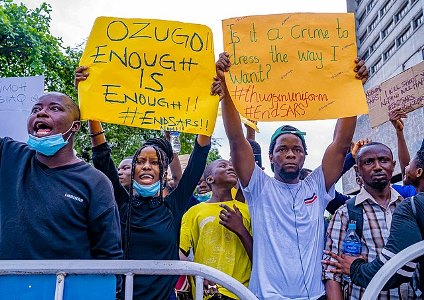

Nigeria has passed through nearly a month of turmoil. Video footage of the hated SARS police unit killing a man and driving off in his car was the spark for mass protests.

Years of frustration, disappointment, poverty and anger exploded into a mighty mass movement fundamentally undermining the regime of Buhari. It put into question the very future of not just of the current government system, but the country itself.

This tremendous, inspiring youth movement had an electrifying impact on many parts of the country. This willingness to struggle was in complete contrast to the leaders of the country’s trade union movement. Just two weeks earlier, they called off a general strike, at the last minute, and signed an agreement backing the government’s austerity policies which the general strike was meant to oppose!

Officially, Nigeria was supposed to be in the middle of celebrations marking the 60th anniversary of independence from Britain. But what really is there to celebrate? A recent Senate committee report said that it would take “41 years” for Nigeria to have a stable electricity supply; that on its own is an indictment of both the Nigerian ruling class and the capitalist system.

It was not accidental that at the height of the #EndSARS movement President Buhari called a meeting of all living past heads of state of both civilian and military administrations, and received their backing. After all, the whole rotten, corrupt system was being questioned. Looting, corruption and bribery are endemic as the country’s oil and gas wealth is systematically stolen. Yes, the low paid police and military intimidate and collect bribes at roadblocks, but the real corruption starts at the top. It is why the capitalist politicians fight expensive and desperate “do or die” election campaigns to get themselves into positions where they can loot one way or another.

This movement against SARS, and its replacement unit SWAT, brought to a head the simmering anger. But the 20th October shooting down of unarmed demonstrators at the Lekki Tollgate on Lagos’ Victoria Island provoked an explosion of outrage. While the numbers killed and injured in Lekki are disputed, with regime supporters talking of ‘fake news’ and manipulated videos, the violence is not. On 23 October, Buhari said that the security forces had exercised “extreme restraint”, yet 51 civilians were killed nationally, along with 11 police and 7 soldiers since the protests began.

The violence was not the result of the initially peaceful protests. Rather, it was in response to the sometimes brutal attitude of the police to demonstrations and more fundamentally to the state and ruling party sponsored attacks on the demonstrators. In the same way that “do or die” politicians hire unemployed or criminal elements to attack rival parties and intimidate voters in elections, now they have sponsored attacks on the demonstrators. Agent provocateurs were planted with the aim of provoking confrontations to give the authorities to excuse to act against protesters, and, at the same time these thuggish elements also profited from the ensuing chaos. It is clear that some of these attacks had the open backing of security forces; the BBC reported that “video evidence suggests that they were encouraged by police officers to target the demonstrators”. In an overwhelmingly young country, 18 is the median age, where two-thirds of the youth are either unemployed or underemployed, there are those who can be hired to carry out such deeds.

But this violence has taken on a life of its own with attacks on warehouses storing Covid-19 “food palliatives” in a third of Nigeria’s 36 states. This aid is meant for distribution but has not been distributed over the past months. The fact that some of this aid had become rotten or found in politicians’ homes did not help the government’s claims that they were being stored in preparation for the second wave of Covid-19. These claims are not believed in a country where politicians boast of providing “stomach infrastructure” in return for votes. The assertion by a leading Lagos politician that he was keeping “palliatives” in his house for distribution to people on his birthday was barely believed, but if it was true it just showed how aid was being used as bribes. Significantly, it was not simply criminal elements looting these warehouses, the poor were as well. This is hardly surprising in a country where about half the population, over 100 million people, are described as living in “extreme poverty”.

This storm was brewing for some time. Even before Covid-19 hit, Nigeria was in a severe social and economic crisis, alongside the Boko Haram insurgency in the north-east of the country and clashes with both ethnic and agricultural origins in central areas. The fall in oil prices was leading to Nigeria suffering its second recession in four years. Inflation is taking off; currently, food prices are rising at nearly 17% annually. In addition, there is huge unemployment (the official rate is 27.1%, i.e. 21.7 million people), with no social benefits. The resulting poverty is worsened by widespread underemployment and non-payment of wages in both the state and private sectors.

