2017 marks the 100-year anniversary of what became known as the ‘Great Strike’ in Australia. Sometimes referred to as the ‘New South Wales General Strike’, this huge upheaval actually spread to all the eastern states of Australia. In many respects, it was probably the most intense period of class struggle that Australia has ever seen. It encompassed around 100,000 workers, lasted more than two months, and affected Australia’s key industries.

The strike was a major class confrontation. The most important sections of the organised working class faced off against the combined forces of the state and the capitalist class. Despite the determination of the workers, the strike was eventually defeated. One hundred years on, this strike is worth studying, not just out of historical interest, but because it contains lessons that the labour movement will need to draw upon in future battles.

The strike took place in midst of World War One. When the war began in 1914, a patriotic mood developed but as the hostilities dragged on people’s attitudes began to change. The economic conditions played a big part in transforming the situation. Inflation saw prices rise dramatically, and profiteering was rampant. As wages and living conditions were undermined, workers were forced to ever more shoulder the burden of the ‘war effort’.

In 1916 the government suffered a significant blow losing a referendum on conscription to the armed forces. This provided a big boost to the labour movement who led the campaign for a ‘No’ vote. Patriotism was waning somewhat, giving way to radicalisation and a new mood of militancy. People moved to recoup some of the financial losses they had suffered in the previous years. 1916 saw a huge increase in strike activity with over 1.7 million work days lost. This was the highest level of strikes ever recorded to that date.

The conscription issue split the Labor Party with Prime Minister Billy Hughes going on to form a new Nationalist government. In NSW, another former Labor leader, William Holman, had recently assumed power. Like Hughes, Holman had been expelled from Labor and went on to join with the right-wing Liberals to form the Nationalist Party. Now avowed anti-Labor men, both Holman and Hughes, were keen to strike a blow against the unions who they correctly saw as responsible for the conscription defeat. It was during these tumultuous times that the 1917 strike kicked off.

The spark

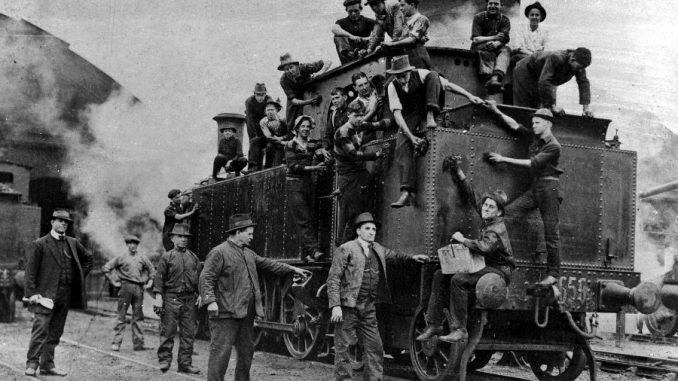

The spark for the first outbreak of the strike was ignited at the Randwick and Eveleigh railway workshops in Sydney. These were two of the biggest workplaces in NSW. The state-owned railways wanted to introduce a new card system. The cards would be used as records for time and motion studies and the skilled workers correctly perceived them as a way to speed up their work rate and undermine the control they had over their jobs.

There is no doubt that part of the motivation behind this dispute was an attempt by the government to both weaken the control of the trade unions and to cut across a growing appetite for revolutionary ideas. While the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had been banned prior to the strike their radical pitch which opposed the war and promoted direct action still held much sway.

But, at the same time, the railways were running at a loss. This however was mostly due to rising interest rates on commercial loans as a result of the war. The Railway Commissioner considered that he could do little about the interest rate rises but he could take other action. He increased fares and freight costs and wanted to reduce labour costs by speeding up work. The workers saw this as yet another attempt to shift the costs of the war onto them and they were not going to have it.

The Railway Commissioner pushed for the card system to be trialled for three months. Both the workers and management had made promises of ‘no extra claims’ during the war and the workers rightly considered this a breach of that agreement. While the trade union leaders were angling for a compromise with the government, the workers were preparing for a fight. They took matters into their own hands on August 2 by refusing to cooperate with the implementation of the card system.

On that day, the metalworkers from the Randwick and Eveleigh workshops led around 5700 people out on strike. Little did they know that this act of rank and file militancy was to have widespread ramifications.

Strike spreads

While the railway workers had legitimate concerns about the card system, the fact that the strike spread like wildfire to other workplaces says something about the general mood that existed. In reality, the card system was just the straw that broke the camel’s back. This strike was an expression of the widespread discontent that existed in society, as a whole.

The first group of workers to support the strike were the fuelmen who loaded coal on the trains. All coal held by the Railway Commissioner was declared by the strikers to be ‘black’. The idea that other union members would not touch ‘black’ goods, or facilitate the work of scabs, was the main way the strike spread.

Rail was the key form of transportation and the industries that relied on it were the first affected. The reduction in rail services immediately affected the coal mines as well as the wharfs, as waterside workers refused to load ‘black’ coal onto ships. Many workers in other industries went on strike as they did not want to travel to work on scab trains.

In the first few weeks of August the strike gained significant momentum. The stoppages of the wharfies led to strikes across the entire waterfront. By mid August waterside workers and seamen in both Queensland and Victoria had also stopped work. Employers attempted to replace some of the strikers with scabs but this only added fuel to the fire as unionists continued to both boycott ‘black’ goods and refused to work with scabs.

Workers take the lead

In the first instance, the union leaders involved did not support the strike. In fact, many did their utmost to prevent it from going ahead. Throughout the dispute they were desperate for a resolution and to avoid things escalating. They were however facing a tinderbox situation. The workers had had enough and were hell-bent on resisting the government and boss’s offensive.

While the workers had to drag the union leaders kicking and screaming into the strike, they were hopeful that once in they would carry out their responsibilities and lead it. A Defence Committee composed of leading officials from different unions was established to co-ordinate the strike and to negotiate with the government.

One of the most incredible aspects of the Great Strike was the level of initiative taken from the ranks. Time and time again workers refused to wait for calls from the leadership and instead just organised meetings on their own and decided to walk off the job. By the second and third weeks of August, in addition to shipping being paralysed, the strike had spread to many rural areas. Manufacturing workers, meat workers, storeman, packers and drivers had all stopped work alongside tens of thousands of others. It is estimated that in total more than 2.5 million work days were lost during that Great Strike. While it wasn’t at the stage of an all-out general strike, all the key sectors of the economy were affected.

Huge meetings were held on a daily basis at the Domain in Sydney and on the Yarra Banks in Melbourne. Mid to late August actually saw in excess of 100,000 people attend protests at the Domain on several occasions. It wasn’t just workers but also their families, and others like anti-war protesters that attended. At the time these were the biggest protests Australia had ever seen. The mood was both jubilant and militant with people regularly singing the IWW song ‘Solidarity Forever’.

Scabbing and repression

The strike was ascending throughout August and the government was keen to stem the tide. They stepped up their efforts to recruit scabs, who they called ‘volunteers’, by setting up National Service Bureaus in all the major cities. Newspapers promoted the recruitment of scabs, labelling the strikers unpatriotic. The government appealed to layers of the middle class, conservative types from rural areas, and more backwards elements of the working class to fill the jobs of the strikers. Many students from prestigious universities and private schools were used. The strike very much polarised society along class lines.

Some people scabbed as they perceived the strikers to be betraying the war effort while others were given financial incentives. Both the government and employers offered to keep scabs on after the strike and pledged to either demote or withdraw the accrued benefits of those who refused to return to work. Camps to accommodate scabs from rural areas were set up in places like Taronga Park and at the Sydney Cricket Ground. Many were sent to work on the waterfront while others were deployed at mines as it was especially crucial for the government to maintain the supply of coal to ensure industry and transport could continue to run.

All the forces of the establishment and the state were mobilised against the striking workers. The media coverage was extremely biased with barely a single paper reporting on the events in an objective way. The government enrolled hundreds of special constables, and issued them with revolvers, to support police operations. Street skirmishes between strikers and scabs were regular and there were occasions when things turned very ugly. For example, in one incident a scab called Reginald Wearne shot two striking workers during a confrontation. Mervyn Flanagan died as a result while Henry Williams was wounded. Disgracefully, Wearne, the brother of a Nationalist politician, ended up getting off the charges on the grounds of self defence.

