Despite two years of negotiations, nine rounds of talks, extended deadlines, last-minute pleas and much hand-wringing the World Health Assembly failed to agree a new pandemic treaty on 27 May. It was meant to ensure the world was better prepared for future pandemics than it had been for Covid-19.

After 700 million confirmed cases, seven million deaths worldwide and unknown numbers still suffering Long Covid, better preparation is desperately needed.

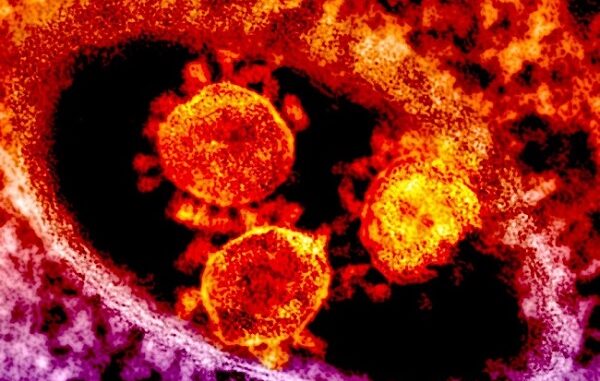

The new coronavirus swept around the world frighteningly quickly from late 2019. Within a year or so the Covid-19 pandemic reached almost every country. Tiny Pacific island states and North Korea were among the last to report cases. Turkmenistan is now the only country not to have reported a single case, most likely due to government censorship rather than any public health measures.

All experts agree the next pandemic is a question of ‘when’ – not ‘if’. The risk of new human infections spreading from one side of the world to another in days is higher than ever before. Crowded cities, intensive livestock farming, tropical rain forest exploitation, wars, climate change, poverty and global travel due to tourism, trade and migration – humans are increasingly exposed to viruses and bacteria that don’t respect national borders.

A possible candidate for a new pandemic is the H5N1 bird flu virus. An outbreak began in 2020 which has killed tens of millions of poultry and countless wild birds. In March it was identified in cattle and goats in the USA – a cross from birds to mammals. Future viral changes would become closer to being able to infect and then transmit between humans.

Whenever new viruses are identified it is vital that information is shared quickly with laboratories and governments around the world. Chinese virologist, Zhang Yongzhen, identified the Covid-19 DNA sequence in early January 2020. After informing the government he published the results, despite the regime’s attempt to stop this.

Restrictions have been placed on his lab since then, most recently this April when the lab was closed for ‘renovations’. After sitting outside with a placard for a week, which was widely shared on Chinese social media, his team were allowed to return. It appears there are differences within the regime over how to handle his position.

The pandemic exposed other governments also conflicted over their handling of the crisis. These pressures emerged during the treaty negotiations.

Many countries have poor public health services, lacking laboratories and scientists to identify new viruses. Less developed countries are the most likely places where new infections will emerge. Unequal access to medical services, new vaccines and treatments means any new pandemic could quickly spread.

Billions of Covid-19 vaccines were bought up by rich countries, leaving poorer countries at the back of the queue. Canada, Australia and the UK had bought 11.1, 9.9 and 7.6 vaccine doses per person respectively by June 2022.

Meanwhile, South Africa was able to buy the equivalent of 0.5 doses per person. The African Union bought 330 million doses – just 0.2 doses per person.

“When push comes to shove, we cannot count on rich countries to do the right thing”, said Maaza Seyoum, Global South convenor of the People’s Vaccine Alliance. “The poorest countries in the world have ended up at the back of the queue, creating the sense that some lives matter more than others”.

Governments’ responses to previous disease outbreaks have usually been panic, followed by disinterest once the crisis is over. This time was supposedly going to be different. While Covid still raged in 2021, leaders of 21 countries signed a letter calling for “a new international treaty for pandemic preparedness and response… we must be guided by solidarity, fairness, transparency, inclusiveness and equity”. Among the signatories was then Tory prime minister, Boris Johnson.

Fine words, but reality turned out differently. World Health Organisation (WHO) progress towards a new Pandemic Treaty crept along, often getting stuck. A hundred and ninety-four member states have been negotiating a global plan to deal with ‘Disease X’. This should be in everyone’s interests, but tensions and disagreements soon emerged. Parked behind every country’s negotiators are their own ruling class’s interests. Meanwhile, working class and poor peoples’ voices are not heard.

Right-wing politicians claim a new treaty will undermine ‘national sovereignty’. Despite Johnson having called for a treaty, his Tory allies denounced the negotiations. The then Minister for Health Andrew Stephenson told parliament on 14 May that the government would only accept the outcome “if it is firmly in the UK’s national interest to do so”.

But UK pharmaceutical and other profit-seeking ‘interests’ aren’t those of health and other key workers exposed to new infections, of workers in crowded workplaces or living in overcrowded homes, travelling on public transport, at school or college and so on.

In the same debate, Tory former home secretary Suella Braverman brazenly said that “in the light of serious errors of judgement, poor leadership and, I am afraid, well-chronicled conflicts of interest that have subsequently emerged”, she was “profoundly sceptical” about the “ability to manage a global pandemic”.