The result is both disappointment with Buhari, who was elected in 2015 with a promise of change, and continuing anger at the elite. It is not accidental that in London, in the UK, Nigerian #EndSARS protesters demonstrated outside the expensive downtown house owned by Tinubu, the “National Leader” of Buhari’s APC.

Union leaders

This explosive situation was one of the key factors why the trade union leaders called off the general strike scheduled to begin on 28 September. They feared starting a movement which they could not control. Significantly the trade union federations maintained a long silence over the anti-SARS protests, issuing their initial mild statements only after the Lekki shootings.

While many activists were not surprised at the trade union leaders’ actions – they have behaved in similar ways before – for many young people it seemed to show that the union leaders were simply part of the system. At the same time, there was deep hostility to politics. September’s governorship election in Edo state summed it up. The two main candidates had previously stood against each other in 2016, but since then they had both switched parties. So the 2016 APC candidate was the 2020 PDP candidate and vice-versa!

At first, the anti-SARS protesters were anti-political, refusing to let political speakers address the rallies. This included the widely known democratic, but not socialist, activist, Omoyele Sowore, who is currently being prosecuted for calling “RevolutionNow” demonstrations. As the EndSARS protests developed there was a significant change; political action was seen as being necessary and the idea of a youth party, one which broke with all the rottenness of the ruling parties and their satellites, gained support.

But just being young, or new, is not a political programme. While Buhari and co. are mainly old, there are ‘newer’, ‘younger’ Nigerian politicians who are part and parcel of the rotten system. For instance, in 2007 Dimeji Bankole at 37 was the youngest ever Speaker of the national House of Representatives, while now 45-year-old Yahaya Bello is governor of Kogi State, and says he is the “number one youth in Nigeria”.

The issue of programme, what a party or movement will do, is key if it is going to make a fundamental change.

Unfortunately, there are signs that at least some of those who have claimed leadership of the EndSARS protests are supporters of capitalism, arguing that corruption needs to be removed and then Nigeria will “develop”. Seun Kuti, a very well-known activist and musician and the son of Fela Kuti, argued that the list of five demands put forward by those heading the #EndSARS protests were “elitist” as they did not seek to end oppression when the divide was between the ruling class and the “common man”.

The statement issued on 23 October by the ‘Coalition of Protest Groups’ was clearly orientating mainly towards the 2023 elections. It said nothing about fighting poverty, oppression or corruption, and talked of representing “the different coalitions; from celebrities to activists, legal minds to strategists, journalists to entrepreneurs, etc.” This list significantly included ‘entrepreneurs’, i.e. capitalists, but not labour, the working class or poor.

At best, such an approach does not deal with the fundamental questions facing Nigeria, namely the inability of capitalism to develop the country and the impact of the repeated crises that world capitalism. But, at worst, there is the danger that a few will use this movement as a stepping stone for their own personal advancement.

Working people and youth need their own party

The Democratic Socialism Movement (DSM – the CWI in Nigeria) has long argued that working people and the poor need their own party. This can fight for their interests and build a mass movement that puts into power a government that will end the rule of capitalism and, with socialist measures, fundamentally change the country. The DSM, with others, launched the Socialist Party of Nigeria, as a force that can begin to challenge the pro-capitalist parties and argue for the creation of a mass working peoples’ party.

The repeated opportunities lost when labour leaders refused to challenge the ruling class do not mean that the working class is weak. The 2012 general strike was an example of how labour and youth can spearhead a movement that could have carried through the socialist revolution that is required.

The EndSARS movement gave a glimpse of what struggle can do. Its strength forced the government to grant concessions. But it is clear that the ruling class were simply looking for a breathing space. Currently, with the movement ebbing, the government is starting to issue threats and trying to prepare the way to try to use repression against protests. The fining of three TV stations for alleged “unprofessional coverage” of the EndSARS protests and the warning to them of a possible “shutdown” in the future is just one of the government’s efforts to re-establish its control.

This illustrates how much still remains unresolved. The challenge now is to resist any repression, consolidate the gains that have been won, discuss the lessons of both the EndSARS movement and the aborted September general strike, while preparing for the inevitable future battles in order to fight to change society.