Repression was also ramped up with the arrest of three trade union leaders. Despite the fact that they actually tried to prevent the strike they were charged with conspiracy to incite the action. While their plans were much more modest, the government accused the union leaders of orchestrating a rebellion, claiming they were out to sabotage the war effort and overturn capitalism. Far from stemming the tide however the arrests only angered workers further and provoked more workers to get involved.

Workers continued to join the strike up until the first week of September. It was around this time however that the government cut off all negotiations and declared the Defence Committee an illegal organisation. The Defence Committee timidly agreed to ‘adjourn indefinitely’ and proposed that the strike be called off. Despite the official call being made, it took some weeks for all the workers to actually return to work. The attitude of the leaders was vastly at odds with the workers, most of whom wanted to continue the action and spread it even further.

Leaders capitulate

To take it further however would have meant a real showdown with the government. Any further escalation would have posed the question of which class actually rules. There was no doubt that the government went into the dispute well prepared. The union leaders however had been dragged into the strike and they had no discernable strategy to win. Most were schooled in the art of arbitration and saw their role as merely negotiating within the framework of the system, rather than challenging it. From their point of view there was no way forward and with that in mind they moved to end the strike, even if it meant a setback.

The Defence Committee recommended a return to work on the government’s terms which meant an acceptance of the card system on the railways. The workers considered the deal an outright capitulation. The union leaders attempted to sell the deal by explaining that there was no way to win but many were not convinced. In some places people voted against returning to work. In other places the union leaders did not even conduct a vote, they simply issued instructions.

While the strikers were reluctant to give up, as different groups of workers were goaded into returning, it was clear that the tide had turned in the government’s favour. Once the employers sensed a government victory on the railways, they sought to replicate the result and offer no concessions to strikers elsewhere. Some employers didn’t even offer the strikers their jobs back. They simply locked them out and replaced them with scabs. There is some evidence to suggest that this was encouraged by the government as a means of encouraging men to find employment in the army as they were desperate for troops.

Unavoidable defeat?

The union leaders explained that the defeat was unavoidable. They suggested that things were stacked in favour of the government and to prolong the strike further would have led to an even worse result. Some suggested that the timing was wrong as the government was prepared for the strike to spread, even stockpiling coal. It is true that some coal was stockpiled. The government had been expecting industrial strife as they were preparing to put the issue of conscription back on the table. But more important was the fact that the loading of coal was not stopped during the course of the strike.

Yes, workers connected to the coal industry had withdrawn their labour but scabs were filling some crucial gaps. The government desperately needed to maintain a supply of coal to industry and for exports. If the supply of coal was stopped it would have stalled the economy entirely and turned the tables on the government. To do this however would have required a strategy to deal with the mass scabbing effort. While initially some sectors had ground to a halt, this was overcome with the widespread use of scabs.

Tens of thousands were regularly attending protests and mass meetings, but at no stage did the union leaders call for those people to be mobilised at mass pickets to stop scabs from doing the work of the strikers. While it would have been difficult to picket every workplace, it would have definitely been possible to organise pickets at key centres of economic activity. The scabbing effort had a real impact and it is clear that the union leaders underestimated this. While no strike victory is assured, it is very possible that a more militant approach could have turned the situation around.

Narrow politics

Unfortunately, the strike also highlighted a lack of unity amongst the many craft based unions that existed at the time. With dozens of unions present in some sectors, there were many workers who were members of unions that did not adhere to the strike and this undermined its effectiveness. It is estimated that in NSW only a third of union members participated in the strike. Even on the railways, the divisions meant that the strike was not fully solid. Disappointingly, little was done to try and overcome this during the dispute.

There was a united response from the federal government, the NSW government, the state, the employers and the media. While important sections of the trade union movement and some community groups did come together, the movement was nowhere near as unified as their opponents and there was no plan in place to consciously extend the strike to strengthen it. As far as it did happen, it was largely the result of rank and file initiative and spontaneity.

While the divisions in the union movement were a significant problem, they could have been overcome with a more far-sighted leadership. The strike took place at a time when revolutionary upheavals were erupting all around the world. Only two months after the rail workers returned to work, the successful Russian Revolution ushered in the first real workers’ government in the world. Discontent was brewing in many countries and the mood in Australian society as a result of the war meant that the potential to win the strike was there, as were the possibilities of transforming it into a political struggle for more significant change.

The problem however was the reformist politics of those that dominated the leadership of the trade union movement. Most of the leaders were politically conservative and suffered from trade union narrowness, whereby their attention was solely concentrated on the immediate problems in the workplace. In relation to politics they were focused purely on parliament. While a mass strike brings the union movement into the realm of national and international affairs, the leaders did not really consider that they had a role to play over and above the basic issues of wages and conditions.

In 1917 the politics of the workers movement in Australia was lacking depth. The immaturity of the socialist movement meant that the reformist union leaders faced no concerted challenge. The most prominent revolutionary group of the time, the IWW, had been smashed earlier in the year. The state had declared the IWW illegal and its leaders were jailed. At that stage the Communist Party had yet to be formed so the best militants and revolutionaries were lacking political direction. The defeat of the strike however forced many militants to reassess their politics and the way in which the unions were organised. A new debate about how to strengthen the workers movement was provoked in the aftermath of the defeat.

It took until the first week of December for the last of the striking workers to return to work. Going back was a bitter experience for many. Scab workforces had been established in many workplaces and thousands of strikers were victimised as a result of the action they took. Rank and file leaders were particularly targeted for reprisals by the bosses. A number of unions were also deregistered as punishment and several scab unions were set up to replace them.

Aftermath

While Australia saw an explosion of industrial action in 1916 and 1917, there was a dip in strike action immediately after the defeat of the Great Strike in 1918. That said, things turned around in a spectacular way in 1919. The movement was able to take advantage of improved economic conditions after the war had ended. In fact, in 1919 the number of work days lost even surpassed that of 1917!

The arbitration system that was in place meant that unions were officially registered by the state and they played a role in the creation of Awards that regulated wages and conditions. Arbitration had been generally supported by the trade union movement in the aftermath of the defeated strikes of the 1890s and the system was established proper in 1905. That period saw the economy grow and regular increases in wages, so to the reformists the system seemed to work.

The idea of arbitration stems from a belief that workers and bosses have common interests and that the capitalist state is impartial. The onset of World War One, and the changed economic conditions, combined with the defeat of the Great Strike, led many to challenge theses ideas. The fact that a number of unions were deregistered actually pushed them to explore organising methods outside of the arbitration structures. Many turned away from the courts and to strikes as the chief weapon for winning improvements.

While some unions took years to recover from the defeat of the Great Strike, others swung back into activity relatively quickly. The railway unions were knocked back for a number of years but in the mines and on the wharfs demoralisation from the defeat was not as severe. The defeat actually led to a general shift to the left in the union movement. In the period after the strike a number of union elections were held where the old leaders were replaced with militants. In NSW a group that became known as the ‘Trades Hall Reds’ took over the labour council. In what was an acknowledgment of the limits of craft unionism, the idea to form One Big Union became immensely popular.

In reality, the defeat of the Great Strike was a key turning point which led to the growth of a new, and even more militant, mood in the Australian trade union movement as well as a shift towards socialist ideas. On the back of the successful Russian Revolution, the Communist Party in Australia was established in 1920. This move was an affirmation of the weaknesses of both the ideas of reformism and syndicalism. The Labor Party was also affected. While it was limited, Labor adopted a socialist objective in 1921.

While the Great Strike was ultimately unsuccessful, it must be recorded as a truly incredible event and one of the highlights of Australian working class history. It proved to be an extremely formative process and it showed the potential power that the working class holds under capitalism. When workers stop work en mass society grinds to a halt. If that power can be harnessed, and a revolutionary lead is given, the working class have the ability to sweep aside capitalism and to usher in a democratic socialist society that truly serves their interests. While that perspective was not realised in 1917, there will be scope to fulfil it in the future.

Be the first to comment