On October 27, 1998, the first and so far only federal government consisting of the SPD and the Greens was elected. Gerhard Schröder became Chancellor, the former Bürgerschreck – or ‘terroriser of the bourgeoisie’ – Joschka Fischer, Foreign Minister, and Oskar Lafontaine Finance Minister. What can we learn from the experiences of this coalition today?

If you look at the election results at the time, it becomes clear how drastically the political landscape has changed since then. The social democrats (SPD) became the strongest party with 40.9% of the votes cast. Unionised employees were relieved that the sixteen-year era of CDU Chancellor Helmut Kohl had finally come to an end. Although there was no euphoria, there was hope for a more social policy. There was to be bitter disappointment.

The role of the SPD

The SPD had shifted significantly to the right in the preceding years and old principles were thrown overboard. For example, the “Sozis” – or ‘moderates’ – agreed to the de facto abolition of the basic right to asylum. They also went along with the privatisation of the state-owned postal and railroad companies. The so-called “big eavesdropping attack”, a significant expansion of the police’s ability to spy on people’s private lives, would not have been possible without the SPD. These policies were an expression of the fact that the character of the party had changed.

With the collapse of Stalinism in 1989/90, all ideas that represented an alternative to the existing system came under massive pressure. Any idea of state ownership of the economy was countered by those in power with triumphalist propaganda. Not many organisations could stand up to that or didn’t want to stand up to it. Until then, there was still an active, left-wing base in the SPD that could rely on a broad base in the workplaces, but this increasingly disappeared. This meant that the leadership of the party, which had been defending capitalism for decades and had a bourgeois character, was able to dominate the entire party. This brought about a qualitative change in the party, from a workers’ party with bourgeois leadership to a purely bourgeois party that no longer differed significantly from the CDU.

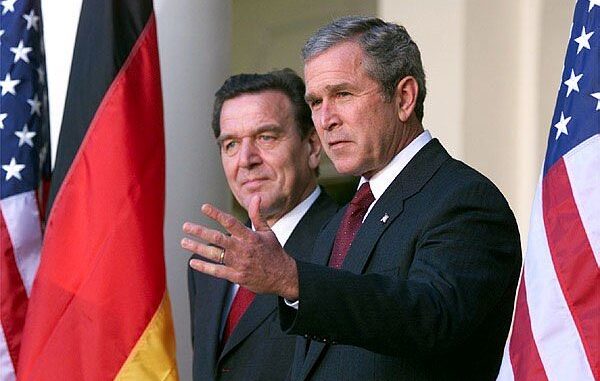

Schröder and Lafontaine

There had been power struggles in the SPD for years, with changing staff at the top. During the 1998 election campaign, the then party leader Oskar Lafontaine and the powerful Prime Minister of Lower Saxony, Gerhard Schröder, agreed in a small circle that the latter should enter the race as the SPD’s top candidate. There were political differences between the two that initially did not come to fruition with the historic victory. When it came to governing, things quickly turned into a scandal. Schröder stood for the “new” social democracy. The British Prime Minister Tony Blair from the Labour Party was the inspiration. He continued the basic principles of the neoliberal policies of his Conservative party predecessor, Margaret Thatcher. This was just packaged in a more modern way.

The “new” social democracy thus said goodbye to its original idea of achieving reforms, i.e., improvements for the working class, within the framework of capitalism. Instead, it was now at the head of the forces that were attacking the “welfare state” that the party had helped to achieve in earlier years. Lafontaine played a key role in driving the SPD’s shift to the right. However, adopting neoliberalism went too far for him. As Federal Minister of Finance, he spoke out in favour of slight government intervention, for example, taxing the financial markets using the Tobin Tax. He also advocated that some large corporations should pay higher taxes. However, this contradicted the neoliberal trend of the time. A few years after the collapse of the opposing system, big capital felt that it was in a strong position internationally and wanted to achieve far-reaching successes at the expense of the employees and their unions, in order to significantly increase profits.

Therefore, Lafontaine’s very limited goals went far too far for the capitalists. The right-wing British tabloid, The Sun, raised the question of whether the former Prime Minister of Saarland was the “most dangerous man in Europe”. At that time, the “Handelsblatt” reported massive pressure from the most important German companies behind the scenes. It was clear that a decision on the direction of the government was pending. Schröder spoke out loud when he said that he would not pursue “politics against the German economy.” Lafontaine took the consequences and resigned as finance minister and SPD chairman.

