On April 9 the European Trade Union Congress has called for a demonstration in Budapest to protest against the summit of EU finance and economic ministers with a protest against cuts. We are using the opportunity to look at the situation in this country hit by the crisis and attacks by the right wing parties.

Hungary took over the Presidency of the European Union at the beginning of this year. This puts the country’s chancellor, Orbán, and his policies under the spotlight. The EU leadership is trying to ignore mounting criticism of his government over issues like the treatment of Roma, the new law against press freedom and his system of special taxes on foreign companies. There are disturbing reports of the growth of far right and fascist groups, an increase in racist and anti-Semitic attacks and even killings. Is Hungary a dangerous place to be? Is history repeating itself with Orbán playing the role of a new Horthy – the ultra-right military dictator of the early 20th century? Or is there an alternative that can stop this process, to ensure that the rights of workers and youth of all nationalities, including Roma, living in Hungary can be guaranteed?

Hopes and promises are not enough

Hungary was one of the first east European countries to restore capitalism after 1989. This was accompanied by enormous hopes in the minds of the masses and promises by the ruling elite that Hungarian living standards would quickly catch up with those in western European. Initially, high levels of investment helped to create the illusion that the future would be bright. But for ordinary people, reality turned out to be less than rosy.

Production or Gross Domestic Product shrunk between 1988 and 1993 by 20%. Real wages dropped by 20% between 1990 and1994 and another 18% from 1995-1996. Thousands of companies closed down, half a million jobs disappeared. Unemployment – a phenomenon which hardly existed under the state-owned planned economy, in spite of the stranglehold of Stalinist bureaucratism – reached 12%. Now today’s living standards in Hungary are 40% lower than the ‘EU 25’ average.

Since 1989, all of the country’s different governments have followed the road of privatisation. Half of Hungary’s economic enterprises were privatised within four years.

Because of its highly skilled labour and its strategic position close to Western Europe, Hungary was an attractive country for international capital and it therefore attracted more foreign investment than any other country in Eastern Europe. West European banks used the buying-up of Hungarian companies to soak up some of their excess capital. This sell-off to foreign companies left a majority of export trade under their control and profits went to these same companies.

75% of Hungary’s large companies, 90% of its banks and 95% of insurance companies are in foreign hands. By the turn of the millennium, 80% of GDP came from the private sector, reflecting the rapid transformation of the economy that had taken place.

One example of the catastrophic effects of the restoration of capitalism is the toxic chemicals disaster in Kolontár in October 2010. The dam at the MAL Aluminium Factory broke and toxic red sludge poisoned the whole area. Ten people were killed and 300 were left seriously ill. The Hungarian Stalinist bureaucrats who used to run MAL when it was in state hands, were themselves neglectful of many aspects of health and safety and the environment. However, when the plant was privatised, the group of investors who took over MAL – former bureaucrats linked to the Stalinists, then the “social democratic” MSZP – were able to run the plant without even the previous minimal legal restraints. The two owners at the time of the catastrophe had an estimated wealth of €145 million; the drive for profit is almost certainly the reason behind the collapse of the dam and this toxic waste catastrophe.

Notwithstanding the income from privatisation pouring into government coffers, both state debt and private debt rose dramatically. By the end of 1994 about one third of the budget was used to pay interest on the state debt. By 2008 it had reached 80% of GDP. As the economic situation worsened, private consumption was partially maintained through the growth of private credit to workers and poor people who developed unbearable levels of personal debt.

Twenty years after the restoration of capitalism, the balance sheet is clearly negative. Poverty is growing, with about a third of the population living below the acceptable level of subsistence – more than half of them children. Amongst the ethnic minority Roma, who are systematically oppressed and exploited, the situation is much worse. The majority of Hungarians can only survive by having more than one job.

As the crisis began to hit the Hungarian economy, for a short period, the high levels of employment in the public sector helped to compensate for job losses in the private sector. But, as cuts in the public sector increased, this came to an end. Western capital, which had moved in to take advantage of the cheap and highly skilled workforce, moved even further East, taking the jobs with them.

The deteriorating social conditions have affected the way many people now view the situation today compared with the past. In 1991, 40% of the population thought that “the old system (under Stalinism) is better than the new one”. By 1995, this had increased to 54%. Unskilled workers and people working in the agricultural sector favoured the old system by 65%, and even amongst entrepreneurs and intellectuals, 29% were in favour of the “old system”. Today about 60% of Hungarians believe that the country lost out when the system changed.

The global economic crisis hits Hungary

As if the situation was not sufficiently fragile, the global economic crisis has led to even more serious problems for Hungary. Within a year, unemployment rose by 25%, and company failures by one third. In 2009 the economy shrank by 6.3%.

The combination of a double deficit – in the state budget and in foreign trade – and the high level of private debt (the majority of which is in Euros) meant the Hungarian Forint lost enormously on the money markets in October 2008. The national financial system did not have the resources to stabilise the situation, so the EU, the IMF and the World Bank organised credits of more than €20 billion to “rescue” Hungary.

Hungary was the first member state to be given a loan from the EU, but the creditors made it a precondition that the state deficit should be reduced from that of over 10% to the Maastricht limit of 3%, meaning further attacks on the living standards of the Hungarian working class.

The devaluation of the Forint was another measure to put the burden of the crisis onto the shoulders of ordinary working class people. 70% of all personal credits were valued in Euros so their cost rose by 40% when the Forint was devalued. Today up to 40% of all borrowers are late in making repayments by a minimum of 30 days, many by 90 days and more. More than 700,000 Hungarians have problems in paying their debts. Tens of thousands of families have lost their homes as a consequence of not being able to repay their mortgages.

The international investors care little about the social catastrophe all this represents, but they are undoubtedly worried about the high level of what is owed to them. They are concerned not only about whether or not they get their capital back, but also about further collapses seriously threatening the European and world economy. In the context of the global economic crisis beginning in 2008, the high involvement of Western European banks in Eastern Europe and the estimated high level of non-performing credit remains a serious danger, threatening further collapses in the banking sector.

The social consequences of the economic crisis and the demands of the international markets, applied by the “social democratic” government of the MSZP (Hungarian Socialist Party), are wide-reaching. Unemployment is growing. Of the 10% unemployed, 30% are young people. Only 54.5% of the labour force are in secure jobs, the lowest figure in the EU. That means that 3.8 million Hungarians who could work do not have a regular job.

The cuts being implemented include cutting wages in the public sector, increasing the retirement age from 62 to 65, reducing a number of social benefits and raising Value Added Tax from 20 to 25%. The cuts in the budget for 2009-10 constituted 5% of GDP. These attacks, carried out in the name of the so-called left MSZP, have led to an increase in disillusionment and desperation, which, in the absence of a genuine working class alternative, have fuelled the growth in support for right and far right parties.

Governments change – policies stay the same

Following the rejection of the one-party Stalinist system in Hungary in 1989, the first election in the new capitalist ‘democracy’ was held in 1990. Since then, a continuous string of coalition governments (only once was a government re-elected) have held power. But despite the variety of parties, in essence, the policies barely changed. The two main players were and remain the MSZP and the Fidesz.

The MSZP arose out of the ruling party of the Stalinist state. It is not, of course, a revolutionary socialist party, but tries to depict itself as a social democratic party in the West European style. However, it has none of the traditions of the social democratic mass workers’ parties, which, in their early stages, represented the mass working class, and often, despite the pro-capitalist nature of their leaders, reflected the desires and struggles of the workers.

The MSZP, in fact, mirrors the position of what the social democratic parties have become. It is like New Labour in Britain or the different social democratic parties in Germany and Austria which have openly implemented pro-capitalist, neo-liberal policies and while still getting votes from part of the working class can no longer be regarded as working class based parties. During its two periods in power, in coalition with the liberal Free Democrats SZDSZ, from 1994-98 and from 2002-10, the MSZP has acted in the interests of capitalism and is responsible for these sharp and anti-working class “reforms”.

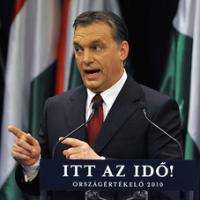

The Fidesz (Alliance of young democrats – now Hungarian Civic Union) dates back to 1988. Its leader, former member of the young communists, Viktor Orbán, became famous in 1989 at the mass rally on June 16th 1989 that marked the beginning of the end of the Stalinist dictatorship. The youngest speaker, he spoke with the sharpest anti-communist rhetoric.

Since then, Fidesz has evolved further to the right. Combining nationalist, chauvinist and racist propaganda with populist rhetoric and authoritarian measures, Fidesz ruled from 1998-2002 with the support of right wing parties like the nationalist and racist Smallholders’ Party that bases itself on a ‘Blood and Soil’ ideology. Today, Orbán and the Fidesz have the support of the Christian churches, big parts of the media and the richest capitalists of the country. In some parts of the country, it is hard to distinguish their programme from that of the neo-fascist Jobbik.

Paul Lendvai, a Hungarian author living in Austria explains: “Only those who look carefully behind the curtains know that the personal friends of Orbán – the richest Hungarian Forint-billionaires reaching from top-bankers to big businessman and oil-barons – control nearly everything”. One of those is the richest man in Hungary, Sándor Csányi, chairman and CEO of Hungary’s biggest bank, OTP. He has an estimated wealth of €600 million. This individual runs his own private secret service that, it is suggested, provides Fidesz with intelligence reports.

Fidesz and the right have only been able to gain support because the MSZP governments have been responsible for the most severe attacks on working class living standards. From 1995-98, for example, the “Bokros pact” reduced the deficit from 10% to 4.2 % of GDP as it reduced the state debt from $21billion to $8.7 billion. The international markets were happy with this policy of sharp cuts; the Hungarian people were not. A similar situation occurred again in 2008 when the MSZP government proved a reliable partner of international capital in implementing drastic cuts. In both cases, Fidesz benefited in elections from the discontent of workers with the cuts in wages and welfare system as the electorate voted against the MSZP government.

While both parties are capitalist, there are some differences between their policies. Many of Hungary’s former apparatchiks became “reformers” at the end of the Stalinist era and transformed themselves into the “new” Hungarian capitalists whilst maintaining their links to the MSZP. The MSZP in turn is the main partner of international capital in the country, whilst Fidesz has stronger links to those capitalists who resent the domination of the multinationals. This is reflected in the sometimes sharp rhetoric of Orbán against “international capital”, the IMF and others.

With little to differentiate their policies, each of the parties leans on the working class, particularly at election times, by introducing reforms that temporarily improve the living standards of the working class. They increase wages in the public sector, the national minimum wage or pensions only to zig-zag back at a later stage with new attacks, such as privatisation, cuts in social services and the state sector, new taxes or VAT increases, tuition and health care charges or rises in the price of gas, electricity and transport. All parties in Hungary subordinate the interests and needs of the working class to the profits of big, international as well as national, business.

This is because there is no genuine workers’ party in Hungary. The leaders of the current parties have their roots in the Stalinist state apparatus. They, as well as many of the richest bankers and capitalists, laid the basis for their huge wealth way back in Stalinist times by exploiting the opportunities offered by the pro-market reforms. As the Stalinist state collapsed, they became, often with the support of the old Stalinist bureaucratic caste, the new capitalist class. They used their “networks” after 1989 to benefit personally from the process of privatisation.

These vultures are to be found in all parties – the MSZP as well as the Fidesz. Ferenc Gyurcsány, Hungarian prime minister from 2004-2009 for the social democratic MSZP and known as the ‘Hungarian Blair’ came from the Communist youth movement. He made his first million in the privatisation process. After marrying into one of Hungary’s most important families, the Aprós, he climbed up the ladder to become a billionaire and one of Hungary’s richest people. When he came to power in a country where 20% or more live in poverty, he already had €14 million salted away in his savings. He was far from being anything like a workers’ representative!

In 2006, this same Ferenc Gyurcsány, as premier, made a speech at a meeting of the MSZP in which he said that he and his party had “lied throughout the last two years” to get votes. When this was made public, it was the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Mass protests and anger exploded, reflecting the total disappointment after 20 years of false promises. For weeks there were protests, demonstrations and even occupations. They were made up of ordinary people and youth. Students also were involved, speaking out against the ‘Bologna process’ that had been introduced against their wishes. In the absence of a left leadership, however, following the demonstrations and the storming of the TV headquarter in Budapest on September 18, 2006, a vacuum was left – a vacuum, which was, to some degree, filled by the Hungarian far right and fascists.

Far right, extreme right and fascist – dangerous mixture in Hungary

From the very beginning, even as the Stalinists were implementing pro-market reforms, the restoration of the market was accompanied by the emergence of right wing and far right ideologies. The first post Stalinist government was formed by the MDF, the Hungarian Democratic Front. In this organisation, built up with the support of the old Stalinist state apparatus in the hope they could use it to keep some influence, leading supporters propagated anti-Semitism and even a ‘Blood and Soil’ ideology. They organised the reburial in the country of the dictator, Miklós Horthy, in 1993 with the participation of 50,000 people, including seven representatives of the government.

All parties of the right – including Fidesz – link up ideologically to the Horthy regime and the idea of a greater Hungary. They play on the idea of bringing back into a “Greater Hungary” the 2.6 million ‘Hungarians’ living in Romania, Slovakia, Croatia and the Ukraine – territories separated from Hungary as part of the Trianon treaty at the end of the First World War. Fidesz, which uses symbols like the crown of Stephan, passed specific laws in 2001 and 2010 giving members of the Hungarian minorities in other countries extra rights, including the automatic right to become Hungarian citizens.

This leaves the neo-fascist Jobbik to take this idea to its logical conclusion, arguing that it “considers Hungarian-populated territories beyond the border to be part of a unified protected Hungarian economic zone”. This has nothing to do with supporting a people’s right to self determination, Jobbik is hostile to other nationalities and minorities, but is an attempt to help Hungarian capitalism dominate the region.

Once again, membership of international bodies is being used as a cover for reactionary changes. The Council of Europe has widely approved the new draft constitution proposed by Fidesz as it contains a superficial commitment to honour the EU’s Charter of Human Rights. However, it contains serious threats to workers’ rights, not least through the attempt to enshrine “the Christian roots of Hungary” in it. This is an attack on the rights of the Jewish and Roma populations and also entails a ban on abortion.

The real credentials of the Fidesz party are demonstrated by its attacks on press freedom and also the use of the “Manifesto of National Cooperation“, now called the Orbán Bull. This calls for “National Unity” – of blood and not including Hungarians with a Jewish or Roma background. Orban maintains his party is the “central political force” that is so strong it will not need “any useless discussions with the opposition“. Clearly the Fidesz government will move further in an authoritarian direction if the working class does not act to stop it.

Fuelling Fidesz’s authoritarian ideology is a deep-rooted anti-Semitism in Hungarian society. In 1920, Hungary was the first modern European county to adopt laws against Jews. This followed General Horthy’s rise to power, trampling over the blood and bodies of the 1919 Hungarian Commune under Béla Kun. Later, in the relatively short period of direct control by Nazi-Germany, in 1944 and 1945, more than half a million Hungarian Jews were killed. Stalinism in the period after the war also played on anti-Semitic sentiments. After 2008, the stereotype of Jewish finance capital “ruining the prospects of hard-working Hungarians” has been used increasingly. Today there are regular attacks on people from Jewish backgrounds, especially in Budapest.

Over recent years, racist and anti-Semitic propaganda and physical attacks have been on the rise and there has been a strengthening of various right, far right and even fascist organisations. The success of the neo-fascist Jobbik, which gained 17% in the 2010 election, made it into the international headlines. Linked to Jobbik is the ’Hungarian Guard’, a fascist, SA (Storm Troop)-type formation, organising about a thousand Hungarians who march through cities threatening to “clean them up”, especially those with a big Roma population. The Guard was formed in 2007. Its members wear uniforms and use symbols with a clear likeness to the Nazi “Arrow Cross” organisation which operated a terror regime from 1944-1945.

The first swearing in ceremony not only got wide press coverage, but the flags were blessed by Catholic, Protestant and Reform priests. The Hungarian Guard was banned in 2009 and relaunched in 2010 as the “New Hungarian Guard”. Roma people are presented in the Jobbik propaganda as parasites that have to be eliminated. They demand special camps for them with a double fence – something that existed only from 1944-45. They call for Roma families to be denied the right to raise children and for forced labour to be introduced. The Jobbik MEP, Krisztina Morvai, “advised” the “liberal-Bolshevist Zionists” to think about “where to flee to and where to hide”. As with other far right and fascist organisations, Jobbik uses anti-Semitic stereotypes blaming “Finance capital” (a code for: Jewish Finance capital) for the crisis and the situation in Hungary.

The other target of the far right and fascist groups is the Roma minority in Hungary. Many of the about 6-700,000 Roma are living in shanty towns, with hardly any chance to find work or get better education. Industrial collapse has hit the Roma population particularly hard, making it the socially most downtrodden part of society. Four out of five Roma people are without work. Jobbik and other far right and fascist groups combine Hungarian nationalism with anti-‘Gypsy’ rhetoric, seeking to blame the impoverished Roma minority for rising crime levels and spreading scare stories about their higher birth-rate threatening a “demographic catastrophe”. They do not restrict themselves to pure propaganda, but also use threats and intimidation. The increasing number of violent attacks on Roma people is linked to the activities and policy of Jobbik and the Guard.

Beside Jobbik, there are a number of other fascist organisations, presenting themselves in the tradition of the “Arrow Cross” – the fascist organisation linked to Hitler’s Third Reich and responsible for the terror regime under the Nazi collaborator Szalsi.

All the right in Hungary play on the propaganda of “us Hungarians” against “the others” – Jews, Roma, homosexual. Although Jobbik is clearly neo-fascist, the Fidesz is more difficult to characterise. Even though Orbán is the vice-chairman of the “European People’s Party”, it is not a classic, west European ’conservative’ party. The Fidesz and Orbán hardly ever distance themselves from racist, anti-Semitic and fascist propaganda and activities. Indeed, Orban frequently uses rhetoric that would not only be acceptable to Jobbik, but even to the Arrow Cross. The media close to Orbán uses aggressive racist and anti-Semitic rhetoric. The chief editor of the “Magyar Demokrata” – Orbán’s favourite newspaper – has a son in the Hungarian Guard.

There are clearly links between Fidesz and Jobbik. On the one hand, many of Fidesz’s proposals are so right wing that Jobbik has no difficulty supporting them. On the other hand, Fidesz uses Jobbik as a pressure group, whilst worrying that it could go too far. In 2006, when the masses stormed the TV headquarters, Fidesz, at the beginning organised its supporters to come to Budapest to support the protest. But when the influence of organised fascists became more obvious and there was a danger the whole movement would get out of control, Fidesz moved away and focused on the upcoming elections. Clearly this is dangerous. When Fidesz comes under pressure and loses support because of its attacks on workers’ living standards, it could shift further to the right to prevent Jobbik taking over part of its vote base. Jobbik is already criticising Fidesz for not being more hard-line in order to gain from the growing disillusionment.

The way in which Fidesz operates is shown by the 2010 campaign of slander and intimidation against the liberal writer, Paul Lendvai and his new book, which is very critical about Jobbik and Fidesz. Campaigns were held against public meetings with the author in Switzerland and Germany and intimidation was used to force them to be cancelled. Whilst this demonstrates how Fidesz uses the methods of the far right, it also appears that official ’diplomatic’ pressure was used by Hungary to get the cancellation of another of his meetings planned to be held in the Austrian embassy in Germany.

The influence of racists and the far right in the state apparatus is already widespread. Far right and fascist demonstrations are held openly, whilst anti-fascist mobilisations are harassed by the police, who argue they cannot assure the safety of the anti-fascists. This is a reflection of the strong influence of the far right and fascists in the police. About 5,500 police staff (about ten per cent of the total) belong to a special Jobbik police organisation. The increasingly repressive approach by the state was also reflected in the banning of a planned demonstration by the residents of Kolontár to demand state assistance after losing everything in the toxic waste catastrophe.

The way the law is used against the Roma people is another indication of its racist nature. Paragraph 174/B of the criminal code is supposed to be used against those who carry out “violence against the community” and was originally planned as a law against racist attacks. The way it is used now, however, shows that there are no universal rights in a capitalist society; laws can be re-interpreted to serve any change in the balance of forces within society. Two weeks after the racist murders in Tatárszentgyörgy and following threats of more fascist attacks, the Roma in Miskolc, where they are a large minority organised self defence groups, mistakenly attacked a car of innocent people. Two of the passengers were hurt, although not seriously. Whilst the fascist thugs roam free without arrest, eleven Roma men were arrested and sentenced to a total of 41 years in prison on the charge of “racist motivated violence”.

Fidesz has consistently demonstrated its authoritarian nature. As soon as Orbán came to power for the first time in 1998, he made clear he found the restraints of bourgeois democracy annoying. He introduced changes to reduce the influence of parliament and, in 2010, changed the election law, making it much more difficult for smaller parties to stand. To have candidates in elections to Budapest council, now, a party has to collect 26,000 validated signatures within the short period of 15 days.

Fidesz is a one-man show led by Orbán. He has spent the last decade building a media empire, with his friends and supporters controlling a large part of the printed media as well as television and radio. This has led commentators to draw comparisons not only between the ideology and authoritarian styles of Orbán and Horthy, but also with Berlusconi, because of his control over the press.

The latest attack on the right of free speech, incorporated in the new media law, marks a qualitative change in Orbán’s far-reaching control over the media. A special agency for the de facto censorship of the media (NMHM) has been established with only Fidesz people on it. Fines up to €700,000 will help to keep down oppositional voices. Throughout the media there is a brutal purge taking place. Staff at all levels – from managers to cleaners – are being removed and replaced with Fidesz supporters. Connected with this is a new law that makes it easier to sack civil servants without reason.

There are strong elements of an authoritarian regime in Hungary. The process has not gone as far as that in the more eastern states of the former Soviet block, and it would be wrong to call Hungary a dictatorship at this stage. Even the Central Asian republics have to keep some semblance of elections and parliaments as a fig-leaf to disguise their authoritarian nature. But Hungary, as a member of the EU, still has to maintain key features of parliamentary democracies. It is open to question how much further authoritarianism could develop. Under the hammer-blows of new economic or social crises, the right wing may try to strengthen their rule, particularly in an attempt to stave off protests. But this increase in repressive measures could well provoke a backlash, with demonstrators not only calling for economic justice, but campaigning in defence of democratic rights too.

The Hungarian working class has not yet spoken

In April 2010, the Fidesz had a landslide election victory, gaining 2/3 of all parliamentary seats. This success is a result of the widespread disillusionment with the MSZP administration, and because of the lack of a left wing alternative. As in other countries, we see that the vote for far right or even fascist organisations does not merely reflect a rightward drift in society but is more the result of frustration and the wish for fundamental changes.

Fidesz got its large majority in seats with only slightly more than 50% of the votes. The turn-out was only 64%, meaning that less than a third of the population actually voted for them. This reflects the angry, but also confused, mood in society.

The illusions in capitalism felt by big sections of the population at the beginning of the 1990s have now disappeared. Three out of four youth in Hungary, for example, believe that there could be a new ‘system change’. They support the re-nationalisation of the most important companies and the call to make those responsible for the crisis pay.

But these ideas have no vehicle through which they can be expressed. Despite his nationalistic pseudo-anti-capitalist rhetoric, Orbán’s policies show he is clearly a 100% capitalist politician. His economic programme shows no fundamental break with the policy of the last governments, although he hides his neo-liberal agenda behind populist policies. At the moment he seems to be attempting to ignore the crisis, presenting a rosy perspective. Fidesz, for example, currently forecasts economic growth rates for Hungary at far higher levels than the EU and international institutions predict. Although such forecasts have been unreliable in the past period, it is obvious that Orbán is consciously overstating the potential for growth, and if anyone disputes his figures they are removed from his office and control bodies closed down.

At the beginning of 2011, when Hungary took over the EU presidency there was a wave of protest and criticism from different EU-states and governments against the new media law in Hungary. This law clearly severely restricts press freedom. Driving the apparent concern for democratic rights on the part of the EU (which ignores the issue in a number of other countries) is a deep worry about Hungary’s economic future, its stability and therefore the security of western investments. In particular they are concerned about the special “crisis” taxes levied on trade, telecommunications, energy and banking companies, mainly affecting foreign companies. (Orbán calls it the “new system”, as he argues that after 2011 there will be no crisis.) It is a populist measure, which will add more than 1% of GDP to 2011 budget revenues and is intended to demonstrate to the Hungarian population that he is standing up to “international capital”. This tax is quite small in reality and intended to divert attention away from the large cuts package now being implemented.

The sabre-rattling against the EU and the IMF accompanies widespread neo-liberal attacks on the public sector and working class people. These include plans for “structural reforms” (read: cuts) in the pension system, health, local authorities and public transport. The government argues that “taboos will have to be broken” (read: very hard attacks). The IMF delegation called the budget “bold but risky”. This is against the background of the number of people in jobs being on an historically low level. The income gap is widening and the newly introduced flat-rate tax only benefits the wealthy. 700,000 people are unable to pay their debts, and at the end of 2010 there was a further reduction in real income.

Changes in the constitution make it possible to introduce back-dated taxes in the future. Whilst there are noisy international protests at the “crisis tax” – there is no mention made of the new law that makes it possible to tax all public expenditure -pensions, wages in the public sector, social benefits… This is creating enormous insecurity for the working class. The government is currently trying to intimidate whole layers of the work force especially in the public sector to accept the taxes. (“If you protest, you will be taxed”.) But it is likely that at a certain stage these attacks will lead to social unrest and explosions.

Nor should other measures taken by Orbán, such as the re-nationalisation of the private pension system, be interpreted, as they sometimes are by western commentators, as “left”. There is nothing left or socialist in this measure, it is merely another attempt by the government to get its hands on the estimated €12 billion currently in the fund. This money – representing about 10% of total financial activity – will be incorporated into the budget and spent. Working class people to whom this money belongs were forced in 1997 to put their money into private pension funds. How or if the will get this money back in the form of pensions is questionable and can therefore be a focus for further protests.

Many of the measures proposed by Orbán that meet with the objections of western commentators represent no real break with pro-capitalist policies: the taxing of big and international companies and re-nationalisation are typical measures used by authoritarian capitalist regimes in periods of economic crisis. Although the CWI has no sympathy for Orbán, these measures look a bit like what a left, socialist government could do in the interests of the working class.

It is open at this point in time, how Hungary will develop. It is excluded that Orbán can solve the social problems. It is very unlikely that he will fulfil his promise of creating 400,000 new jobs in the next four years. The new flat-rate tax benefits only the richest 20% of society. Notwithstanding all his rhetoric against the IMF and the EU, Orbán will continue to pay back the loans and make the working class pay.

Whilst the working class is a force in society that has not yet entered onto the stage of struggle in this period, there are already signs that the Hungarian workers will soon join their comrades in other countries who are fighting against austerity measures being introduced by their governments. About 18% or the workforce are organised, most of the unions are still linked to the MZSP and have not organised any protests in the past period. But the strikes in public transport in Budapest at the beginning of 2010 and the threat of strikes on the railways later last year helped to demonstrate what workers can achieve if they take decisive action. The reduction of the school leaving age from 18 to 15 has already met with a sharp rebuke by the teachers’ union and protests by workers at the Dunaújváros factory of Hankook indicate that workers are beginning to lose their patience.

It should never be forgotten that the Hungarian working class has strong fighting, socialist and communist traditions. They include the Commune in 1919, the struggle against fascism in the period before the Stalinist takeover and the heroic uprising of the Hungarian working class in 1956 against Stalinism and for genuine socialism. These traditions even remain today to a certain degree in the consciousness of younger people. In the protests in 2006, which became dominated by the right wing, there were also frequent references to the anti-Stalinist workers’ revolution of 1956.

The main trade union federations in Hungary and the European Trade Union Congress are planning a demonstration against austerity policies on April 9 in Budapest to coincide with a meeting of the European finance ministers. If properly organised, this can play a big role in beginning to turn the tide against the reactionary policies of Fidesz and its neo-fascist allies. There should be no place for racist policies on this demonstration. To defeat the policies of austerity, it is necessary for a united struggle by all those who suffer from them. Unity is needed of Hungarian and Roma workers, youth and unemployed, in the fight for jobs, proper wages and pensions for all.

The call by the trade unions “for a more social Europe, fair wages and quality jobs” is of course an abstract demand; if it is to mean anything it needs to be made concrete. The CWI calls for the repeal of the flat rate tax and for the tax burden to be transferred to big business and the rich. Hungary should refuse to pay back the loans to the international financial institutions and banks and use the money saved to implement a programme of job creation, reverse the cuts in social expenditure and provide decent housing for all.

The potential for the development of a progressive left force was demonstrated by the appearance of the Greens’ ‘Politics Can Be Different’ party at the last election which gained 7.5% of the vote. The LMP, as well as the MSZP and the Liberals, take up issues like racism, attacks on democratic rights and the growth of the far right and, given the vacuum on the left, they could gain support on these issues. But they have no solution for tackling the root cause of these problems. Instead of proposing a programme to deal with unemployment, poor wages and declining social conditions, which the far right exploit to build their support, they propose to ban Jobbik and other far right groups.

It is therefore important that the left and working class movement places itself at the forefront of the fight against the attacks on democratic rights and the growth of the far right by linking these questions with the serious social problems that exist in the country and by presenting a genuinely democratic socialist alternative to the horrors created by the capitalist system.

It has, undoubtedly been difficult for genuine Marxists to work in Hungary in the past period. The brutal suppression of the 1956 revolution by the Stalinist tanks, the transition to capitalism led by the same bureaucrats who claimed to be communists and the corruption of the sharply pro-market so called “socialist” MSZP have caused much disorientation in the workers’ movement. The trade union movement too has to struggle to free itself from the shameful traditions of the phoney trade unions during the “soviet era”. These were not vehicles for the defence of workers’ rights but instruments used by the Stalinist state and factory management to neutralise any attempts at workers’ self-organisation.

Workers in the newly developing independent trade unions will soon find that their interests are also in conflict with those of the European Union trade union bureaucrats, who are closely tied to the social democratic parties; in many countries these parties have been implementing neo-liberal policies. A strong workers’ movement will develop in Hungary under the blow of events. It will succeed in effectively defending workers’ interests if it places at the centre of its demands opposition to all cuts in jobs, wages and budget expenditure.

Many liberals and lefts give up on Hungary as a lost cause, saying it has fallen to the far right. But the CWI does not agree with this. The most powerful force in Hungarian society – the working class – has not moved into action yet. It is inevitable that protests around different questions in the future – for democratic rights, against racism and anti-Semitism – will develop. Increasingly the working class will have no option but to organise against the attacks of Orbán on working class rights and living standards.

The need for an alternative to the new capitalist Hungary will be raised. Privatisation should be stopped and the key sectors of the economy and the banks taken back into state ownership. They should however not be run as before by a state bureaucracy, but, as the workers in 1956 demanded, under the control and management of elected workers’ committees. This would allow the economy to be planned in the interests of all. This process will undoubtedly take place in tandem with the moves in other EU countries to end capitalism, allowing for the establishment of a confederation of democratic socialist states of Europe.

Socialists have to prepare now for these battles, develop a programme and demands to give answers to the burning social questions that will undermine the basis of Jobbik, Fidesz and the others. The CWI is prepared to give all practical help possible in achieving this.

Special financial appeal to all readers of socialistworld.net |

Support building alternative socialist media Socialistworld.net provides a unique analysis and perspective of world events. Socialistworld.net also plays a crucial role in building the struggle for socialism across all continents. Capitalism has failed! Assist us to build the fight-back and prepare for the stormy period of class struggles ahead. Please make a donation to help us reach more readers and to widen our socialist campaigning work across the world. |

Donate via Paypal |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

Be the first to comment