolution, where ‘soviets’ came into existence for the first time. These were democratically elected and accountable committees of workers created during the revolution to organise the struggle, and later, in 1917, were to become the organs through which the new society would be built.

After the crushing of the 1905 revolution, the Tsar was forced to concede the establishment of the Duma; a puppet parliament. Debates then took place on the left about whether to boycott. The SWP like to use a quote from Lenin in 1906, featured by Tony Cliff in the first volume of his biography of Lenin, Building the Party: “We shall not refuse to go into the Second Duma when (or ‘if’) it is convened. We shall not refuse to utilise this arena, but we shall not exaggerate its modest importance; on the contrary, guided by the experience already provided by history, we shall entirely subordinate the struggle we wage in the Duma to another form of struggle, namely strikes, uprisings, etc”.

This was written when the lava from the 1905 revolution was still warm, an event undoubtedly on an infinitely higher level than participating in an election! However, it is linked to the often-quoted idea that Lenin saw elections as a ‘lower’ form of struggle in general. In reality, he explained what he actually meant by this in September 1909, when a period of reaction had set in, where he is again arguing against the case for a boycott of elections put by the supporters of Otzovism (‘recallists’). The latter argued that “at a time of acute and increasing reaction… the party cannot then carry out a big and spectacular election campaign, nor obtain worth-while parliamentary representation”.

Instead, they proposed more seemingly ‘radical’ actions. Lambasting them, Lenin argues that converting the “direct struggle of the masses… into the real beginning of an uprising” is certainly “the highest stage of the movement, and parliamentary activity without the direct action of the masses the lowest form”. But the further the party is from “connection with the masses”, however, “the more immediate becomes the task of utilising the methods of propaganda and agitation created by the old regime”. Given the level of class struggle at that stage, the Otzovists proposals were no more than adventurism and utopian phrase-mongering, whereas via the ‘lower’ level of activity they were rejecting, it would be possible “to prepare the minds of the masses” for struggle.

How do these broad lessons apply today? Clearly riots – unorganised outbursts of anger – are on a much lower level than a list of workers’ candidates for the general election, organised by militant trade unionists, and standing on a socialist programme would be. On the other hand, the current waves of strikes do represent an important step forward in the confidence and cohesion of the working class. The mood to coordinate the strikes shows how they have started to go beyond fighting against one individual employer but also have an important generalised anti-government element. Nonetheless, at this stage, only the first beginnings of rebuilding the workers’ movement have developed. New stewards and reps are being elected in hundreds of workplaces, but being organised together across their union to transform it into a fighting democratic body, never mind coming together across the workers’ movement to coordinate from below, are still mainly tasks for the future.

If the main political conclusion drawn by this new generation of fighters is the need to ‘vote Labour to get rid of the Tories’, which is the position the SWP have put in recent elections and are likely to again, then that will represent a much more limited step ‘forward’ – if it is forward at all – than if at least sections of the trade union movement decide that they want to have their own candidates in the general election, fighting on a programme in the interests of the working class as a whole, rather than being forced to choose between different brands of fundamentally similar capitalist politicians. Instead of decrying the “weakness” of MPs “constrained by parliament” why not fight for the workers’ movement to get its own representatives elected who will use the platform of parliament to fight for their class?

Or remain clinging on to Starmer’s Labour?

Of course, there are also still self-identifying Marxist groupings which continue to argue – against all evidence – that the best way forward is to hunker down in the Labour Party and wait. Having failed to transform Labour into a mass democratic workers’ party with Corbyn as leader, in our view it is totally unrealistic to put that forward as a strategy now when Starmer and his ilk have a stranglehold on the party. Nonetheless, the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL) for example, urge Corbyn not to stand outside of Labour because: “It would not create a viable working-class socialist political profile against Starmer’s ‘pro-business’ orientation, and it would give Starmer a chance to solidify his control by bundling out left-wingers who back Corbyn”. It will, they argue, just “multiply the many no-hope attempts at electoral splinters”. (Labour’s NEC votes on banning Corbyn, 27 March 2023)

How much more solidified does Starmer’s control need to get before the AWL abandons this policy of passivity? Do they really suggest that, no matter what events develop, new left formations can only be ‘no-hope attempts’? They cynically point back to the period from 2010 to 2015, when there were no decisive steps towards a new mass workers’ party. However – as a result of multiple factors, including the economic crisis, the current strike wave and the experience of Corbynism – there will be far greater opportunities for the development of a new party in the next period than there were then, which will be further fuelled by the experience of Starmer in office.