Tornados over Belgrade

Schröder and co. can claim to have made history. In a negative sense. With the collapse of Yugoslavia there were several bloody wars. In 1999, the conflict between the disadvantaged Albanian majority in Kosova and the Serb-dominated rest of Yugoslavia came to a head. The long-standing oppression of the small ethnic group by the Yugoslav military became more intense. In response, the nationalist Albanian Liberation Army (UCK) increasingly resorted to armed struggle.

There were military clashes with a number of deaths. The Albanians were supported by the major Western powers, especially the USA. They had an interest in weakening Serbia, which was traditionally an ally of Russia. Western media and the established parties carried out massive propaganda with the aim of intervening in the Balkans against the rest of the former Yugoslavia that was ruled by Slobodan Milošević. Ultimately, they did this under the cover of NATO because there was no legitimacy in the UN Security Council. It was, in bourgeois terms, a war that violated international law.

The fact that the Bundeswehr (German military) took part was a historic decision by the red-green government. For the first time since 1945, German soldiers took part directly in a war. Like before in World War II, German Tornado warplanes bombarded Belgrade. A bitter dispute raged within the SPD and the Greens. The membership of the two parties were brought into line with massive demagoguery and lies, in which Defence Minister Scharping (SPD) and Foreign Minister Fischer (Greens) stood out. This had a demoralizing effect on the anti-war movement. Up to that point there was a strong pacifist wing of the SPD and Greens that was part of the peace movement. The fact that a government that was considered “left-wing” was waging war unsettled and confused many people. As a result, the protests were nowhere near as large as they would have been had they been directed against a bourgeois-conservative government.

Riester pension attack

One of the SPD’s few promises during the election campaign was a pension reform that would have corrected some of the deteriorations of the Kohl era. However, the opposite was the case. On the one hand, the Labour Minister Riester, former deputy chairman of IG Metall, reduced the level of the statutory pension. On the other hand, he promoted purely private pension provision, which has been associated with his name ever since. It was a step towards the partial privatisation of pensions. The champagne corks were popping at the large financial groups such as Allianz. This brought the government into its first major conflict with the unions. Things were particularly bubbling in the IG Metall union. As a result, the union leadership around Klaus Zwickel was forced to mobilise against the project of their old friend Walter Riester. There were (half-hearted) actions and work stoppages. This nevertheless represented an important development for German conditions. Ultimately, however, this only served to let off steam. The leadership of the IGM, like that of the entire DGB trade union confederation, did not want a confrontation with “their” SPD-led government. So, the Riester pension became law and older workers in particular began to turn away from social democracy.

Nuclear phase-out

The phase-out of nuclear energy was also decided in the first legislative period. At first glance, this represented great progress. However, it was associated with many pitfalls. In particular, the extremely long running times of nuclear power plants brought the environmental movement onto the streets. The protests against the transport of the Castor nuclear containers in the early 2000s were particularly directed against the Environment Minister Jürgen Trittin and the Greens. This was also an important experience for the anti-nuclear movement with the party that it previously viewed as its parliamentary representative. Many activists no longer wanted to have anything to do with the Greens.

9/11 and its consequences

The attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001, had a dramatic impact on world events. US imperialism took advantage of the situation to expand its influence. Afghanistan was the first to be looked at. The country was occupied under the pretext that they wanted to eliminate the perpetrators of the attacks. After the al-Qaeda attacks, Chancellor Schröder promised the United States government “unrestricted solidarity” and took part in this war. This expressed the increasingly self-confident role of German imperialism, which increasingly aggressively represented the interests of capitalists all over the world politically, economically, and militarily. The forced restraint of the post-war period was over.

In this context, we must also consider the massive conflict with the US government over the Iraq War that broke out two years later. There were no humanitarian reasons why Schröder and Fischer did not take part in the war. The economic interests of German capital, as well as other countries such as France, Russia, and China, were different from those of the USA. They were also concerned that the United States would play a dominant role in the region and worldwide. Parts of those in power also feared further destabilisation of this geo-strategically important region.