Yet she wasn’t describing the Johnson government she was a member of, despite the worst Covid record of any West European country and a string of scandals from contracts awarded to ministers’ friends to Downing Street parties.

Likewise, the then Tory MP Philip Hollobone described WHO as “a failing, mega-expensive, unelected, unaccountable, supranational body which is increasingly under the influence of the global elite”. This could be a good description of a multinational bank. Before becoming an MP Hollobone was an investment banker.

Other Tory and Democratic Unionist Party MPs repeatedly claimed WHO was attacking ‘national sovereignty’. So has Nigel Farage. The same arguments are being dragged out as during the Brexit debate.

Of course, none of them mention the ‘unelected, unaccountable organisations controlled by a global elite’ dictating the lives of billions of people across the planet as well as in the UK. Mega-corporations controlling energy and food production, IT and media, manufacturing, mining and more, exert enormous pressure on governments everywhere. These politicians speak on their behalf while aiming to divide working-class people on national lines.

Donald Trump repeatedly called for the US to withdraw from WHO when president, suspending payment to it in 2020 (a measure subsequently reversed by Joe Biden). The pandemic treaty negotiations brought similar attacks from his supporters. Fox News headlined a story, ‘Disease X: Critics say Biden admin selling out US sovereignty with WHO treaty’. (16 April 2024)

Brad Wenstrup, Republican chair of the US House select subcommittee on the Covid pandemic, attacked the call for companies to consider sharing proprietary information. The treaty must not “infringe upon the rights of the American people or the intellectual property of the United States”.

China’s government also insisted the co-operation called for in the treaty should be voluntary and not restrict its own decisions.

Medical advances are often made with public funding, but they do not belong to ‘the people’. Instead, ‘intellectual property’ is grabbed by corporations for profit. The pharmaceutical industry is based on exclusive rights to what should be shared knowledge benefiting everyone.

Governments of the wealthier countries dominating the global economy wanted the new treaty to commit poorer countries to share viral samples and data of new outbreaks as early as possible. But these same wealthy governments refused to share test kits, personal protection equipment (PPE) and vaccines fairly during the covid pandemic.

A group of Asian, African and Latin American governments wanted pharmaceutical corporations to pay towards monitoring new viruses. Corporations opposed this, on the grounds that if they refused to pay up they could be denied access to these materials – something they would certainly enforce on their customers.

“You had universal access to information, but no access to vaccines”, resulting in the “wrath of public opinion”, said Chikwe Ihekweazu, a WHO assistant director-general who led the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention during the pandemic. “That, I think, is at the heart of the trust deficit – and at the heart of the very difficult discussions happening”.

New vaccine manufacturing capacity in Africa is being set up in South Africa and Rwanda, each with a capacity of about 50 million doses a year, but this is nowhere near the needs of 1.4 billion people. Once produced, vaccines need refrigeration while being stored and distributed. The infrastructure for this does not exist in many parts of the world.

Had pandemic preparations been taken seriously there would have been stockpiles of PPE in every country, as well as a global network of laboratories and manufacturing capacity on standby, ready to produce tests, treatments and vaccines as soon as these were identified.

Some governments were better prepared, particularly the East Asian countries hit by the SARS virus in 2003, but most were woefully unprepared. Britain’s Public Health Laboratory Service was broken up by Labour under Tony Blair, privatising parts of it along with NHS Logistics. Tory and LibDem austerity then left the UK particularly vulnerable.

Watered down WHO proposals

During the negotiations the WHO draft treaty was repeatedly watered down, weakening action that governments should take to protect people throughout the world. It called for high income countries to give WHO ten percent of their tests, vaccines and treatments and sell it a further ten percent “at affordable prices” for distribution to poorer countries. This still left 80% to be sold to the highest bidders. But even this was not enough for Big Pharma, the world’s major pharmaceutical companies.

Despite all the fine words and absence of concrete measures on these key issues, the final wording still was not agreed at the World Health Assembly’s meeting at the end of May. Instead, it was agreed to keep talking. However, most observers have concluded that talks could continue for another year or two and still not overcome these sticking points. If Trump is elected in November it is even less likely any meaningful treaty will ever be agreed.

This sorry outcome confirms that the World Health Organisation, like the United Nations, cannot resolve issues where ruling classes have competing interests. The Pandemic Treaty negotiations failed because each negotiating team was accountable to their own governments – and in turn these were pressured by big corporations to ensure their right to maximise profits was not infringed.

Working class and poor people throughout the world have different interests. No-one is safe while parts of the world remain without PPE, test kits, medical services and, once identified, vaccines and treatments.

Socialist measures are vital to invest in public health, and production of medications and vaccines for need instead of profit. That requires public ownership of the pharmaceutical and medical supplies industries and their democratic planning on an international basis.

Just as socialism is impossible in only one country, health will always be at risk from future pandemics until these measures are taken by working-class movements across the world.