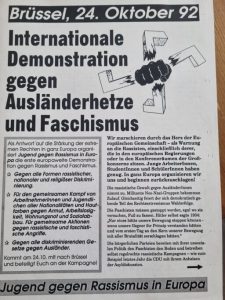

On the initiative of members of the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI), 40,000 people, mainly young people, demonstrated against racism in Brussels on 24 October 1992. This was the first international demonstration against the far right. This gave rise to the initiative, Youth Against Racism in Europe (YRE), which organised thousands of young people in many European countries and carried out many important actions and mobilisations against racism, Nazis and capitalism.

At the founding conference of the YRE in Germany, “Jugend gegen Rassismus in Europa – JRE”,200 young people were present. The organisation quickly became the most successful anti-fascist initiative in Germany, with groups in over fifty cities.

The background to the founding of YRE was a Europe-wide increase in fascist activities. In Germany, in particular, there had been the pogroms and murder attacks in Rostock, Mölln and Solingen. The federal government, all the established parties and the pro-capitalist media had declared the influx of asylum seekers to be the main problem of the country, the right to asylum was challenged (and then extremely restricted in 1993) and the fascists saw this as a boost. Nazi parties, like the NPD or DVU became popular. There were so-called “national liberated zones” in some, mainly East German, cities where fascists controlled the streets and migrants and anti-fascists could not be safe. Against this background, a mass movement against racist and fascist terror and against the growth of fascist organisations developed, especially among young people, but also in broad sections of the population, as a whole. YRE was able to develop quickly as the most dynamic, active youth organisation with a political programme.

But the growth of racism and fascism was not just a German phenomenon. After the collapse of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the Left and the workers’ movement were ideologically on the defensive. However, the victory of capitalism over the bureaucratic command economies had no positive effect on the living conditions of the masses. In the former Stalinist planned economies, there was huge deindustrialisation and mass unemployment. In the western capitalist states, the wage earners gained nothing from the victory of the capitalists.

This resulted in widespread discontent but given the bourgeoisification and rightward shift of social democracy and the lack of strong left and socialist alternatives, far-right forces were able to channel some of the discontent into racist channels. Outside Germany, in Austria, the FPÖ was strong, in Belgium the Vlaams Blok and in France, the Front National was growing, while in Great Britain the British National Party made itself heard, and in Sweden, there were far-right assassination attempts of left activists. But the backlash from young people and workers was also a Europe-wide phenomenon, albeit with varying degrees of intensity in different countries.

Internationalism

The YRE ultimately distinguished itself through three central aspects. The first was the international aspect. We said that fascists are on the rise internationally and that in many countries state racism was getting worse through discriminatory laws against migrants, deportations, etc. So we had to counter this internationally.

This started with the international demonstration on 24 October 1992, in Brussels, in which more than 40,000 young people from eleven different countries took part. When the CWI had worked out the plan for this demonstration in the spring of that year, there was also scepticism about the chances of success for this campaign, not least among German comrades. It was a bold plan, but we would have been satisfied at the time if 5,000 people had responded to our call. The fact that it turned out to be 40,000 was overwhelming, but it had to do with the events of the summer of 1992, including the racist pogroms in Rostock. However, the success of the demonstration is an example of the fact that as a socialist organisation you also need the courage to take bold initiatives if you have made a fundamentally correct analysis of the situation. At that time, more than 5,000 people from Germany, alone, travelled to Brussels. In the two weeks before 24 October, groups came every day to organise buses. In Aachen, bus companies even provided coaches free of charge.

We always placed a very high value on international exchange and campaigns. For example, in 1994, within six months, we organised an international camp in Germany, in which 1,200 young people participated. For this, we set up an office in Cologne, and formed a “camp team”, in which a few paid people worked, but, above all, many young comrades from different countries volunteered to make the camp a success. If we had organised such a camp a year earlier, probably twice or three times as many young people would have come, because by 1994 the anti-racist mass movement had already passed its peak. Nevertheless, the YRE camp, which was organised under the motto, “No Pasaran” (“They won’t get through – the battle cry of the anti-fascists in the fight against fascism in the Spanish Civil War) was a success and was honoured, among other things, with a special report on the music channel MTV.

The fact that police spies from Britain were also present at the camp only became known years later. That JRE was also being observed and infiltrated in Germany became clear to us at the time when members of the Bundestag (German parliament) were warned by the State Security Service that YRE was planning office occupations (a possibility we had only discussed internally).

Anti-capitalism

Secondly, the YRE said that the causes of fascism and racism must be fought, and has also clearly named them as being rooted in capitalist society. We did not leave it to moral appeals against the inhumanity of the Nazis. We explained that the growth of the Nazis is directly related to social problems, social contradictions, mass unemployment, social cuts and fears for the future. We also explained that the best struggle against racism is the common struggle for the social improvement of workers and youth of all nationalities.

Thirdly, we believed that the Nazis must be confronted, that true to the motto, “fascism is not an opinion but a crime”, they must not be granted the democratic rights they want to abolish. Thus, in direct mass mobilisations against fascist activities, we have repeatedly managed to prevent such activities. However, there was an important difference to the strategy of other anarchist and left-wing groups: we always tried to prepare such actions with the greatest possible publicity and to mobilise broad sections of the youth and the working class.

YRE festival in Liverpool

YRE actions

So there were countless actions on a local level where we prevented fascist meetings, and marches and ran information stalls many times. The JRE group in Lindau, for example, disguised itself as “Young right-wing extremists (JRE)”. It tricked its way into a meeting of the far right ‘Republicans’ and then brought it to a halt. In Kassel, we organised a demonstration with 1,800 participants, who went past the homes of Nazi cadres and outed them. In Cologne, we isolated the city’s top Nazi in his neighbourhood under the slogan, “No bread for Manfred Rhous” and actually got him to move away. We did neighbourhood work in East German housing estates. But we also took part in organising an apprentices’ strike in Siegen against the closure of a steelworks and organised protests in Stuttgart against cuts in youth centres. Certainly, the most successful actions were the prevention of two national party congresses of the fascist NPD in 1993.

At that time, together with Thuringian trade unionists, we chased the NPD through three central German federal states, which then went down in history as the ‘Tour d’Antifa’. At that time, the NPD had only announced that they would hold their party conference in Thuringia and we had mobilised hundreds of anti-fascists with enough cars to Erfurt. There we first received the information that the NPD was meeting in Fulda, where we then held a demonstration throughout the city, only to be informed that the fascists had started their party conference in Coppenbrügge in Lower Saxony. Together with local residents, JRE then besieged the conference building and forced the NPD to break off the event. A second NPD party conference was banned in Bavaria out of fear of similar protests by YRE.

Similar actions by YRE took place in other countries. In particular, YRE’s campaign in Britain against the British National Party headquarters in London was a great success, leading to several mass demonstrations and ultimately the closure of the BNP office.

We also organised anti-fascist concerts. At one of them, as part of the YRE national conference held in 1994 in Frankfurt am Main, Justin Sullivan, singer of the successful British band, New Model Army, performed among others. The British YRE even released a CD sampler, for which bands like Chumbawamba, Jamiroquai and Björk provided songs.

Almost legendary was the YRE stewarding and medical service for demonstrations. This was very important to us because we wanted to oppose both the Nazis and the police, who often acted against the anti-fascists. We mobilised in a united and organised way, as possible, to be able to provide effective protection for all participants in the demonstration. When there were violent clashes between supporters of the Turkish fascist Grey Wolves and anti-fascists at the big demonstration after the deadly arson attack in Solingen, the German Red Cross withdrew its paramedics from the demonstration for their own protection and only YRE paramedics were able to treat the injured.

Part of the workers’ movement

YRE did not claim to be the only force fighting the far right. It was always clear to us that we wanted to fight and mobilise with all parts of the left and the workers’ movement against the fascists. We formed many action alliances with trade union youth groups and with other anti-fascist groups, with left organisations. The demonstration in Brussels in October 1992 was supported by different committees of trade union youth organisations. The national youth secretary of the chemical trade union, for example, took part in the 1994 JRE national conference in Germany. When the German government discussed a ban on JRE in 1994, there was a lot of solidarity, not least from the youth of the DGB, the federation of German trade unions.

But the YRE was certainly the fastest growing youth organisation at that time, although we were more like an organised movement than a permanent organisation. At its height in Germany, we had groups in more than fifty cities. There were certainly well over a thousand young people more or less firmly organised. Across Europe, the YRE certainly organised and activated many tens of thousands.

The attractiveness of YRE, at that time, was the combination of an open and welcoming organisational concept, the orientation towards mass mobilisations and direct confrontations against fascists, combined with the struggle against the causes of the growth of racism and fascism. In this way, YRE differed from autonomous antifa groups, which often acted in a closed and almost clandestine way, and appeared rather elitist. And the YRE was also differentiated from the attempts of bourgeois forces and social democrats to pursue purely morally-based anti-fascism, which did not address the state racism of the ruling classes or the social causes of racism and fascism.

Lessons

The YRE operated at a time when the workers’ movement and the left, in general, were very much on the defensive. Many young people who would have been involved in socialist youth organisations in the 1980s were only prepared to become active on individual issues, such as fascism and racism. We started from there and tried to explain the social causes of racism and fascism through educational work and discussions. Today, the social crisis is much deeper. Now with the AfD (Alternative for Germany), there is a right-wing populist party with fascists in its ranks that represents a new, dangerous phenomenon and has penetrated broad sections of the population.

Anti-racist and anti-fascist activities must be closely linked to the struggle against the capitalist crisis, social cuts and layoffs. In the face of the multiple crises of capitalism, there is a danger of growing nationalism. This can only be stopped by a convincing left and internationalist response. Many young people, but also older workers and the unemployed see these connections. Today there is again the chance to build strong organisations that lead the struggle against fascism and the struggle against capital. In Germany, in recent years, however, the left party DIE LINKE and its youth organisation linksjugend (‘solid) have missed the chance to build a strong left alternative to the established parties that can also push back right-wing populists and fascists. Instead, DIE LINKE’s course of adaptation to working within the system, not least in its participation in regional and city governments with the pro-capitalist Social Democrats and Greens, has enormously increased the space for the AfD.

This does not negate the importance of broad anti-racist campaigns by trade unions, left organisations and social movements, especially when it comes to preventing Nazi marches and other fascist activities. But the fascist swamp can only be drained if the causes are fought. And these lie in the capitalist system.

One thing, above all, should be taken away from the YRE: resistance must be international. Today, in view of the world crisis of capitalism, this is even truer than thirty years ago.