And there were important steps forward taken in the years prior to 2015. The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) – in which the Socialist Party participates – was launched in 2010 in order to provide a banner for anti-austerity candidates to contest elections. It is not – then or now – a mass party of the working class but nonetheless was able to have an impact on events. In 2015 TUSC had stood 135 candidates in the general election and had the official backing of the RMT. When, in early July 2015, the Unite national executive council decided to nominate Corbyn rather than Andy Burnham one reason given was to counter the growing support for TUSC supporters campaigning in the union for a new party – giving a real impetus to Corbyn’s leadership bid following his endorsement by the RMT executive.

The RMT had agreed to support TUSC in 2012. Its role was very important in fighting to push Corbynism forward. A relatively small trade union of around 80,000 members, it gave more money to Jeremy Corbyn’s campaigns than any other union except Unite, with 1.4 million members. Despite considerable pressure, including John McDonnell addressing their Annual General Meeting (AGM), they did not vote to re-affiliate to the Labour Party, with a majority seeing that they could more effectively back up Corbyn from the outside. Instead, the 2017 AGM agreed to consult the RMT membership on a political strategy “to create a mass party of labour that fights in the interests of the working class, as Labour arguably now has the potential at least to be that party”. As part of the consultation it was agreed to “seek answers from the Labour Party” including on “what powers affiliation would actually give the union, if any” and whether it “would still be free to pursue its own policy agenda”.

A Special General Meeting in 2018 then agreed not to re-affiliate but to continue to spend RMT’s political fund on candidates who support RMT policy. Issues that RMT members weighed up were the continued implementation of attacks on RMT members’ terms and conditions by Labour-led transport authorities, reflecting the continuation of right-wing ‘business as usual’ by Labour local authorities; and the Corbynites failure to democratise the party, including restoring the role of the trade unions as the key element in creating a federal, democratic Labour Party. This meant that re-affiliation would not guarantee the union a seat on the NEC and the RMT would only have gained around 16 delegates at Labour Party conference out of 2,700 or so. On balance, delegates voted not to hand over their political fund to the Labour Party as a whole, but to continue to use it to back the Labour left, while also leaving room to choose to back other candidates who stood on a platform in RMT members’ interests.

Drawing wrong lessons

Supporters of the AWL within the RMT vociferously argued against this position, calling for affiliation to Labour at all costs, as did other groups inside the party. Socialist Appeal was particularly hysterical, saying that we in the Socialist Party were ‘sectarian’ while simultaneously insulting RMT members’ intelligence by suggesting we had “helped to derail the RMT’s affiliation”. In the same article, they attacked us for “lectures from the side-lines about how to reclaim Labour” when “members are already doing this, thank you very much” (Reject the Blind Alley of Sectarianism, 21 February 2019). Unfortunately, however, RMT members’ concerns about the failure to transform Labour under Corbyn’s leadership have been totally confirmed. The programme we fought for to transform Labour was never adopted by the leaders of the left who constantly sought compromise with the pro-capitalist right.

Socialist Appeal, the AWL and the rest bear a share of responsibility for this. They also attempted to limit the struggle to those who held a Labour Party card, rather than seeing it – as both the RMT and the 88,500 who signed up as ‘registered supporters’ to back Corbyn in 2015 did – as a battle to create an anti-austerity party, removing the Blairites and opening the doors to all those who wanted to fight for a left programme. We wholeheartedly threw ourselves into this struggle, including proposing our affiliation to Labour in order to aid the battle against Labour’s right, which was not taken up by any Labour left groupings. We participated in the Corbyn-supporting Momentum grouping until we were excluded by the leadership for not holding Labour Party membership cards, a decision that Socialist Appeal and the AWL did not oppose and, in some areas, were to the fore in implementing.