Election campaign 2002

When the next federal elections took place in autumn 2002, the fate of the red-green federal government seemed sealed. The two parties were well behind in the polls. There was a surprising turn in the election campaign that led to the victory of the existing coalition. There were two reasons for this. There was a devastating flood on the Oder with extensive damage. The Chancellor knew how to cleverly present himself as a crisis manager and promised quick help. The election campaign was also overshadowed by the looming armed conflict in the Middle East. While the federal government rejected the war against Iraq, CDU leader Angela Merkel clearly sided with the US government. There was a clear majority of the population who rejected the war. That was the deciding factor in the outcome of the election. Even if red-green cleverly drew this card, the federal government did support the war, albeit indirectly. It was a great advantage for the US Army that it could use the German bases as normal for its supplies and was given overflight rights over German territory.

Agenda 2010

During the term of the red-green government, unemployment rose to over five million people. The pressure grew that something had to happen to change the situation. For years, big business has been running a constant campaign through its lobby associations and the media that “reforms” in their interests are finally coming. Internationally, the German economy was also considered the “sick man of Europe”. The capitalists were longing for a neoliberal liberation to improve their own competitiveness against increasing international competition. From the perspective of the rich, under Helmut Kohl’s government there were only (too) small steps that never came close to the scale of the major attacks by Reagan in the USA and Thatcher in Great Britain. In terms of foreign policy, the banks and corporations were largely satisfied with the federal government. Now they wanted results on the domestic front.

In February 2003, Chancellor Schröder surprised friends and foes with a government statement that presented the Big Bang: Agenda 2010. Behind this project was the greatest attack on social achievements in German post-war history (if one considers the historically special situation in the wake of the unification of the former FRG and GDR in 1990 and the dramatic social consequences). Many of the measures adopted back then continue to have a negative impact today: the massive expansion of temporary work, the disenfranchisement of the long-term unemployed in particular through Hartz IV (what is now called citizen’s money), the commercial restructuring of the healthcare system or the reduction of the tax burden for corporations, to name just a few examples. A movement against social cuts developed, particularly in East Germany. Action alliances with local demonstrations were formed. Today’s Sol (CWI Germany) members also played an important role in these local groups and in the first large nationwide demonstration on November 1, 2003, in which 100,000 people took part and which was initiated by the SAV (predecessor organisation of Sol). This was the initial spark for a wave of company strikes in autumn/winter 2003, as well as the movement of Monday demonstrations and trade union mass demonstrations which involved hundreds of thousands in April 2004. However, they were used by the union leadership as a way to let off steam instead of a prelude to a serious struggle.

This development also had far-reaching political consequences. With the Electoral Alternative for Work and Social Justice (WASG), a new party emerged in which disappointed former supporters of the SPD, active members of the trade unions and unemployed people and workers who had previously not been politically visible, came together. This development was linked to a whole series of catastrophic defeats for the SPD. The highlight came in May 2005 when the former stronghold of North Rhine-Westphalia went overwhelmingly to the CDU in the state elections. Schröder responded with a surprising manoeuvre and initiated early elections, among other things to prevent the WASG from developing into a serious threat. In the subsequent election campaign, Schröder came up trumps again and achieved a surprisingly good result. Nevertheless, the red-green coalition was voted out and the Merkel era began, with the SPD as junior partner.

Conclusion

The red-green federal government will go down in history as the one that took the militarisation of German foreign policy to a new level. With Agenda 2010, the most extensive social cuts to date were carried out in Germany after the Second World War. As a result, there was further alienation and even a break with the two parties among parts of the labour and environmental movements. With the founding of the WASG, an approach developed for an alternative to the SPD and to the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS). The latter was strongly represented in the East but very weak in the West. On the one hand, this was due to its past as the successor party to the Stalinist East German Communist Party (SED). On the other hand, it was part of state governments (Berlin, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) that also took part in social cuts.

The fact that the WASG, not least under pressure from Oskar Lafontaine, united with the PDS to form the party DIE LINKE sparked a lot of hope for a strong all-German party to the left of the SPD. We warned back then that accepting the pro-capitalist policy of government participation with the SPD and the Greens, which the PDS had accepted, would become a birth defect that would prevent DIE LINKE from developing into a mass socialist party. The current deep crisis in the party, including the recent split around Sahra Wagenknecht, confirms our assessment at the time. It is important to draw the right conclusions from these events.

For socialists, this means that, against the background of a deep, multi-layered crisis of capitalism, we need a programme that transforms today’s fight against wars, for social improvements and against the consequences of climate change, etc. with the aim of a fundamentally different society, a socialist democracy.