The 23 June Summit of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) agreed to the deployment of a military force to northern Mozambique. This was the belated response of the regional elites to an armed insurgency that has been underway in the Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado since October 2017. On 19 July, South African National Defence Force (SANDF) units began arriving in Pemba, the provincial capital. These are the “leading elements” of the “SADC Standby Force Mission”. The numbers of troops could rise to 3,000, backed up by attack helicopters and naval patrol ships, if SADC’s April draft plan is implemented in full.

A disaster is unfolding in Cabo Delgado. In 2020, alone, there were 570 “violent incidents”. Nearly 3,000 have died, so far and over 700,000 have been displaced. Atrocities against the local population are being committed by both the insurgents and the Mozambican army and security forces. For many, the SADC intervention may seem necessary to put an end to the possibility of the insurgency spreading. There is widespread revulsion at the horrors of the barbaric methods of the insurgents. They include beheadings, as with ISIS in the Middle East, the kidnapping of school children, and the enslavement and rape of girls taken as wives of the insurgents, like Boko Haram in Nigeria. But the SADC intervention will not only fail; it will aggravate the crisis.

Whose interests?

Although SADC is being positioned as the ‘public face’ of the military intervention, the major imperialist powers are also playing a role. Troops from Rwanda – a non-SADC country and recipient of United States military aid – arrived in Mozambique a few days before the SANDF. The United States and Mozambique’s former-colonial power, Portugal, have both deployed “trainers” to assist the Mozambican army. Earlier in July, Portugal and France successfully pushed for the European Union to agree to a “military training mission” which will begin in September. Kenya and the UK are also reported to be “helping” the Mozambican army and security forces.

The discovery in 2010 of vast natural gas reserves in the seas off of the Cabo Delgado coast is at the heart of both the insurgency and the willingness of so many foreign capitalist governments to assist the Mozambique government militarily. There has been an unprecedented inflow of $120 billion of foreign direct investment into Mozambique to develop extraction. Leading the pack is France’s Total, with a $20 billion investment, and the US’s ExxonMobil with a $30 billion investment. Also involved are Italy’s Eni, the UK’s BP, and the China National Petroleum Corporation. Behind the oil multinationals are institutional investors. South Africa’s Standard Bank has lent $485 million to Total. All are expecting a return on their investments.

The southern African economy is in a desperate state. The ruling elites of SADC’s sixteen member countries preside over societies marred by deep poverty and huge inequality. They see foreign investments by multinationals based in the main imperialist countries as one of the few lifelines available to them. They need to generate sufficient economic growth to underpin their own wealth while staving off a social revolt. They are, therefore, desperate to prove that they can defend these investments.

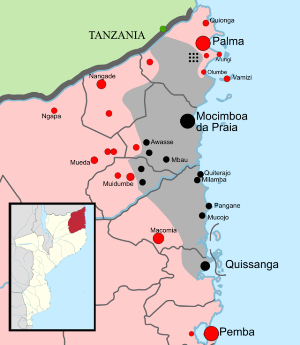

Accordingly, the political pressure on the Mozambican government to agree to an intervention increased significantly following the attack and capture of Mocímboa da Praia last August and Palma, in March, this year. Both towns are strategic hubs for the development of the gas fields. The attack on Palma led to Total temporarily suspending operations linked to ultimatums that unless the security situation was stabilised a full withdrawal of the multinationals – and their investments – would be posed. Total was no doubt backed up by French President Macron, who made his first ‘state visit’ to South Africa at the end of May.

Over the past 25 years, foreign military interventions in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Great Lakes region have had little success in creating “stability”. The opposite has been the case. Military interventions, leaning on different factions and groupings of local elites, have reinforced, prised-open, and inflamed religious, ethnic, and tribal tensions. They have propped up various dictators, ‘strongmen, and warlords. Outside of Africa, the US’s incredible twenty-year occupation of Afghanistan has achieved nothing, with the reactionary Taliban making a bid to return to power!

Now SADC is preparing to embark on its own “open-ended” military intervention. The SADC force will be incapable of resolving the underlying issues driving the insurgency. A drawn-out and unwinnable conflict is all that lies ahead for northern Mozambique.

Corrupt elite

Mozambique is one of the poorest countries in the world. Its neo-colonial position within the world capitalist system makes the economy and government hugely dependent on foreign aid and ‘multilateral’ loans. No longer falsely claiming to be ‘socialist’, this ruling elite plays a parasitic role in looting both to enrich itself and build patronage networks to keep it in power. Sovereign debt has reached 110% of GDP, nearly double the IMF’s 60% ‘danger’ threshold for ‘developing’ economies. Much of this debt has been racked up by the elite awarding themselves state loans. $2 billion has been looted through loans using the future revenue of the, as yet, undeveloped gas fields as collateral. To put this in context, Mozambique’s entire GDP in 2019 was only $15.2 billion. In 2018, even before the pandemic worsened the situation, Mozambique was forced to restructure its debt. Between the government and so-called investors, creditors, and donors in the imperialist countries, the people of Mozambique are being bled dry.