All this experience demonstrates why Marxists should not now be cowering in the Labour Party or just ‘protesting’ their expulsion, but fighting for steps towards a new mass party of the working class. Even if in the future there is a new mass left surge within the Labour Party, an unlikely scenario, the best way to prepare for that, and for the workers’ movement to exert pressure on Starmer and co, is to take steps towards a new party now.

If this year’s Unite conference, for example, was to agree that the union could support candidates outside of Labour, and was then to agree to back Jeremy Corbyn and others, it would exert enormous pressure on Starmer’s New Labour. Back in 2004, when Labour’s executive booted out the RMT for a similar decision, they were not actually following the Labour Party rule book, which – while it prohibits individuals from supporting candidates outside Labour – says nothing about affiliates doing so. The rules remain the same today and Unite is Labour’s biggest single financial backer. A major crisis would be created however the Labour leadership reacted. If they reluctantly allowed Unite to back Corbyn and other left candidates while remaining affiliated, the pressure on other unions to take the same path would be enormous.

Passivity and abstract ‘revolutionism’

It is no surprise that Socialist Appeal tries to avoid calling for steps to a new party at all costs. This trend split from the Militant Tendency (now the Socialist Party) in 1991. We had led the magnificent mass movement against the poll tax, with a peak of eighteen million non-payers, which had defeated the tax and led to the resignation of Maggie Thatcher. To give a glimpse of the scale of the victory, since 2010 central government funding of local authorities has been cut by around £15 billion. In contrast, scrapping the poll tax and replacing it with council tax required the Tory government to put an extra £4.3 billion into local government in one fell swoop – in current prices equal to about half of the total amount cut over the last thirteen years.

In the aftermath of the poll tax movement, the majority of our organisation agreed that in Scotland we should begin standing candidates in elections independently of Labour. The newly formed Scottish Militant Labour (SML) won four seats on the Glasgow council in May 1992. This was just weeks after the Tories’ victory in the general election, in which Tommy Sheridan came second in Glasgow Pollok with 6,287 votes (19.3%), ahead of the SNP. In all, from May 1992 to February 1994, SML polled 33.3% of the total votes cast in 17 local council contests, winning six.

Socialist Appeal condemned this move as a threat to “forty years work”. At every stage, they chose to prioritise the formal question of holding onto Labour Party membership cards over the class struggle. Even prior to their leaving our party over the ‘open turn’, their key leaders – Rob Sewell, Alan Woods and Ted Grant – tried to argue that the Militant-supporting Labour MPs, Dave Nellist and Terry Fields, should secretly pay their poll tax in order to maintain their positions. This was when hundreds had been jailed for non-payment, including 34 of our members. Their proposal was voted down and Terry Fields was among those jailed, enormously boosting his authority among working-class people.

Over the following thirty years, Socialist Appeal has continued to insist on the importance of remaining buried in the Labour Party, claiming that their “work in the mass organisations of the working class was of a long-term character”. So far removed from reality has this position become, with even the quietist Socialist Appeal now banned from Labour, they rarely mention this approach now, instead focusing on completely abstract ‘super-revolutionary’ propaganda. But they have not in reality changed their long-term position that a mass left-wing force will only develop through the Labour Party and no other avenue. As they put it in their 2023 World Perspectives document, Starmer’s inevitable “attempt to implement a policy of cuts and austerity will provoke an explosion of anger, which eventually will find an expression inside the Labour Party, beginning with the unions, which, in spite of everything, still retain their link to the party”.

What kind of new left party?

Rather than state this openly, however, they totally avoid the question by arguing that “calls for a new left party” are a “red herring; an organisational solution to what is at heart a political question”. They point to how “the left had power in Labour” but “all of this was squandered, and turned to dust because those in charge of the Corbyn movement were afraid to do what was necessary”. But they do not say a word about what is necessary now. How should delegates to the affiliated unions’ conferences vote on their political funds? Should Corbyn stand? Should he initiate a new party? There is no answer to any of these concrete questions.

The AWL are no different. One of its leaders, Martin Thomas, grudgingly recognises that the experience of Syriza in Greece – going from 4.8% in 2009 to winning the general election in 2015 – or the successes of Jean-Luc Mélenchon and France Insoumise in France are not totally excluded in Britain, although, he argues, far less likely than in those countries. However, he says: “If such a ‘left party’ could be developed in Britain, then it would represent the worst wing of Corbynism, not the best. It would rally the more electoralist, reformist, nationalistic, and populist strands of the Corbynite movement. It would probably have scant democracy”. (Corbynism, Pacts and Left Parties, 26 February 2022)

Clearly, there is a real danger that a ‘new left party’ could have these characteristics and be run in a top-down way by some of those at the centre of the Corbyn project. However, that is not an argument to oppose a new party, but rather to campaign for it to have a socialist programme and for it to be an open, democratic party of the working class, with trade unions playing a central role. The AWL and Socialist Appeal’s cynical pessimism bears no resemblance to a serious Marxist approach.

Small groups predicting the failure of new left formations will not prevent them from coming into existence. On the contrary, given the hundreds of thousands who have flooded out of the Labour Party, it is inevitable that new attempts at a left electoral alternative will develop. Right now the Greens are attempting to step into that vacuum, standing an unprecedented 3,300 plus candidates in the local elections. Undoubtedly they will pick up votes from some who are looking for an alternative to the left of Labour. Some refugees from Corbynism have joined the Greens on that basis. Expelled Labour Wirral councillor Jo Bird, a pro-Corbyn Jewish Voice for Labour candidate in an NEC by-election in April 2020 who polled 46,000 votes, is one, arguing that the Green Party shares her “commitment to social and environmental justice”.

The real character of the Greens’ leadership was, however, shown clearly when the pro-capitalist wolves were circulating around Corbyn’s Labour leadership. On the grounds of ‘combating a crash-out Brexit’, in August 2019 the Green Party’s sole MP Caroline Lucas came out for a government of national unity, involving all parties including the Tories and the ‘Independents for Change’ group of Blairite MPs – the conscious, if premature, saboteurs of Corbyn. The only proviso set by Lucas was that the cabinet members be women! Unsurprisingly, her Labour choices – Yvette Cooper and Emily Thornberry – were not Corbynites, while Diane Abbott was, at first, mysteriously ‘forgotten’. In the 2019 general election, the Greens had an electoral arrangement with the Liberal Democrats – who were part of the vicious austerity coalition government from 2010-2015 – standing down for them in 40 seats; but stood against Jeremy Corbyn and other left Labour candidates.

Some socialists have joined the Greens, but as a party, it accepts the constraints of the capitalist system. They do not see society in class terms, never mind seeing the need for the working class to have its own political voice. If a trade union was to affiliate to them it would have no power over decision-making. On the contrary, Caroline Lucas actually praised the destruction of the rights of trade unions within Labour in the pre-Corbyn era saying that, “to his credit, Ed Miliband has inched towards some kind of reform. So too have some union leaders, who perhaps see they would have more influence if they were not so clearly tied to one party – just like the RSPB [Royal Society for the Protection of Birds] can campaign effectively for birds, whoever is in power”. (Honourable Friends: Parliament and the Fight for Change) She seems not to have noticed that with 43% of British birds ‘at risk’, the ability of the RSPB to influence events via polite lobbying of establishment parties has proved very limited!

The votes for the Greens are a symptom of a search for a new party, which will develop regardless of the wishes of the SWP, AWL and Socialist Appeal. Rather than avoid the issues facing the working class, whether via abstract revolutionary rhetoric or clinging to the Labour Party and predicting disaster for anything that develops outside – or both in the case of Socialist Appeal – Marxists should be fighting for concrete steps towards the working class founding a new party of its own. Backing motions calling for unions to open up their political funds and support workers’ candidates in the general election would be a good place to start.