The SADC military intervention will ultimately prop-up the corrupt Frelimo (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique / Liberation Front of Mozambique) government in Maputo. That has been its role across southern Africa, helping to prop up Zimbabwe under Mugabe and now Mnangagwa, the Swazi royal-dictatorship in eSwatini, and the squabbling elite in Lesotho.

This government, in turn, protects the political and business elite in Cabo Delgado itself. Frelimo-linked business elites, also beneficiaries of state-backed loans, have developed their own business empires exploiting the resources of the north. Often these have links to organised crime syndicates involved in smuggling ivory, gems, timber, etc. Mozambique has also developed as a key link in the heroin trade which travels from Afghanistan, through Pakistan, and across the Indian Ocean to Mozambique. From there, it is smuggled into South Africa for distribution there and in the West. Some commentators have speculated that Mozambican president, Filipe Nyusi, delayed agreeing to the SADC deployment because of fear that the Frelimo government’s links to these criminal syndicates would be exposed. The near-year of procrastination has likely been used to bury the evidence.

The huge inequality in Cabo Delgado has only grown as oil and gas investment has poured in. The established elites have positioned themselves to benefit from the sale of land and ‘concessions’ by-passing the local population entirely. Dangerously, these inequalities have acquired a tribal dimension. The Frelimo-linked business elite is predominantly based on only one of the three main tribal groups in the area. They use their wealth and political position to control jobs and business opportunities and use extortion against rivals. One of the final straws in the months before the insurgency began was the eviction of poor ‘artisanal’ ruby miners in favour of local business elites with links to mining multinationals. The SADC military intervention will defend this horrific status quo.

Insurgency

Anger at the Frelimo government, its local Cabo Delgado puppets, and the huge inequality they preside over, were essential in sparking the insurgency and continue to drive it. The insurgents are overwhelmingly young. The International Crisis Group describes the rank-and-file of the insurgency as “poor fishermen, frustrated petty traders, former farmers, and unemployed youth”. Many fighters are attracted simply by the possibility of pay in a situation of mass unemployment and limited economic opportunities. They are relatively small in number. Estimates range from 1,500 fighters and up to 4,000 when ‘support’ forces are included.

The insurgents have named themselves al-Shabab (Arabic for “the youth”) and sought explanations for poverty and inequality in Islamic scripture. They look for social change through a return to ‘traditional’ religious values. The implied link to the Somali-based al-Shabaab has been seized on by the Mozambican government, SADC, and the imperialist powers to justify the military response. But there is no evidence that any of the different transnational right-wing political Islamist groups initiated the Mozambican insurgency. All serious commentators agree that it is “homegrown”. The ideologues of al-Qaeda, ISIS and al-Shabaab in Somalia, and elsewhere in central and east Africa, are now however manoeuvring to hijack it. In the political vacuum that exists they, unfortunately, appear to be succeeding. The SADC military intervention will only assist this process. It will create a self-fulfilling prophecy as foreign ‘ideological fighters’ are attracted to the conflict as has been the case elsewhere in the world.

Guerrillaism’s legacy

Southern Africa has been home to several guerrilla movements within living memory. In the 1960s and 1970s, the worldwide struggle for national liberation against colonialism was fought in the form of guerrilla wars in southern Africa against colonial rule in Namibia, Angola, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. They were often supported by the then-Stalinist powers of either the USSR or China, whose very existence was seen as a living demonstration of the limits of the powers of imperialism and the possibility that it could be defeated. This confidence swelled the ranks of the guerrilla movements, particularly with youth who embraced the language of Marxism and socialism as the language of revolt. Southern Africa’s past guerrilla movements fought to throw off the yoke of colonial or white-minority rule.

The founders of Frelimo (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique/Liberation Front of Mozambique), in particular, declared the liberation struggle as a class struggle. Mozambique was declared a Marxist-Leninist state in 1977, although there were no signs of the workers’ control and management of society that Marxm Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky struggled for. In the areas that Frelimo liberated even before the collapse of the Portuguese colonial empire, following the uprising of the radical junior army officers in 1974 in Portugal, attempts were made to establish collectivized farming.

Unfortunately, without a clear understanding of the central role of the working class in the struggle for socialism, the models of bureaucratic and repressive rule Stalinism proved a dead-end. At the same time, the policies of both the former Soviet Union and China were against the overthrow of capitalism, as had occurred in Cuba, and in favour of negotiated settlements on a capitalist basis.

Although Frelimo, following the departure of large swathes of the Portuguese settler population, was compelled to take significant steps in the direction of state control of the economy, this was not on the basis of workers’ control and management. Furthermore, those who genuinely wanted to move towards socialism did not have a clear understanding of the impossibility of constructing a socialist economy on the basis of one country, especially one as economically underdeveloped as Mozambique. The struggle for socialism could succeed only on the basis of an internationalist approach, uniting the working class of the entire southern African sub-continent, especially with the powerful South African working class.

The limitations of the understanding of Frelimo leadership, combined with the pressures of the ruling bureaucratic elite of the former Soviet Union and China, which used the liberation struggles as chess pieces in their own quest for global influence, against each other and the US, doomed the model pursued by Frelimo to failure.

In Mozambique, the intersection of conflicting Soviet and Chinese interests playing themselves out upon southern African soil reinforced the ideological and political limitations of the Frelimo leadership. These prepared the way for the disastrous neo-liberal capitalist model Frelimo came to adopt that has brought Mozambique to the catastrophic economic position it finds itself in today.

The heroic struggles, nonetheless, played a critical role in weakening imperialism’s grip in southern Africa, and, despite SA’s direct military intervention and economic sabotage, snapped the cordon of white-minority rule and colonialism that shielded apartheid South Africa, contributing to the fall of apartheid itself.

In the more urbanised South Africa, despite the ANC’s attempt to emulate the methods of the struggle of all these countries, conditions did not exist for a successful peasant-based guerrilla war. Despite the heroism of the MK (the ANC’s armed wing) combatants, the end of white-minority rule was achieved through the struggle of the working class in the cities.

Dead-end

The southern African liberation movements were fighting to free the population from oppression. Political freedoms were not seen as an end in themselves, however. They were to clear the way to raise living standards through development, based on the nationalisation of what industry there was and economic planning. Secular education was seen as vital to produce the armies of administrators, teachers, technicians, and engineers this would require. The guerrillas were conscious of the need to win the political support of the populations they were attempting to liberate.

But nothing is left of this legacy in the region today. Liberation movements degenerated into neo-colonial capitalist governments, without exception. It is not possible in this article to analyse in detail the reasons for this. We will return to this in a future article.

Tragically, in Cabo Delgado, today, there is not even a shadow of the relatively progressive features of these past guerrilla movements. The right-wing political Islam that al-Shabab looks to is utterly reactionary. There is not even the pretence of support for democratic rights. The local population is to be subjected to oppression greater than that now faced, and controlled through a brutal regime of terror. They stand for the complete suppression of the rights of women. A medieval ‘caliphate’ is their model for a future society.

But the wheel of history cannot be turned back. Even a regional ‘caliphate’ based on all the areas of East Africa with large Muslim populations would remain trapped in a neo-colonial position within world capitalism. In practice, the ‘best’ that al-Shabab can hope for economically is to take over the smuggling syndicates and position themselves as new middlemen between the resources of the region and the capitalist multinationals. This was the direction in which the Taliban in Afghanistan and ISIS in Syria developed. The future for northern Mozambique, on the basis of the methods and ideas of al-Shabab, will be even worse for the local population than that which currently faces them.

Alternative

Despite the SADC agreement and the support of the big imperialist powers, it may take some time for the full “Standby Force” to be deployed. The pandemic continues to have an extremely disruptive effect on the region in new waves of infections and lockdowns. Both South Africa and Angola face deepening economic problems that will make the cost of deploying their militaries politically fraught. The weakness of the regional elites and their incapacity to manage their ‘own house’ may yet bury the 23 June agreement.

The deployment will fuel the very problems that sparked the insurgency. Even if there is some initial success in militarily suppressing it, the ground will be prepared for a more generalised revolt of the region against the Frelimo government in Maputo and its local representatives. The Cabo Delgado elite, the Frelimo government, and the regional elites, rather than strengthening their position, will realise too late that they have undermined it even further.

The workers’ movement across the region must take a firm position: NO to the SADC Standby Force Mission! NO to imperialist military interference in the region! Support must be given to the rural population in northern Mozambique to form multi-tribal and multi-religious self-defence groups to protect communities against the insurgents. Emergency aid and aid for economic development must be taken out of the hands of the elites who use their allocation to sow tribal and religious divisions. The vast natural resources of the region must be nationalised. The wealth and resources of Mozambique must be under the democratic control of local communities and used for the development of health, education, housing, roads, and other infrastructure. The debts of the Frelimo regime must be repudiated. The masses of Mozambique must refuse to pay.

Across the southern African region, new parties of workers and the rural poor need to be built as the vehicles for such a socialist programme. These parties will need to link up with the working class of the entire continent, and the entire world, in the struggle for world socialism. Only this can end the poverty and suffering of Mozambique and offer an alternative to the capitalist dead-end of under-development and armed conflict.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |